Key takeaways

- Seniority is essential in government service, significantly impacting promotions, assignments, pay scales, and pensions.

- Recognized as a valuable civil right, seniority is not a fundamental right but is protected by constitutional provisions.

- Determining seniority involves strict adherence to rules, focusing primarily on the length of service in a specific cadre.

- Legal disputes often arise over inter-se seniority between direct recruits and promotees, significantly influenced by recent Supreme Court rulings.

- Challenging a seniority list requires prompt action; delays may jeopardize an employee's case due to strict judicial timelines.

Navigating the Maze of Seniority: A Complete Guide to Service Law in India

YouTube video link:

Introduction: Why Seniority is More Than Just a Number in Government Service

For a government servant, a position on a list is far more than a mere number. It is a marker that dictates the entire trajectory of a career—promotions, assignments, pay scales, and ultimately, the quantum of pension. This marker is seniority, a concept that, while seemingly straightforward, is governed by a complex and ever-evolving web of rules, administrative instructions, and a vast body of case law meticulously developed over decades by the Supreme Court of India and various High Courts. An employee’s understanding of this concept, and the rights attached to it, can be the single most crucial factor in ensuring fair career progression.

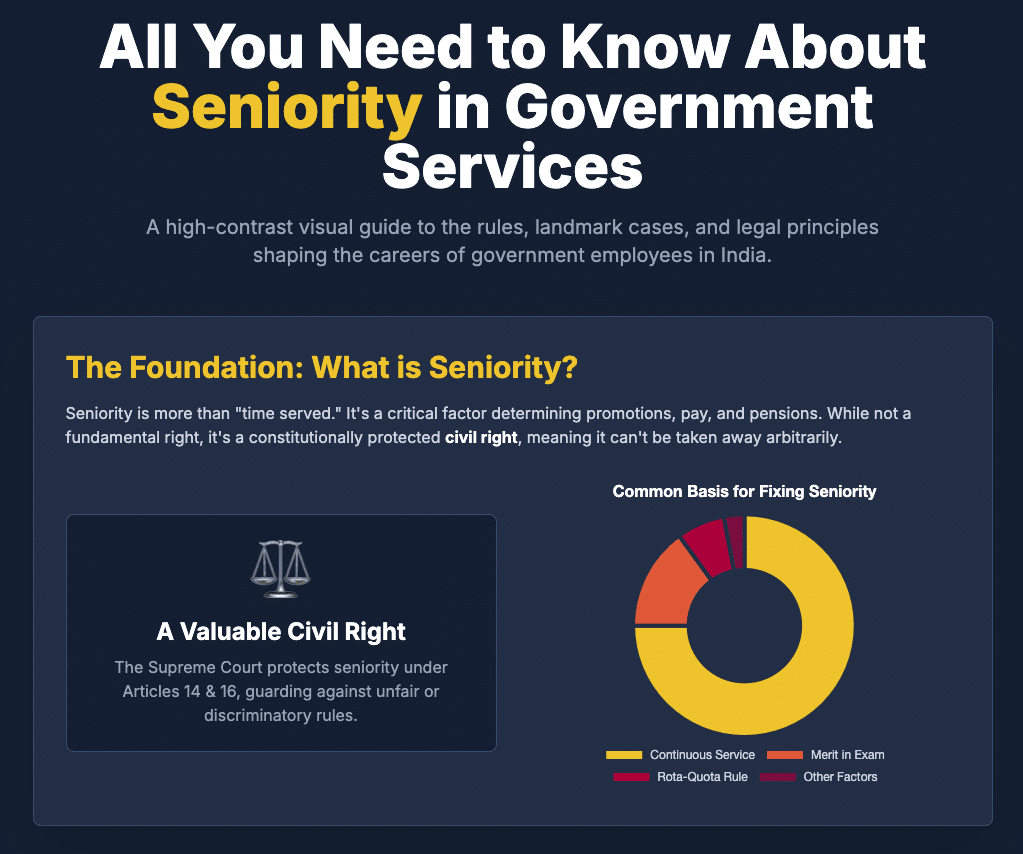

In the eyes of the law, seniority is not just an administrative convenience; it is recognized as a “valuable civil right”.1 This status grants it significant protection, even though it is not a fundamental right. The infringement of this right can have profound consequences, potentially stalling a deserving employee’s career while others, who may be junior, move ahead. The primary objective of the seniority system is to establish a fair, transparent, and orderly process for filling promotional posts, thereby maintaining morale and efficiency within the services.1

This article aims to demystify the intricate law of seniority in Indian government services. It serves as a comprehensive guide, navigating from the foundational legal principles to the most contentious and heavily litigated disputes. By breaking down the governing rules, methods of calculation, and the legal recourse available, this guide will empower every government employee to understand their position, protect their rights, and seek expert legal counsel when those rights are jeopardized.

Section 1: The Bedrock of Seniority — Core Legal Principles

What is Seniority in the Eyes of the Law?

At its core, seniority in service jurisprudence simply means the “length of service”.1 It signifies the precedence or preferential position an employee holds over others in similar circumstances within the same grade or cadre.1 The Supreme Court of India has consistently held that the principal purpose of assigning seniority is to create a structured and predictable framework for promotions. While other factors like merit can be incorporated, seniority is rarely, if ever, completely disregarded. Even in promotion systems based on “selection,” seniority in the feeder grade is crucial as it determines the “zone of consideration”—the pool of eligible candidates from which the selection is made.1

Is Seniority a Fundamental Right? Understanding Your Civil Right and Its Constitutional Protections

A critical legal distinction that every government employee must understand is that seniority is not a fundamental right enshrined in Part III of the Constitution. Instead, the judiciary has classified it as a “valuable civil right”.1 The practical implication of this is significant. Because it is not a fundamental right, the conditions of service, including the principles of seniority, can be altered by the government through the framing of valid rules. An employee cannot claim an absolute, unchangeable right to a particular seniority position.

However, this does not leave the employee without protection. The legal framework is built on a delicate balance between the government’s power to regulate service conditions and the individual’s right to fair treatment. This is where the Constitution steps in. Any rule or administrative action that arbitrarily or irrationally destroys an employee’s seniority can be challenged and struck down by the courts for violating Article 14 (Right to Equality) and Article 16 (Equality of Opportunity in Matters of Public Employment).1 Therefore, while the government sets the rules of the game, the judiciary acts as a referee, ensuring those rules are fair, non-discriminatory, and applied consistently to all employees within the same class. A legal challenge to a seniority rule is not about whether an employee personally agrees with it, but whether the rule itself is constitutionally sound.

Seniority vs. Rank vs. Penalties: Distinguishing Key Service Concepts

The term “seniority” is often used interchangeably with other service concepts, leading to confusion. The law, however, makes clear distinctions:

● Seniority vs. Rank: Losing a few places in a seniority list is not a “reduction in rank” as contemplated under Article 311(2) of the Constitution, which provides protections against dismissal, removal, or reduction in rank. “Rank” refers to an employee’s classification within the service (e.g., Assistant Engineer, Executive Engineer), whereas “seniority” refers to their specific place within the list of all employees holding that same rank or classification.1

● Seniority vs. Penalties: A disciplinary penalty for misconduct, such as the “stoppage of increment,” is entirely separate from an employee’s seniority. The Supreme Court has unequivocally held that if an employee’s annual increment is withheld for a year as a punishment, this action should have no effect whatsoever on their position in the seniority list. To penalize an employee by stopping an increment and then also lowering their seniority for the same offense would amount to “double jeopardy”—punishing them twice for the same misconduct—which is legally impermissible.1 This is a vital protection against the imposition of disproportionate and multiple punishments for a single act.

Section 2: The Rulebook — The Governing Framework for Seniority

The determination of seniority is not an arbitrary exercise but is governed by a strict hierarchy of legal authority. Understanding this hierarchy is the first step in assessing the correctness of any seniority list.

The Hierarchy of Authority: Statutory Rules, Executive Orders, and Court Judgments

The legal framework for seniority fixation follows a clear pecking order 1:

1. Statutory Provisions Have Primacy: At the apex are statutory rules. These include Acts passed by the legislature and, most commonly, service rules framed by the executive under the power granted by Article 309 of the Constitution. Where such statutory rules exist, they are supreme. Any administrative or executive instruction that contradicts a statutory rule is ineffective and invalid.1 An employee has a vested right to have their seniority determined strictly in accordance with the rules that were in force at the time they were “borne in the cadre” (i.e., when they officially joined the service or grade).1

2. Retrospective Amendment of Rules: The government does have the power to amend service rules with retrospective effect. However, this power is not absolute. Courts generally “frown upon” retrospective amendments that take away the vested rights of employees, such as promotions already earned or seniority already settled under the old rules. For a retrospective amendment to be valid, it must be constitutionally sound and often includes a “saving clause” to protect actions already taken under the previous rules.1

3. Relaxation of Rules: Many service rules contain a provision that empowers the government to relax any rule in cases of undue hardship or for reasons of administrative exigency. This power of relaxation is considered valid as it is a creation of the rules themselves and can, in certain circumstances, be exercised with retrospective effect.1

When Rules are Absent: The Power of Executive Action and Judicially Evolved Principles

In many instances, statutory rules may be silent on the specific method of fixing seniority. In such a vacuum, the hierarchy of authority is as follows:

● Executive Orders: The government is entitled to fill the gap by issuing executive orders or administrative instructions. These orders will govern the field until statutory rules are framed.1 However, a critical limitation remains: these executive instructions

cannot override or conflict with any existing statutory rule on a related subject. For example, if a statutory rule states that seniority will be based on the date of appointment, an executive instruction cannot introduce a new criterion like giving weightage for past service.1

cannot override or conflict with any existing statutory rule on a related subject. For example, if a statutory rule states that seniority will be based on the date of appointment, an executive instruction cannot introduce a new criterion like giving weightage for past service.1

● Judicially Evolved Principles: If there are neither statutory rules nor executive instructions governing seniority, the courts will intervene to evolve a “fair and just principle”.1 In the overwhelming majority of such cases, the principle that the courts have universally applied is the length of continuous service in the grade or cadre.

The Validity Test: How Seniority Rules are Scrutinized for Fairness and Constitutionality

Every rule, whether statutory or executive, must withstand judicial scrutiny and be constitutionally valid. The primary test is against the principles of equality enshrined in Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution.1 When a seniority rule is challenged, the court’s inquiry is focused on one central question: is the rule

“arbitrary and irrational” to the extent that it creates inequality of opportunity among employees who belong to the same class?.1

The courts have clarified that they do not expect “mathematical precision” in the framing of such rules. The fairness of a rule is not judged by its adverse impact on a single individual’s career but by taking an “overall view” of its effect on the cadre as a whole. A rule will not be struck down simply because a court feels another rule might have been better or more appropriate; it will only be invalidated if it is found to be manifestly arbitrary or discriminatory.1

Section 3: The Golden Rule — Calculating Length of Service

#image_title

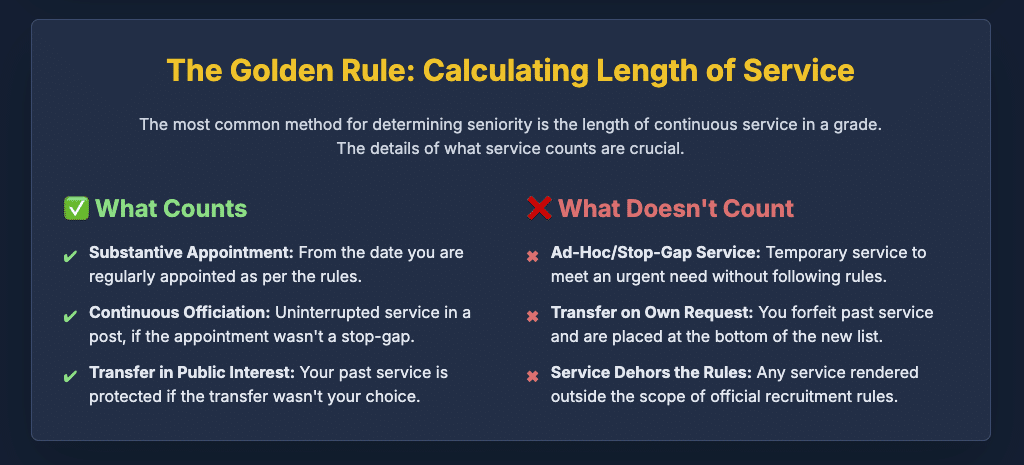

While various principles can be adopted, the “length of service rendered by an employee in a particular grade or cadre is the generally accepted determinative factor” for fixing seniority.1 This principle, often referred to as the rule of continuous officiation, is considered the most fair and reliable yardstick of experience.

The General Principle: Continuous Service in the Same Cadre

The foundational principle is that seniority is a comparative concept that applies only among employees who are similarly situated. Therefore, for the length of service to be counted, it must have been rendered in the same grade or cadre.1 A “cadre” is legally defined as the strength of a service or a part of a service sanctioned as a separate unit, including permanent and temporary posts.1 An employee cannot, for instance, claim seniority in the cadre of Executive Engineers based on their service rendered in the lower cadre of Assistant Engineers.

What Service Counts Towards Your Seniority?

Determining the exact start and end dates for calculating the length of service is often the crux of a seniority dispute. The judiciary has clarified what periods of service are generally included:

● Date of Substantive Appointment: The normal starting point for computing service is the date of substantive appointment, which is the date an employee regularly enters the service or cadre according to the rules. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that an employee cannot be granted seniority from a date prior to their “birth” in the cadre, as this would unfairly prejudice those who were already in the service.1

● Continuous Officiation: In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court recognized that there is no real difference between a substantive appointment and a long period of continuous officiating service. Seniority is a “manifestation of official experience,” and therefore, actual service rendered, whether officiating or substantive, is the primary yardstick. As long as the initial appointment was made according to rules and was not a stop-gap arrangement, the entire period of continuous service is counted.1

● Probation Period: The period an employee spends on probation or in training is fully reckoned for the purpose of seniority. Confirmation after successful completion of probation is not a fresh appointment; it is merely the confirmation of an appointment that was already made. The service is considered to have started from the date of initial probationary appointment.1

● Deputation: When an employee is sent on deputation to another department, their satisfactory service in the new post is deemed to have been rendered in their parent department for the purpose of seniority and promotion.1 However, if a deputationist later opts for permanent absorption in the new department, they generally cannot claim seniority for their deputation period over those already permanently serving in that department.1

● Transfer in Public Interest: If an employee is transferred from one cadre to another equivalent cadre for reasons of administrative efficiency or public interest (and not at their own request), they cannot be made to forfeit the benefit of the service rendered in their previous cadre. That service will be counted for seniority in the new cadre.1

What Service Does NOT Count? Common Pitfalls and Exclusions

Equally important is understanding what periods of service are typically excluded from seniority calculations. Employees must be wary of these common pitfalls:

● Service Dehors the Rules: Any service rendered “de hors” (outside) the recruitment rules is not counted. This includes service in an ex-cadre post (a post created for a special task outside the sanctioned cadre), service in a work-charged establishment (tied to a specific project), or service rendered on the basis of an invalid promotion that is later set aside.1

● Transfer on Request: This is one of the most critical and often misunderstood rules. If an employee seeks a transfer to another cadre or unit on their own request, they forfeit their past service for the purpose of seniority. They are treated as a new entrant in the new cadre and are placed at the bottom of the seniority list below all existing employees of that grade.1

● Resignation and Reinstatement: An employee who resigns from service and is later reinstated, for any reason, loses their original seniority entirely. Upon reinstatement, they are ranked junior to the last person on the seniority list as on that date.1

● Break in Service: If an employee leaves their service to take up a job in another organization and then rejoins the original service, this constitutes a “break in service.” Their seniority will be reckoned only from the date of their rejoining, and the previous spell of service will not be counted.1

The Ad-Hoc Service Conundrum: A Deep Dive into a Contentious Issue

Perhaps the single most litigated area in service law is the question of whether service rendered on an “ad-hoc” basis counts towards seniority. The general rule, stated repeatedly by the courts, is that ad-hoc, stop-gap, or fortuitous service does not count.1 Such appointments are made as a temporary measure to meet an urgent need, without following the regular selection process, and confer no right to seniority.

However, the judiciary has recognized that a blanket application of this rule can lead to grave injustice, especially when administrative lethargy is the cause of long periods of ad-hoc service. The Supreme Court has adopted a pragmatic “substance over form” approach, looking beyond the “ad-hoc” label to the actual nature of the appointment. The landmark Constitution Bench judgment in Direct Recruit Class II Engineering Officers’ Association v. State of Maharashtra laid down two crucial propositions that now govern this field 1:

● Proposition (A): If an initial appointment is made purely on an ad-hoc basis as a stop-gap measure and is not in accordance with the recruitment rules, the officiating service rendered in that post cannot be counted for seniority.

● Proposition (B): If the initial appointment, though not strictly in accordance with the rules, is not a fortuitous or stop-gap arrangement, and the employee continues in the post uninterruptedly until their service is regularized, the period of officiating service shall be counted for seniority.

This nuanced approach demonstrates that when long periods of ad-hoc service are a result of the government’s own failure to make regular appointments in a timely manner, the courts are reluctant to penalize the employee. Recent judgments, such as in P. Rammohan Rao v. K. Srinivas, have reinforced this principle, clarifying that if an appointment was made against a sanctioned post and continued for years until regularization, it cannot be treated as a mere stop-gap arrangement, and the pre-regularization service should be counted.4 The key takeaway is that the label “ad-hoc” is not the final word; the underlying facts and the continuous nature of the appointment are what truly matter.

Section 4: Beyond Length of Service — Alternative Methods of Fixing Seniority

While length of continuous service is the default and most common principle, it is not the only one. Service rules can validly prescribe other methods for determining seniority, provided they are fair, rational, and non-discriminatory.1

When Two Streams Meet: The Rota-Quota Rule for Direct Recruits and Promotees

A common scenario in government services is recruitment to a single cadre from two different sources: direct recruitment (through competitive examination) and promotion (from a lower cadre). To ensure fairness and balance between these two streams, service rules often prescribe a Quota-Roster (Rota) system.1

● The Quota Rule: This rule fixes a percentage or ratio of vacancies in a cadre to be filled from each source. For example, a rule might state that 50% of posts will be filled by direct recruitment and 50% by promotion.1

● The Rota (Rotational) Rule: This rule determines the placement of individuals from the two sources on the seniority list. It prescribes a roster or a cycle for arranging the appointees. For example, a 1:1 rota would mean the seniority list is prepared by placing one promotee, followed by one direct recruit, and so on.1

Where such a Rota-Quota rule exists in the statutory regulations, its application is mandatory. A seniority list prepared in violation of the prescribed quota and rota is illegal and liable to be struck down.1 However, the Supreme Court has also recognized a situation known as the

“breakdown” of the quota rule. If, over a continuous period of many years, the government fails to adhere to the quota (e.g., no direct recruits are appointed for a decade, and all posts are filled by promotion), an irresistible inference may be drawn that the rule has broken down. In such exceptional cases, the court may direct that seniority be fixed based on the length of continuous officiation, ignoring the broken-down quota.1

Merit as the Deciding Factor: Seniority from Examinations and Selections

Service rules can legitimately provide that for candidates recruited through a single competitive examination or selection process, their inter se seniority will be determined not by their date of joining but by their merit or rank in that examination.1 In such cases, a candidate who ranked higher in the merit list will be senior to a candidate who ranked lower, even if the lower-ranked candidate managed to join the service earlier.

This also brings into play the concepts of “seniority-cum-merit” and “merit-cum-seniority” for promotions 1:

● Seniority-cum-merit: Here, seniority is the primary consideration. Among all candidates who meet the minimum merit threshold, the senior-most will be promoted.

● Merit-cum-seniority: Here, merit is the primary consideration. The promotion is made by selecting the most meritorious candidate, with seniority being a consideration only when the merit of two or more candidates is equal.

Other Considerations: Weightage, Qualifications, and Salary

While less common, rules can also incorporate other rational principles for seniority fixation:

● Weightage: The government can give “weightage” or additional credit for past service to a particular category of employees if there is a rational basis for doing so, such as possessing special qualifications or valuable experience.1

● Date of Acquisition of Qualification: In some services, seniority may be reckoned from the date an employee acquires the essential qualification required for entry into that cadre.1

● Quantum of Salary: In very rare and extraordinary circumstances, such as the mass integration of services after the partition of India, the Supreme Court has upheld the quantum of salary drawn in the previous post as a valid basis for fixing seniority where comparing length of service was not feasible.1

Section 5: The Battlegrounds — Resolving Complex and Contentious Seniority Disputes

Certain areas of seniority law are perennial battlegrounds, leading to protracted litigation that can span decades. Understanding the judicial principles evolved to resolve these disputes is crucial for any government servant whose rights are affected.

Direct Recruits vs. Promotees: The Shifting Sands of Inter-Se Seniority

The conflict over inter-se seniority between direct recruits and promotees is one of the most enduring in service jurisprudence. The dispute typically arises because the direct recruitment process, involving public advertisement and examinations, is lengthy. In the interim, vacancies are often filled by promoting employees from a lower grade, sometimes on an ad-hoc basis. When the direct recruits are finally appointed, the promotees are already in place, leading to a clash over who should be considered senior.

The law in this area has seen a monumental shift. For years, the guiding principle, laid down by the Supreme Court in N.R. Parmar v. UOI (2012), was that seniority could be claimed from the date a vacancy arose (the “vacancy year”), even if the actual appointment happened much later.5 This rule greatly benefited direct recruits, as they could claim seniority from the year their vacancy was earmarked, effectively “jumping the queue” over promotees who were appointed in the interim. This principle, however, created significant administrative anomalies and was seen as unjust, as it allowed a person who was not even a member of the service to be declared senior to someone who was already working in the post.

Recognizing this flaw, the Supreme Court, in its landmark 2019 judgment in K. Meghachandra Singh v. Ningam Siro, explicitly overruled the N.R. Parmar decision.7 The Court held that the

N.R. Parmar ruling was incorrect and that seniority cannot be claimed from a date before an employee is even “born in the cadre.” The law as it stands today is clear: seniority can only be reckoned from the date of an employee’s substantive appointment to the post. The year in which the vacancy arose is irrelevant. This is a fundamental change that has restored the principle that seniority is a function of actual service rendered, not a hypothetical entitlement based on a vacancy.

Reservation and “Consequential Seniority”: A Constitutional Tug-of-War

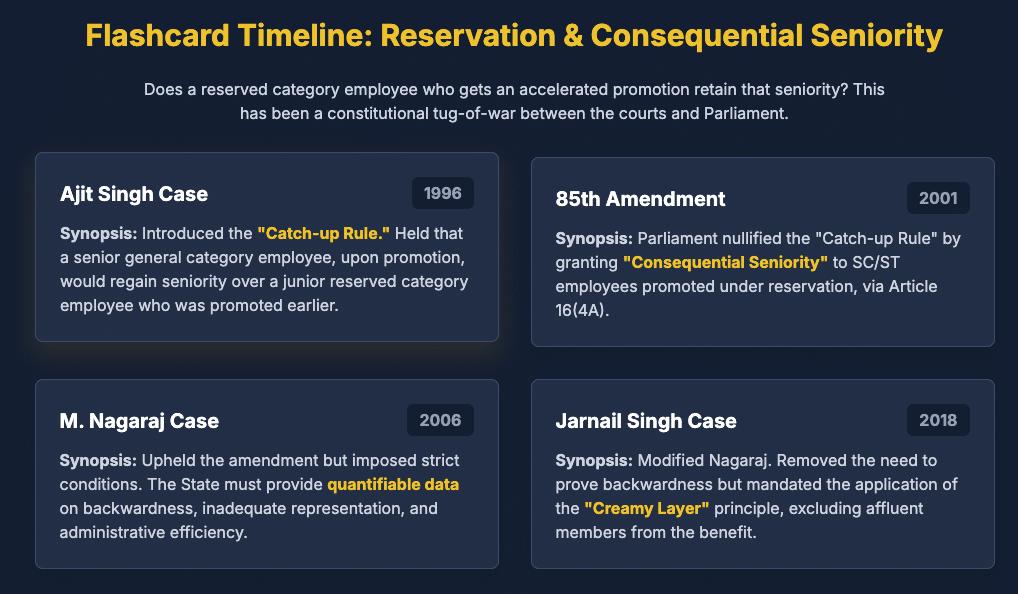

The interplay between reservation in promotion and seniority has been the subject of a constitutional tug-of-war between the judiciary and the Parliament. The issue revolves around “consequential seniority”—whether a reserved category (SC/ST) candidate who gets an accelerated promotion over a senior general category candidate due to reservation should retain that seniority in the promoted cadre.

The legal history has unfolded in several stages:

1. The “Catch-up Rule”: The Supreme Court, in Ajit Singh v. State of Punjab (1996), introduced the “catch-up rule.” It held that while reservation in promotion was permissible, it did not confer consequential seniority. This meant that when the senior general category candidate was eventually promoted, they would regain their original seniority over the junior reserved category candidate who had been promoted earlier.1

2. Parliament’s Response (85th Amendment): To nullify the “catch-up rule,” Parliament enacted the Constitution (85th Amendment) Act, 2001. This amendment inserted a clause in Article 16(4A) to explicitly provide for “consequential seniority” to SC/ST candidates promoted through reservation.8

3. The Nagaraj Conditions: The constitutional validity of this amendment was challenged. In M. Nagaraj v. UOI (2006), the Supreme Court upheld the amendment but imposed three stringent conditions on the State before it could grant consequential seniority. The State must collect quantifiable data to demonstrate: (i) the backwardness of the class, (ii) their inadequate representation in public employment, and (iii) that reservation would not compromise overall administrative efficiency.8

4. The Jarnail Singh Modification: These conditions made it very difficult for governments to implement consequential seniority. In Jarnail Singh v. Lacchmi Narain Gupta (2018), the Court modified the Nagaraj judgment. It held that since SCs and STs are presumed to be backward, the State is no longer required to collect data on their backwardness. However, the Court introduced a new condition: the State must apply the “creamy layer” principle and exclude the advanced members of the SC/ST communities from the benefit of reservation in promotion.8

5. Practical Application (B.K. Pavitra): The current legal framework requires the State to provide data on inadequate representation and administrative efficiency, while applying the creamy layer test. The case of B.K. Pavitra v. UOI-II (2019) serves as a practical example, where the Supreme Court upheld Karnataka’s consequential seniority law after the state government produced a detailed committee report with the necessary data to satisfy the judicial tests.12

When Cadres Merge: The Principles of Integration

When two or more government departments or cadres are merged into a single entity, the employer has the right to frame a new, rational principle to determine the inter se seniority of the employees in the newly integrated cadre.1 This is a policy matter for the executive. The principle adopted must be fair, just, and non-arbitrary. Courts will not interfere just because some employees face hardship, but they will strike down a principle that is irrational or discriminatory. The factors often considered in such integration are the length of service in the erstwhile cadres, the pay scales of the posts, and the nature and duties of the roles being merged.1

|

Case Name

|

Year

|

Core Principle Established

|

Relevance

|

|

Direct Recruit Class II Engg. Officers’ Assn. v. State of Maharashtra

|

1990

|

Established that continuous officiating service counts for seniority if the appointment was not stop-gap, but ad-hoc service does not.

|

Foundational case for determining when ad-hoc/officiating service is counted. 1

|

|

Ajit Singh v. State of Punjab (Ajit Singh-I & II)

|

1996/1999

|

Introduced the “catch-up rule” and later affirmed that reservation grants accelerated promotion but not consequential seniority.

|

Key precedent (though later amended by Constitution) establishing the rights of general category seniors vis-à-vis roster-point promotees. 1

|

|

M. Nagaraj v. UOI

|

2006

|

Upheld constitutional amendments for consequential seniority but imposed conditions: State must show data on backwardness, inadequate representation, and efficiency.

|

Sets the current constitutional framework and conditions for providing reservation in promotion with consequential seniority. 8

|

|

K. Meghachandra Singh v. Ningam Siro

|

2019

|

Overruled N.R. Parmar. Held that seniority must be counted from the date of substantive appointment, not from the date a vacancy arose.

|

The current and most critical law on inter-se seniority between direct recruits and promotees. A major shift in jurisprudence. 7

|

|

B.K. Pavitra v. UOI-II

|

2019

|

Upheld Karnataka’s consequential seniority law, accepting the State’s data on representation and efficiency as satisfying the Nagaraj test.

|

A modern case study on how states can implement consequential seniority policies and the judiciary’s standard of review. 12

|

Section 6: The Legal Recourse — Challenging an Incorrect Seniority List

Knowing the law is the first step; knowing how to enforce your rights is the next. The process of challenging an incorrect seniority list is governed by specific procedures and strict timelines.

The Gradation List: Your Official Seniority Record

The official document that records an employee’s seniority is called a Gradation List or Seniority List.1 Its preparation is a formal process. Inspired by the principles of natural justice, the standard procedure involves 1:

1. Preparation of a Draft List: The department first prepares a provisional or draft seniority list.

2. Circulation for Objections: This draft list is circulated among all affected employees, who are given a specific time frame to submit their objections in writing.

3. Consideration of Objections: The department must duly consider all objections received.

4. Publication of Final List: After considering the objections, the final seniority list is published.

This process is not a mere formality. An employee’s right to submit objections is a crucial aspect of procedural fairness. A final seniority list published without first circulating a draft for objections is liable to be quashed.1

The Clock is Ticking: The Critical Importance of Timely Challenges

The law is strict about timeliness in service matters. The legal doctrine of delay and laches (unreasonable and unexplained delay) is applied rigorously to seniority disputes. Courts will refuse to entertain a challenge to a seniority list if the employee has slept on their rights and approached the court after a substantial and unexplained delay.1 A delay of several years is almost always fatal to a case.

The rationale for this strictness is public policy. The administration needs certainty. “Settled seniority” cannot be unsettled after a long time, as this would cause a domino effect of administrative chaos, affecting not just the petitioner but numerous other employees through reversions and changes in promotion, pay, and pension.1

However, the concept of delay is a double-edged sword. While an employee’s delay can be fatal to their claim, an inordinate delay by the government in preparing or finalizing a seniority list can be a ground for the court to intervene and protect the affected employee’s rights.1 This ensures that employees are not left in a state of perpetual uncertainty due to administrative inefficiency. The key message is twofold: be vigilant and act fast when your rights are affected, but also know that you are not entirely at the mercy of an inert administration.

The Aftermath: Legal Consequences of a Quashed Seniority List

If a court finds a seniority list to be illegal and quashes it, there are significant consequences. All consequential actions taken based on that list, such as promotions, are also liable to be cancelled.1 The court will typically direct the authorities to prepare a fresh, correct seniority list in accordance with the law and its judgment.

In the past, to avoid the hardship of reverting employees who were promoted based on a faulty list, courts sometimes directed the creation of supernumerary posts. However, the Supreme Court has now largely disapproved of this practice, citing the immense financial and administrative burden it places on the exchequer. Such directions are now rare and confined only to the unique facts of a particular case.1

Who to Sue? Identifying the Necessary Parties in a Seniority Dispute

A procedural complexity that often arises is the question of who must be impleaded as a respondent in a seniority case. There are conflicting judicial opinions on whether every single person who could potentially be affected by a redrawn seniority list needs to be made a party to the case.1 One view is that only the employer (the government department) is a “necessary party,” and individual employees are merely “proper parties.” Another view holds that since seniority is a civil right, all affected individuals are necessary parties. To avoid procedural hurdles and ensure a final and binding decision, the safest course of action is to implead all employees who are likely to be affected by the outcome of the litigation.

Conclusion: Protecting Your Career Progression with Expert Guidance

The law of seniority in Indian government services is a complex and dynamic field. As we have seen, it is a tapestry woven from constitutional principles, statutory rules, executive instructions, and a constantly evolving body of judicial precedents. The key takeaways for any government servant are clear:

● Seniority is a valuable, constitutionally protected civil right that is fundamental to your career progression.

● It is governed primarily by a strict hierarchy of rules, with the “length of continuous service” being the default and most fair principle.

● The legal landscape is not static. Landmark Supreme Court judgments have significantly altered long-standing principles, especially concerning the inter-se seniority of direct recruits and promotees, and the complex issue of consequential seniority for reserved categories.

● Protecting your rights is a time-sensitive matter. Delay in challenging an incorrect seniority list can be fatal to your claim.

Navigating this intricate maze requires not just knowledge but specialized legal expertise. An incorrect placement on a seniority list can have irreversible consequences, impacting decades of service and post-retirement life. It is imperative to seek timely and expert advice to understand your position and enforce your rights effectively.

Expert Legal Assistance for Your Service Matter: Patra’s Law Chambers

If your seniority has been incorrectly fixed, your promotion has been unfairly delayed, or your career progression is being hampered by any service matter, understanding your legal options is the first step toward a resolution. Patra’s Law Chambers is a premier law firm with specialized expertise and a proven track record in the niche area of service law.

Our team of dedicated advocates has extensive experience in successfully representing government servants in complex seniority disputes. We regularly appear before the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), State Administrative Tribunals (SAT), the High Courts, and the Supreme Court of India, ensuring that our clients’ rights are robustly defended at every level of the judicial system.

We understand the nuances of service jurisprudence and are committed to providing clear, strategic, and effective legal guidance. If you are facing a service-related issue, do not delay. Contact Patra’s Law Chambers for a consultation to understand and protect your valuable civil rights.

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

Resources:Navigating the Maze of Seniority A Complete Guide to Service Law in India.pdf

1. SENIORITY.docx

2. seniority for ad hoc service doctypes: supremecourt – Indian Kanoon, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=seniority%20for%20ad%20hoc%20service+doctypes:supremecourt

3. Ad-hoc service not to be counted for the purpose of seniority – ABMK Law Chambers, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://www.abmklaw.com/post/ad-hoc-service-not-to-be-counted-for-the-purpose-of-seniority

4. The Recognition of Pre-Regularization Service in Determining …, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/the-recognition-of-pre-regularization-service-in-determining-seniority/view

5. inter se seniority direct recruits and promotees – Indian Kanoon, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=inter%20se%20seniority%20direct%20recruits%20and%20promotees

6. Inter se seniority of direct recruits and promotees – instructions thereof – CGDA, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://cgda.nic.in/rti/SeniorityOrder24092015.pdf

7. Revised instruction relating to fixation of inter-se-seniority between …, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://dpar.mizoram.gov.in/uploads/qms/95110a8679a5a57ca725645c0fb87496/revised-instruction-relating-to-fixation-of-inter-se-seniority-between-direct-recruits-and-promotees-thereof-dt-28032023.pdf

8. Reservation in Promotion: Court in Review, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/reservation-in-promotion-court-in-review/

9. Reservation in Promotion – National Commission for Scheduled Castes, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://ncsc.aeologic.in/storage/special_events/qaGTFkfUq3crTg6omWEXrqjxNkYVBXrXAJPFl5Q1.pdf

10. Court cases related to reservation in India – Wikipedia, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_cases_related_to_reservation_in_India

11. Legal Analysis of Recent Judgments on Reservation Policies in India | SCC Blog, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/04/19/legal-analysis-of-recent-judgments-on-reservation-policies-in-india-legal-research-legal-news-updates/

12. Plain English Summary of the Judgment in B.K. Pavitra v Union of …, accessed on August 7, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/reports/consequential-seniority-plain-english-summary-of-the-judgment-in-b-k-pavitra-v-union-of-india-ii/