- Probationary period is a structured trial to assess a recruit’s suitability, competence, and fitness before permanence.

- A probationer holds a transitory appointment with no substantive right until a specific confirmation order.

- Employers may extend probation per rules; employees cannot later challenge agreed probation terms or durations.

- Confirmation requires fair, rational exercise of discretion and procedural fairness, not arbitrary decisions.

- Deemed confirmation arises when rules fix a maximum probation and employer allows continued service beyond it without adverse order.

- Exceptions to deemed confirmation exist where service rules explicitly permit extension or contain overriding provisions.

- Confirmation grants substantive status and Article 311 protections; non-confirmation ends the appointment or reverts promotees to prior posts.

The Law of Probation in Government Service

1.0 Introduction: The Foundational Role of Probation in Public Service

The probationary period is a cornerstone of public service employment, serving a critical strategic function for both the government as an employer and the newly recruited employee. It is a structured, preliminary phase of appointment designed as a trial period. For the employer, this phase provides a vital opportunity—a locus poenitentiae (an opportunity to repent or change one’s mind)—to meticulously assess a new recruit’s suitability, competence, work ethic, and overall fitness for a permanent role before granting them a substantive post. For the employee, it is the pathway to securing a permanent position and the rights and protections that accompany it. This period, therefore, is not merely a formality but a determinative stage governed by a distinct and evolving body of legal principles.

2.0 The Probationary Appointment: Core Legal Principles

A probationary appointment is, by its very nature, an initial recruitment made on a trial basis for a specified period. This section deconstructs the legal character of this employment phase, focusing on its underlying purpose, the specific duration, and the limited legal rights afforded to the appointee before confirmation. The following principles, established through landmark judicial decisions, define the nature of a probationary appointment.

- Purpose of Probation: The primary rationale for probation is to enable the employer to guard against errors in judgment during the selection process. As explained by the Supreme Court in Ajit Singh v State of Punjab and Parshotam Lal Dhingra v UOI, the concept was devised to prevent an incompetent or inefficient servant from being permanently foisted upon the public service, especially as charges of inefficiency are easy to make but difficult to prove. It provides the employer with a period to observe the employee’s performance before making a long-term commitment. The court in Ajit Singh eloquently described this rationale:

- Legal Status of a Probationer: It is a settled principle of service law that a probationer holds a transitory appointment and possesses no substantive right to the post. Until an order of confirmation is issued, their right to continue in the position is not secure. Consequently, their services can be terminated at any time during the probationary period if they are found unsuitable, as established in foundational cases like Parshotam Lal Dhingra v UOI and affirmed in UOI v Raj Kumar Gupta.

- Period of Probation: The duration of the probationary period is typically stipulated in the relevant service rules or the individual’s order of appointment. An appointment made for a specific probationary period legally concludes by the efflux of time. An individual who accepts the terms of the appointment cannot later challenge those conditions. The rules may also permit extensions of this period, sometimes specifying a maximum duration, to allow the employer further time for assessment.

Understanding the transitory nature of the probationary appointment is essential to appreciating the significance of the next stage: the process of confirmation.

Contact & Consultation

Patra’s Law Chambers

Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

3.0 The Doctrine of Confirmation: From Probation to Permanence

Confirmation is the pivotal event that transforms a probationary appointment into a permanent and substantive one, granting the employee a right to the post. While the act of confirmation may seem straightforward, it is governed by a nuanced set of legal principles concerning the employer’s discretion, the necessity of procedural fairness, and the critical question of timing. This section examines the judicial evolution and current legal standards that regulate the confirmation process.

3.1 Discretion and Fairness in Confirmation

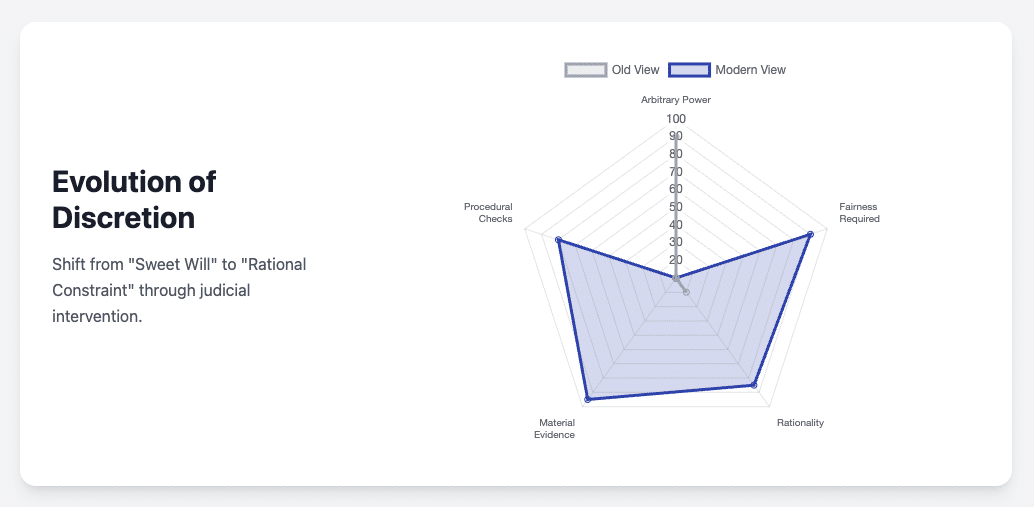

The scope of an employer’s discretion in confirming an employee has been a subject of significant judicial evolution, moving from a position of near-absolute authority to one constrained by principles of rationality and fairness.

- A historical perspective is found in SB Patwardhan v State of Maharashtra, where the Supreme Court famously described confirmation as one of the “inglorious uncertainties of Government service,” observing that it often depended on the “sweet will and pleasure of the Government” rather than objective criteria.

- This aphorism, however, was later “explained, distinguished and severely restricted in operation” by the Court in K Thimappa v Chairman, Central Board of Directors, SBI. The Court clarified that the Patwardhan dicta primarily applied in contexts where the rule of seniority was linked to the date of confirmation, a practice that created uncertainty. The Thimappa decision narrowed the application of the “sweet will” doctrine, signaling a move towards a more structured and rational basis for confirmation decisions.

- The modern legal position is that while the employer retains a large area of discretion, this power is not absolute and must be exercised fairly and rationally. In Syed Azam Hussaini v Andhra Bank Ltd, it was held that terminating a probationer’s services without any material evidence of unsatisfactory work is unreasonable and illegal. The decision not to confirm cannot be an arbitrary or irrational one.

- A crucial precondition for confirmation is the validity of the initial appointment itself. As established in Ashwani Kumar v State of Bihar, the question of confirmation can only arise if the employee’s initial recruitment was made against a properly sanctioned vacancy.

3.2 The Confirmation Process

The process leading to a confirmation decision must adhere to principles of fairness and be based on a legitimate assessment of the employee’s performance.

- The Supreme Court’s observations in Sumat P Shere v UOI, though made in the context of an ad-hoc employee, are highly relevant. The Court emphasized the moral and legal obligation of the employer to act fairly. This includes communicating any defects in performance to the employee and providing them an opportunity to improve. As the Court noted, “Timely communication of the assessment of work in such cases may put the employee on the right track.” A failure to provide such constructive feedback may render a subsequent decision of unsuitability arbitrary.

- While fairness is paramount, courts generally do not substitute their own judgment for that of the employer. If the employer’s assessment of unsatisfactory performance is supported by some material on record, a court will not typically interfere with that decision, as noted in Secy., Technical Education, UP v Lalit Mohan Upadhyay.

- In the specific context of the judiciary, the High Court has a unique and “solemn duty” to meticulously scrutinize the service records of judicial officers before confirmation to ensure their honesty and integrity, a principle laid down in Rajesh Kohli v High Court of Jammu and Kashmir.

3.3 The Necessity of a Specific Confirmation Order

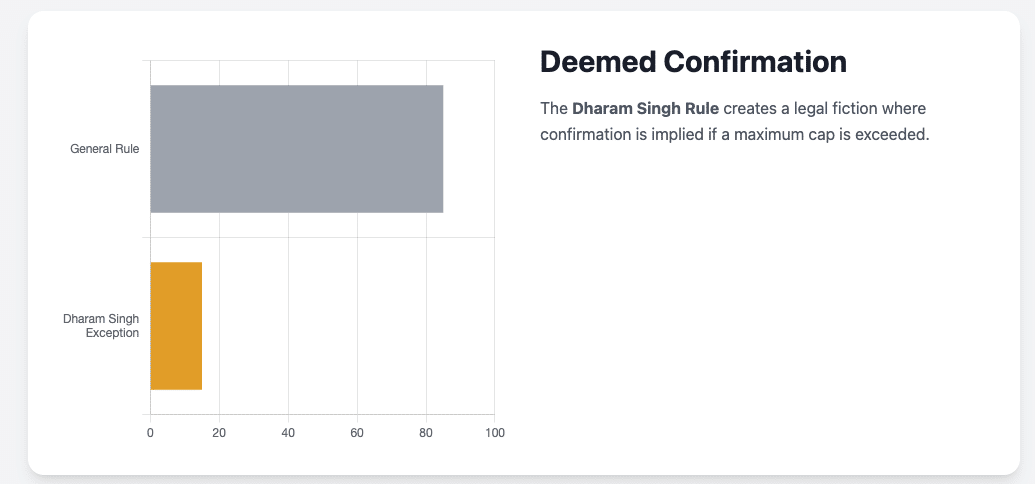

The general and firmly established rule is that confirmation is not an automatic process. The expiry of the probationary period, even if the employee is allowed to continue working, does not in itself confer permanent status.

- This principle was definitively settled by a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Sukhbans Singh v State of Punjab, which held:

This clear rule, however, is subject to a critical and complex exception known as the doctrine of deemed confirmation.

4.0 The Doctrine of Deemed Confirmation: A Critical Exception

The doctrine of “deemed” or “implied” confirmation addresses situations where an employee continues to serve beyond the prescribed probationary period without any formal order of confirmation or termination. Its application is not universal and depends entirely on the specific language of the governing service rules. As analyzed by M. Jagannadha Rao, J., judicial interpretation has crystallized into two distinct approaches based on the structure of these rules.

| Judicial Principle | Governing Conditions and Key Case Law |

| No Implied Confirmation (General Rule) | If service rules specify a probation period but are silent on a maximum limit, or simply allow for extensions without a cap, continuing service past the initial period does not amount to automatic confirmation. The employee is considered to be on probation until a specific order is issued. This principle was established in Sukhbans Singh v State of Punjab and State of UP v Akbar Ali Khan. Furthermore, if the rules require the competent authority to issue a certificate of satisfactory completion of probation, confirmation is not automatic, as held in Commissioner of Police Hubli v RS More. |

| Deemed Confirmation by Implication (The Dharam Singh Rule) | If the service rules explicitly prescribe a maximum period of probation beyond which it cannot be extended, and the employer allows the employee to continue working after this maximum period has expired without issuing an adverse order, the employee is considered “deemed confirmed.” The reasoning, as laid down by the Constitution Bench in State of Punjab v Dharam Singh, is that the rule itself forbids any further extension, thus creating a legal fiction of confirmation by implication. This principle is distinct from cases where no maximum period is specified in the rules. |

Important Nuances and Exceptions

The application of these principles is subject to further qualifications:

- Overriding Rules: Even where a maximum probationary period exists, the principle from Dharam Singh can be negated by other specific provisions in the service rules. For example, in Shamsher Singh v State of Punjab, an “explanation” attached to the relevant rule stipulated that “the period of probation shall be deemed extended if a subordinate Judge is not confirmed on the expiry of his period of probation.” This specific provision effectively overrode the general principle of deemed confirmation.

- Employee Conduct: Deemed confirmation requires a positive act by the employer of allowing the employee to continue working. If the employee’s own actions, such as being absent from duty for a long period, prevent the employer from making a timely decision, no inference of implied confirmation can be drawn (Chief GM, State Bank of India v Bijoy Kumar Mishra).

- Unsatisfactory Performance: If an employee is given an opportunity to improve beyond the maximum period of probation but fails to do so, the principle of deemed confirmation will not apply. The extension is seen as a grace period for improvement, not a prelude to automatic confirmation (Jai Kishan v Commissioner of Police).

The complexities surrounding confirmation and non-confirmation lead to distinct legal consequences that define an employee’s career trajectory.

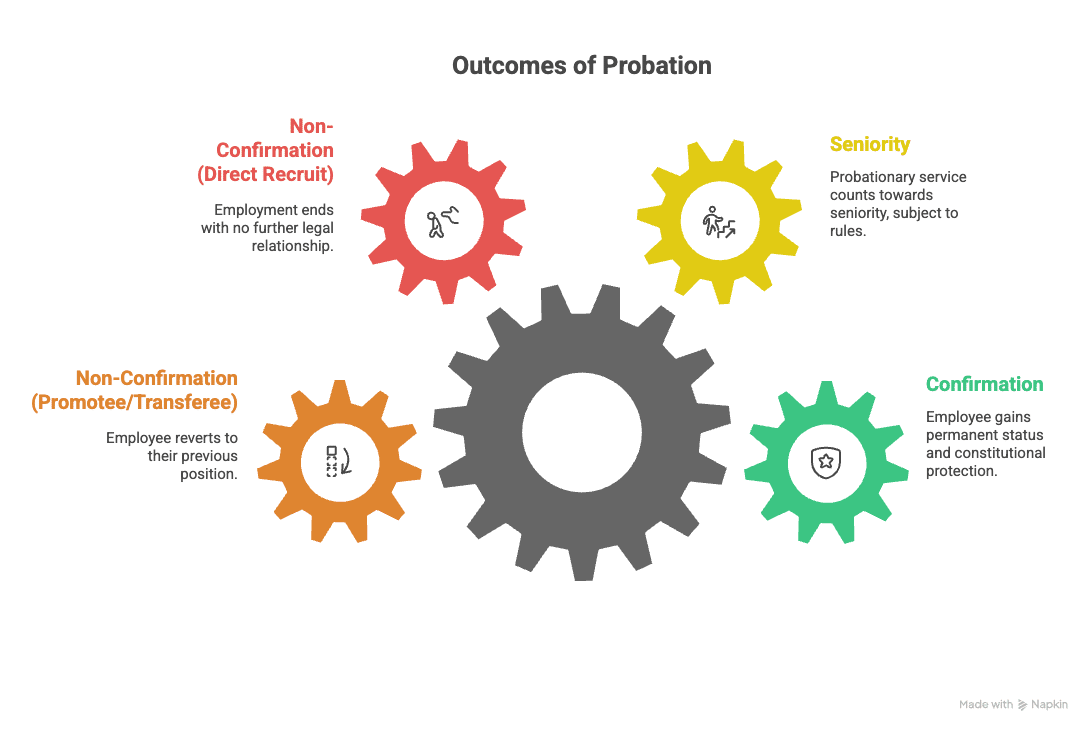

5.0 Consequences of Confirmation and Non-Confirmation

The outcome of the probationary period carries profound and distinct consequences for an employee’s service career, legal rights, and available remedies. Whether an individual is confirmed or not determines their status, security of tenure, and the procedures required for any subsequent disciplinary action.

- Consequence of Confirmation: Upon confirmation, an employee attains a substantive right to hold the post. Their service becomes permanent, and they can only be terminated in accordance with constitutionally valid rules. For a civil servant, any punitive action such as dismissal or removal from service would necessitate full compliance with the procedural safeguards guaranteed under Article 311 of the Constitution. For other public servants not covered by Article 311, the position is substantially the same, requiring termination to be in accordance with their conditions of service.

- Confirmation and Seniority: Generally, the period of service rendered as a probationer is not disregarded when determining an employee’s seniority. However, the specific service rules governing seniority are paramount in making this determination (SB Patwardhan v State of Maharashtra).

- Consequence of Non-Confirmation (Direct Recruit): If a direct recruit is found to be unsuitable at the end of the probationary period (or its extension), the probationary appointment simply comes to an end, and the jural (legal) relationship between the employer and employee ceases to exist.

- Consequence of Non-Confirmation (Promotee/Transferee): For an employee appointed on probation through promotion or transfer, non-confirmation in the higher post does not typically result in termination of employment. Instead, the employee is reverted to the lower post from which they were promoted or transferred.

Understanding these divergent outcomes is crucial for appreciating the high stakes involved in the probationary process for both the employee and the employer.

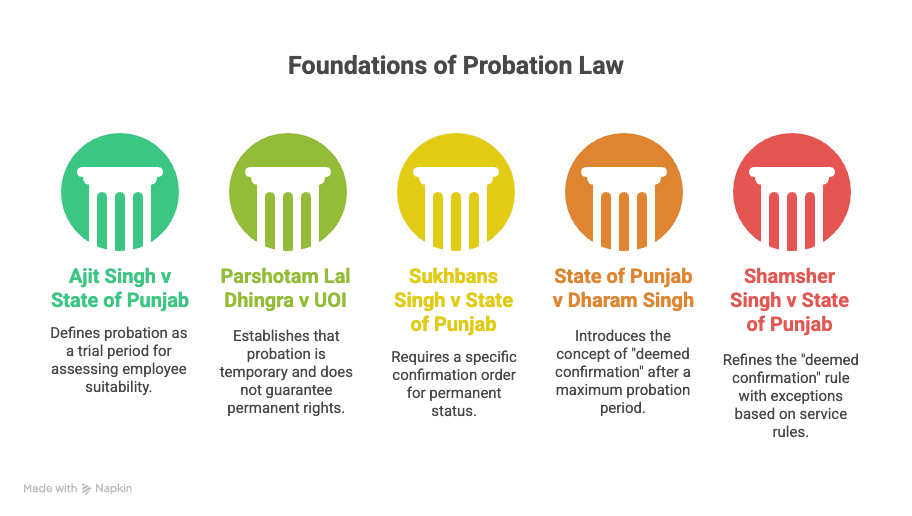

6.0 Key Case Law Summary

This section provides a consolidated summary of the landmark Supreme Court cases that have shaped the law of probation in India, focusing on the core legal principles established by each.

| Case Name | Core Legal Principle Established |

| Ajit Singh v State of Punjab | Articulated the core concept and purpose of probation as a trial period for the employer to assess the suitability, efficiency, and competence of a new recruit before absorption into service. |

| Parshotam Lal Dhingra v UOI | A foundational case establishing that a probationary appointment is temporary and does not grant the employee a substantive right to the post until confirmation. |

| Sukhbans Singh v State of Punjab | Laid down the general rule that a probationer does not automatically acquire permanent status after the expiry of the probationary period. A specific order of confirmation is necessary unless rules expressly provide otherwise. |

| State of Punjab v Dharam Singh | Established the crucial exception of “deemed confirmation.” If service rules fix a maximum period for probation that cannot be extended, an employee who continues in the post beyond that maximum period is deemed to have been confirmed by implication. |

| Shamsher Singh v State of Punjab | Refined the Dharam Singh rule by showing that it can be negated by other specific provisions in the service rules. In this case, an “explanation” to the rule allowed the probationary period to continue even beyond the stated maximum limit. |

In conclusion, the legal status of a probationer is fundamentally defined by the specific service rules governing their appointment. The judiciary, through decades of interpretation, has provided crucial clarity on the limits of employer discretion, the requirements of procedural fairness, and the specific conditions under which confirmation can be implied. This framework balances the employer’s need to ensure a competent workforce with the employee’s right to fair and non-arbitrary treatment.

Contact & Consultation

Patra’s Law Chambers

Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044