- Police inaction undermines fundamental rights, making writs a crucial legal remedy for accountability in India.

- The Indian Constitution empowers citizens to seek writs for police inaction, particularly through Calcutta High Court.

- Writs like Mandamus compel police to perform legal duties, addressing delays in FIR registration and investigations.

- Judicial intervention highlights the importance of timely and fair investigations, linking them to the right to life under Article 21.

- Many landmark judgments, such as Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh, reinforce strict police duties and accountability.

- Understanding preparatory conditions and gathering evidence is essential before filing a writ petition in the Calcutta High Court.

- Proactive use of writs in public interest cases demonstrates judicial willingness to ensure governance accountability and public welfare.

Police Inaction Writs in the Calcutta High Court 🏛️

AI Audio Overview:

Authored by the legal experts at Patra’s Law Chambers

1. Introduction: When Justice Stalls – Understanding Police Inaction in India

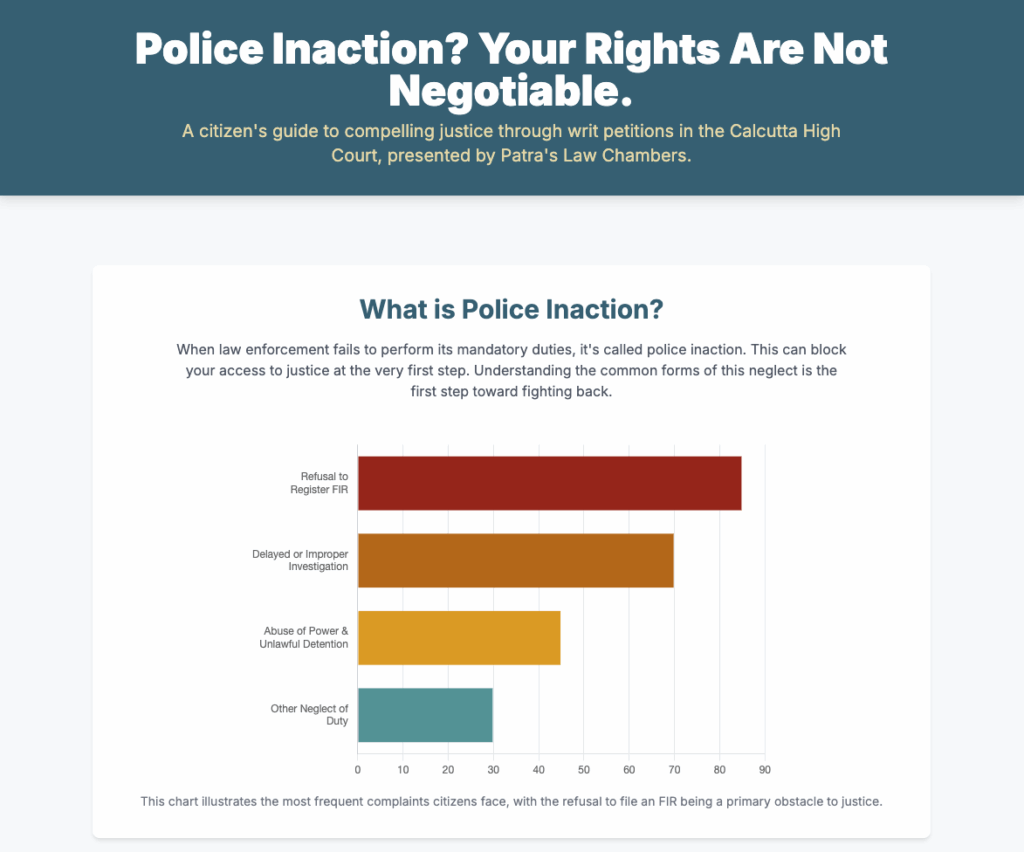

The foundational principle of a democratic society rests on the effective and impartial functioning of its law enforcement agencies. However, a pervasive challenge faced by citizens across India is police inaction, a distressing phenomenon ranging from the outright refusal to register a First Information Report (FIR) to conducting shoddy or delayed investigations, or even engaging in abuse of power. Such inaction directly impinges upon fundamental rights and undermines the very essence of the rule of law. When the primary guardians of law fail to act, citizens are often left vulnerable, their grievances unaddressed, and their pursuit of justice stalled.

In such critical circumstances, the Indian Constitution provides powerful remedies known as “writs.” These formal written orders, issued by the superior courts, serve as a beacon of hope, compelling public authorities, including the police, to perform their statutory and constitutional duties. Writs often represent a last resort when all other avenues for redressal prove futile.

This comprehensive guide aims to illuminate the legal landscape surrounding police inaction and the role of writs in compelling accountability. While the term “police inaction writ” is commonly used, it refers to seeking judicial intervention through specific types of constitutional writs. The focus here is particularly on the procedures and precedents within the Calcutta High Court, making this article highly relevant and locally pertinent for individuals and entities in West Bengal seeking legal recourse against police apathy.

The very necessity for citizens to approach High Courts with petitions alleging police inaction points to a significant systemic gap in the internal accountability mechanisms of the police force. If internal remedies, such as complaints to senior police officers or interventions by magistrates, were consistently effective and timely, the High Courts would not frequently encounter a large volume of such petitions.1 This prevalence of judicial intervention underscores that the High Courts serve as a crucial external check on the executive, particularly the police, stepping in to enforce duties and protect rights when internal systems fail to deliver justice. This dynamic highlights a continuous effort by the judiciary to ensure that law enforcement remains subservient to the rule of law and responsive to public grievances.

2. The Constitutional Backbone: Writs and Your Fundamental Rights

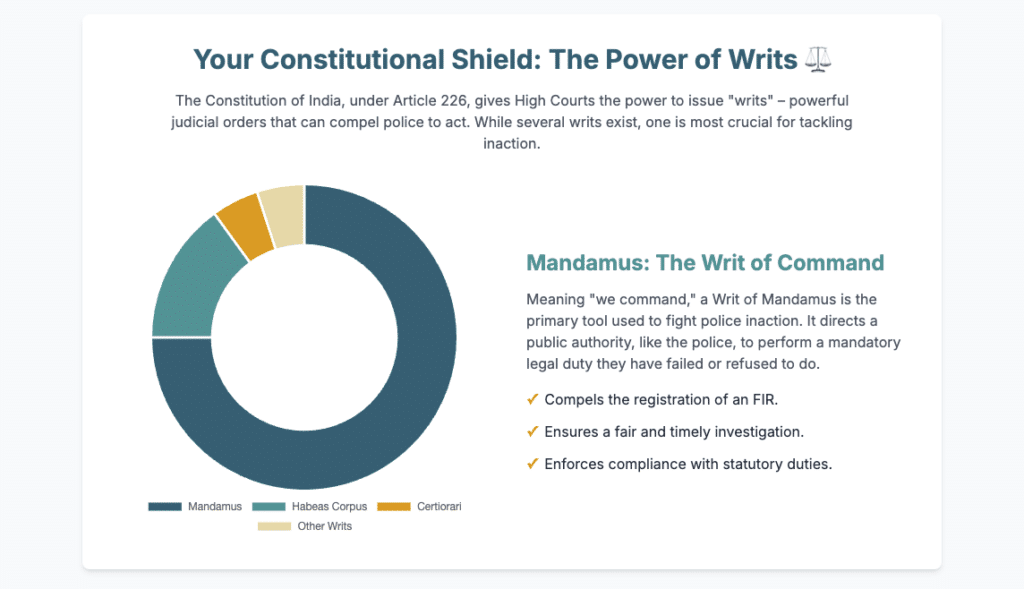

At the heart of India’s constitutional framework lies the power of judicial review, enabling superior courts to safeguard the rights of citizens. Writs are a manifestation of this power.

What are Writs?

Fundamentally, a writ is a formal written order issued by a court with the authority to do so.2 These orders command a person or entity to perform a specific act or to cease performing a specific action or deed.2 In India, this power is vested in the Supreme Court under Article 32 and in the High Courts under Article 226 of the Constitution.2 These articles provide citizens with the right to approach these courts directly when their Fundamental Rights have been violated.2

Supreme Court vs. High Court Writ Jurisdiction

While both the Supreme Court and High Courts can issue writs, there is a crucial distinction in their jurisdiction. Article 32 grants the Supreme Court the power to issue writs specifically for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights.2 In contrast, Article 226 empowers High Courts to issue writs not only for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights but also “for any other purpose”.3 This “any other purpose” clause significantly broadens the High Courts’ jurisdiction, allowing them to intervene in a wider array of cases where a legal right, even if not a fundamental one, has been infringed, or a public duty has been neglected. This expanded scope is particularly vital in cases of police inaction, where the grievance might stem from a violation of a statutory duty rather than a direct infringement of a Fundamental Right. Historically, before 1950, only the High Courts of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras possessed the power to issue writs; Article 226 extended this essential power to all High Courts across India.4

The inclusion of “for any other purpose” in Article 226 is not merely a linguistic addition; it represents a deliberate constitutional design to empower High Courts to address a wide spectrum of legal grievances, including police inaction, even if they do not directly violate fundamental rights.3 This broad power allows the judiciary to adapt to evolving societal needs and ensure justice where specific statutes might be silent or inadequate. It effectively positions the High Court as a court of last resort for administrative failures, including those of the police, ensuring that no public authority can escape accountability simply because their inaction does not fit neatly into a “fundamental rights violation” category. This flexibility reinforces the rule of law and helps prevent arbitrary governance by state actors.

Table 1: Key Writs for Addressing Police Inaction

Understanding the specific utility of each writ is crucial for identifying the appropriate legal remedy against police inaction. The table below clarifies how each writ can be employed in such scenarios, along with their key limitations.

| Writ Type | Meaning | Purpose/Usefulness against Police Inaction | Key Limitations | |

| Habeas Corpus | “To have the body of” | To challenge unlawful detention or imprisonment by police; ensures swift judicial review of alleged unlawful detention.2 Useful when police make illegal arrests, detain without legal justification, or fail to produce a person before a Magistrate within 24 hours.2 | Cannot be issued if detention is lawful, for disobedience to court, or if the court has no jurisdiction over detention.3 | |

| Mandamus | “We command” | To direct a public authority (including police officials) to perform a legal duty which they have failed or refused to perform.2 Most common writ against police inaction, compelling registration of FIRs, proper investigation, or compliance with statutory duties. | Duty must be mandatory, not discretionary.2 Cannot enforce non-statutory or purely private functions.2 Cannot be issued against the President or Governors.3 Generally, alternative remedies should be exhausted.2 | |

| Certiorari | “To be certified” or “To be informed” | To quash an order or decision of a lower court or tribunal (which can include quasi-judicial police authorities in certain contexts) that acted without or in excess of jurisdiction, or in violation of natural justice.2 Less common for direct police | inaction, but applicable if an illegal order stems from police procedural impropriety or lack of jurisdiction. | Issued after a case is heard and decided.2 Cannot be issued against legislative bodies or private individuals/bodies.2 |

| Prohibition | “To forbid” | To prevent a lower court or tribunal from exceeding its jurisdiction or acting against natural justice while a case is pending.2 Less directly applicable to police inaction, but relevant if a police authority is about to take an action outside its legal bounds due to inaction or improper process. | Issued during the pendency of proceedings.2 Can only be issued against judicial and quasi-judicial authorities.4 | |

| Quo-Warranto | “By what authority or warrant” | To prevent a person from holding a public office they are not entitled to.2 Not typically used for police | inaction itself, but for challenging the legitimacy of an officer holding a specific post if that illegitimacy leads to broader issues of non-performance or abuse of authority. | Can only be issued for a substantive public office of a permanent character created by statute or Constitution.4 Cannot be issued against private or ministerial offices.4 |

3. Unmasking Police Inaction: Cases Warranting Judicial Intervention

Police inaction manifests in various forms, each with distinct legal implications and remedies. Understanding these specific scenarios is crucial for determining the appropriate course of action.

Refusal to Register First Information Report (FIR)

One of the most common and critical forms of police inaction is the refusal to register an FIR. Under Section 154(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), it is a mandatory duty for the police to register an FIR if the information received discloses the commission of a cognizable offense.7 This duty is not discretionary; the Supreme Court in

Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh 13 unequivocally held that FIR registration is mandatory if a cognizable offense is disclosed.

Despite this clear legal mandate, police often refuse or delay FIR registration, citing reasons such as jurisdictional issues, the perception of a non-cognizable offense, or external pressure.1 Such refusal or delay has been termed a “serious dereliction of a statutory duty” and a violation of the Constitution by the Supreme Court.17

When faced with such a refusal, citizens have several remedies before resorting to a writ petition. Initially, the complainant can send the substance of the information in writing and by post to the concerned Superintendent of Police (SP) under Section 154(3) CrPC.7 If the SP is satisfied that a cognizable offense is disclosed, they are obligated to either investigate the case themselves or direct a subordinate officer to do so.7 Should this approach also fail, the aggrieved person can file a complaint directly before the Judicial Magistrate under Section 190 CrPC, who can take cognizance of the offense.7 Furthermore, the Magistrate has the power under Section 156(3) CrPC to direct the police to investigate the matter.9

The police’s mandatory duty to register FIRs highlights their critical “gatekeeping” role in the criminal justice system. When police refuse or delay FIR registration, they effectively shut down the legal process at its very inception, denying victims access to justice, regardless of the merits of their complaint. This exercise of power, when misused, can lead to widespread public distrust and a perception that the system serves the powerful rather than the vulnerable.17 The existence of statutory remedies (Sections 154(3) and 156(3) CrPC) and the ultimate availability of writ jurisdiction underscore the judiciary’s role in counteracting this gatekeeping abuse. These legal provisions are designed to bypass the initial failure, ensuring that the legal process can be initiated despite police inaction, thereby upholding the citizen’s right to report a crime and seek investigation.

Delayed or Improper Investigation

Beyond FIR registration, police inaction can manifest in the form of delayed, ineffective, or biased investigations. Section 173(1) CrPC mandates that every police investigation should be completed without unnecessary delay.12 Furthermore, the investigation must be fair, prompt, transparent, and judicious for both the victim and the accused.18

An investigation that is ineffective, unfair, unclear, irresponsible, or unduly delayed is not merely an administrative inefficiency; it is considered a violation of the fundamental right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution.18 Courts have expressed strong disapproval of such delays, terming them “unconscionable” and a breach of basic criminal jurisprudence.21

In instances of investigative lapses, the Supreme Court, in Sakiri Vasu v. State of U.P. and Ors., clarified that a Magistrate, despite the brief wording of Section 156(3) CrPC, possesses an implied power to direct the officer-in-charge of a police station to conduct a proper investigation and even to monitor the same.9 This empowers the lower judiciary to ensure the integrity of the investigative process. For more serious lapses, or when there is a loss of public confidence in the local police, the High Court can order the transfer of the investigation to an independent agency like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).18

The judiciary’s emphasis on prompt and fair investigation, and its direct link to Article 21, signifies that a proper investigation is viewed not just as a procedural step but as an integral component of substantive justice. Delays or shoddy investigations are not mere inefficiencies; they are constitutional violations. A delayed or improperly conducted investigation can lead to wrongful arrests, prolonged detention, denial of justice to victims, and ultimately, a breakdown of the rule of law. By linking investigative failures directly to Article 21, courts assert their constitutional mandate to ensure that the state machinery, including the police, acts diligently to protect citizens’ rights, thereby expanding the scope of judicial review over executive functions and compelling accountability for investigative inaction or malfeasance.

Unlawful Detention & Abuse of Power

Direct abuse of power by the police, particularly in the form of unlawful detention, torture, false implication, or brutality, constitutes a grave violation of fundamental rights and is a direct ground for judicial intervention. The writ of Habeas Corpus is specifically designed to challenge unlawful detention, compelling the authorities to produce the detained person before the court to examine the legality of their arrest.2 This includes situations where detention was not in accordance with established procedure (e.g., failure to produce before a Magistrate within 24 hours), arrest without violating any law, or arrest made under an unconstitutional law.2

Instances of police misconduct, such as physical abuse, torture, or false implication, are extensively documented, with numerous complaints being registered with bodies like the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).24 In such cases, courts have not only intervened to secure release but have also awarded compensation for violations of fundamental rights. Landmark judgments like

Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar 25,

Bhim Singh v. State of Jammu and Kashmir 25, and

Saheli v. Commissioner of Police, Delhi 25 established the principle of monetary relief for victims of illegal detention or police brutality, holding the State vicariously liable for the tortious acts of its employees. More recently, in

Somnath v. State of Maharashtra 27, compensation was directed to be paid by the individual police officer, signaling a potential shift towards greater personal accountability.

Other Forms of Neglect of Duty

Police inaction extends beyond criminal investigation to other spheres of public duty. Courts can intervene if police fail to maintain law and order, for instance, by not controlling mob violence, as highlighted in reports concerning the Musheedabad violence where local police were noted to be “completely inactive and absent”.28 Similarly, if police authorities disregard directives from lower courts or tribunals, a writ of mandamus can be sought to compel compliance.1 Instances where police fail to provide necessary protection despite requests, leading to harm, also fall under this category.30

While writs traditionally serve to correct past wrongs, such as quashing an illegal order or securing release from unlawful detention, there is an observable evolution towards a more preventive and supervisory role of the judiciary through the use of writs like Mandamus. This is evident in cases where courts compel police to perform duties that prevent disorder or ensure public welfare, moving beyond just individual rights enforcement to broader governance accountability. For example, in Upamanyu Bhattacharya v. State of West Bengal 31, a Public Interest Litigation sought a writ of mandamus against state and police authorities for delaying No Objection Certificates (NOCs) for a crucial metro project. This inaction, impacting public infrastructure and the fundamental rights of commuters, prompted the Calcutta High Court to hear the matter, demonstrating the judiciary’s willingness to intervene proactively to ensure administrative efficiency and public welfare. This signifies a shift where courts are not merely arbiters of disputes but active participants in ensuring that state machinery functions optimally for the benefit of society.

4. Preparable Conditions: Laying the Groundwork for a Writ Petition

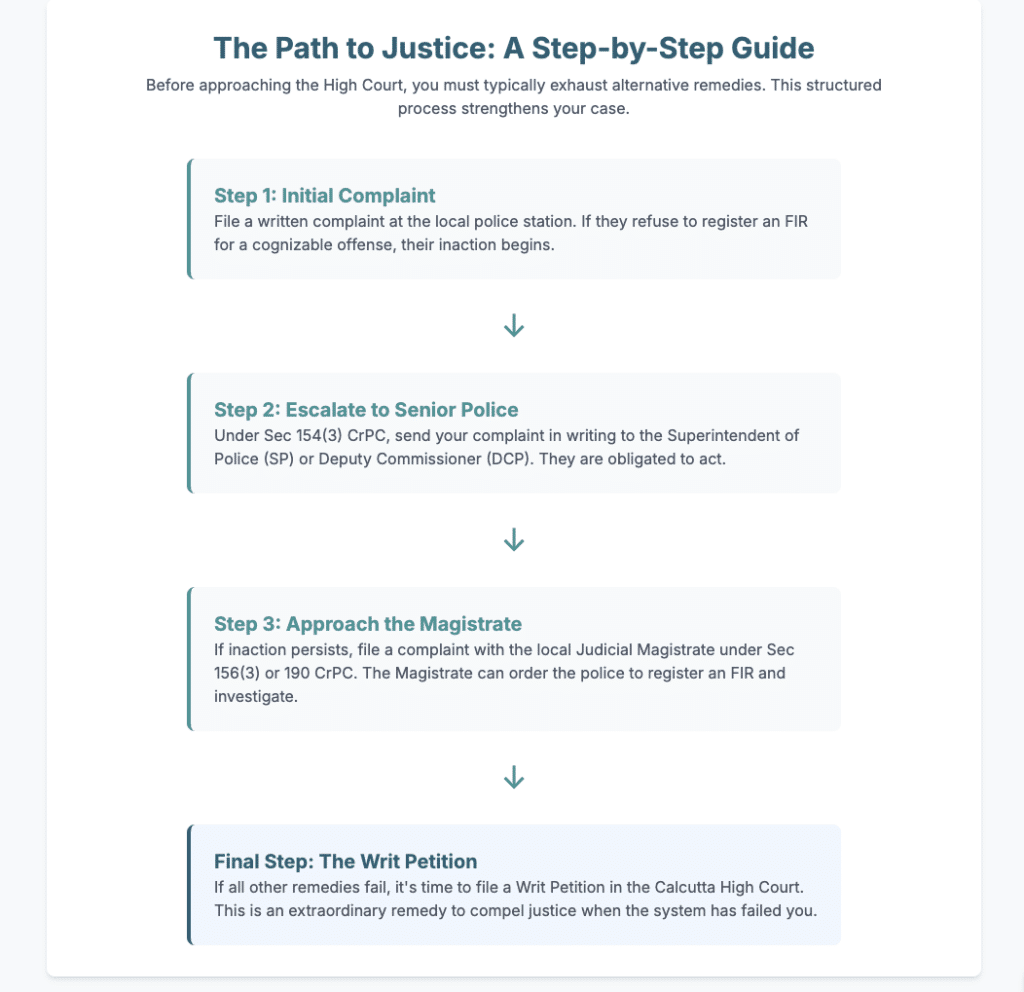

Before approaching the High Court with a writ petition against police inaction, certain preparatory conditions must generally be met to ensure the petition’s admissibility and strength.

Establishing a Clear Legal Right and Corresponding Public Duty

The petitioner must clearly demonstrate that a specific legal right belonging to them has been infringed, and that the police authority has a corresponding mandatory public duty which it has failed or refused to perform.2 It is crucial that the duty in question is a legal obligation, prescribed either by statute or case law, and not a discretionary function.2 A writ of mandamus, for instance, cannot be issued to compel performance of a duty that is purely discretionary or of a private nature.2

Demonstrating Demand for Performance and Refusal/Inaction

It is imperative for the petitioner to show that they formally demanded the performance of the duty from the concerned authority, and that this demand was met with refusal or inaction.2 This typically involves a systematic approach of sending written complaints to the Station House Officer (SHO) of the concerned police station, escalating the matter to higher police officials such as the Superintendent of Police (SP) or Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) under Section 154(3) CrPC, and potentially filing a complaint with the Judicial Magistrate under Section 190 or Section 156(3) CrPC.9 Maintaining records of all such communications, including acknowledgments and any responses, is vital.

Exhaustion of Alternative Remedies

Generally, a writ petition is considered an extraordinary remedy and a last resort. High Courts typically prefer that petitioners first exhaust all available alternative remedies under the law before invoking their writ jurisdiction.2 These alternative remedies include the statutory avenues provided under the CrPC, such as approaching the SP under Section 154(3) or the Magistrate under Section 156(3) or Section 190.7

However, there are exceptions to this rule. In “gross cases of grave injustice” or where fundamental rights are directly and severely violated, the High Court may entertain a writ petition without insisting on the exhaustion of alternative remedies.11 This discretion is exercised to ensure that justice is not delayed or denied due to procedural formalities in cases of clear constitutional breaches.

The requirement to exhaust alternative remedies before approaching the High Court for a writ acts as a significant procedural filter. While this is intended to prevent the High Courts from being overburdened with matters that can be resolved at lower levels, it also places a substantial initial burden on the aggrieved citizen to meticulously document every step of their interaction with the police and other authorities.9 This process, if not navigated carefully, can inadvertently lead to the dismissal of a legitimate writ petition on technical grounds. This highlights the critical role of legal professionals in guiding clients through this complex preliminary process, ensuring proper documentation and adherence to procedural prerequisites, thereby increasing the likelihood of a successful writ petition.

Importance of Documentary Evidence

Meticulous collection and preservation of all supporting evidence are paramount. This can include, but is not limited to, video or audio recordings of the incident, photographs (of injuries, property damage, or the scene), medical reports, written statements from independent witnesses with their contact details, and copies of all relevant documents such as detention slips, FIR copies (if any), and all correspondence with the police (complaints, acknowledgments, refusal letters).19 Such evidence is vital to substantiate the allegations of police inaction and to establish a clear “cause of action” before the court.

Bona Fide Intent

The writ petition must be filed in good faith, driven by a genuine desire for justice and not for malicious intent, personal vendetta, or to harass the police or other parties.13 Courts may dismiss petitions if the invocation of jurisdiction is found not to be bona fide.33

5. Filing a Police Inaction Writ in the Calcutta High Court: A Procedural Guide 🏛️

Filing a writ petition in the Calcutta High Court requires adherence to specific procedural rules and a clear understanding of its territorial jurisdiction.

Territorial Jurisdiction under Article 226(2)

A High Court’s power to issue writs is confined to its local territories.33 Under Article 226(2) of the Constitution, the Calcutta High Court can issue writs if the “cause of action,” wholly or in part, arises within its territorial jurisdiction, irrespective of where the government or authority against whom the writ is sought is physically located.33 This means that the police inaction itself, or the significant consequences of that inaction, must have occurred within West Bengal.

It is important to note that merely being aware of an issue in Calcutta, or submitting representations from Calcutta, does not automatically constitute a “cause of action” within the High Court’s jurisdiction. As illustrated in cases like ONGC v. NICCO 33, the facts pleaded must have a direct and integral nexus to the dispute. For instance, simply reading an advertisement or sending a bid from Calcutta was deemed insufficient to confer jurisdiction when the execution of the contract was elsewhere.33 Therefore, establishing a clear link between the police inaction and its occurrence or impact within West Bengal is crucial.

Specific Rules for Writ Petitions in Calcutta High Court

Applications under Article 226 in the Calcutta High Court are governed by specific rules, often grouped under its “Constitutional Writ Jurisdiction”.34 The High Court operates with distinct “Original Side” and “Appellate Side” jurisdictions for writ petitions, depending on the nature of the writ and the location of the respondents or records:

- Original Side: Applications for Writs in the nature of Mandamus, Prohibition, and Quo Warranto are generally dealt with by the Original Side if all the respondents reside, carry on business, or have their offices situate within the Ordinary Original Civil Jurisdiction of the High Court.34 Similarly, applications for a Writ of Certiorari are handled by the Original Side if the relevant records are located or available within its Ordinary Original Civil Jurisdiction.34

- Appellate Side: All other applications, including Habeas Corpus, are dealt with by the Appellate Side.34 Specifically, Habeas Corpus applications are made before the Division Bench handling the criminal business of the Appellate Jurisdiction.34

Step-by-Step Process

- Consultation with a Lawyer: Given the complexities of legal provisions, procedural rules, and the nuances of jurisdiction, consulting with an experienced lawyer specializing in constitutional and criminal law is essential.18 A lawyer can help identify the appropriate writ, determine the correct court side (Original or Appellate), and strategize the petition’s drafting.

- Drafting the Petition: A clear, concise, and factual written petition must be prepared. It should meticulously detail the specific incident of police inaction, the legal duty violated, the fundamental or legal right infringed, and the precise relief sought from the court.20 All supporting evidence collected should be annexed to the petition.

- Affidavits: The petition must be supported by an affidavit, a sworn statement affirming the truthfulness of the facts presented in the petition.

- Filing: The prepared petition, along with the required number of copies and court fees, must be submitted to the appropriate High Court registry (either the Original Side or Appellate Side, as determined by the nature of the writ and the cause of action).

- Service: Proper service of the petition on all respondents (e.g., the specific police officers, the Commissioner of Police, the State of West Bengal through its relevant departments) is mandatory. This ensures they receive a copy of the petition and are afforded an opportunity to be heard by the court.3

- Hearing: The court will schedule a hearing where arguments from both sides will be presented. Depending on the urgency of the matter and the prima facie case established, the court may grant interim orders, such as a stay of arrest, a direction for immediate investigation, or an order for the production of relevant records.

Key Considerations for a Strong Petition

- Clearly articulate the legal right that has been infringed and the specific public duty that the police have neglected.

- Provide a chronological and detailed account of all events, including every step taken to seek redressal from police authorities at lower levels, thereby demonstrating the exhaustion of alternative remedies.

- Attach comprehensive documentary evidence to support every factual assertion made in the petition.

- Ensure that the “cause of action” is meticulously established to fall squarely within the Calcutta High Court’s territorial jurisdiction, as interpreted by judicial precedents.33

The distinction between the “Original Side” and “Appellate Side” of the Calcutta High Court for different writ types, coupled with the nuanced interpretation of “cause of action” under Article 226(2) 33, adds a significant layer of strategic complexity to filing a police inaction writ. A lawyer’s ability to correctly identify the appropriate side and establish a strong jurisdictional link based on where the inaction occurred or its effects were felt (not merely where the petitioner resides) can significantly impact the petition’s admissibility and the speed of its resolution. This highlights that successful writ practice in the Calcutta High Court demands not only a profound understanding of constitutional law but also deep procedural mastery and the strategic ability to frame the “cause of action” to ensure the petition is entertained and heard efficiently.

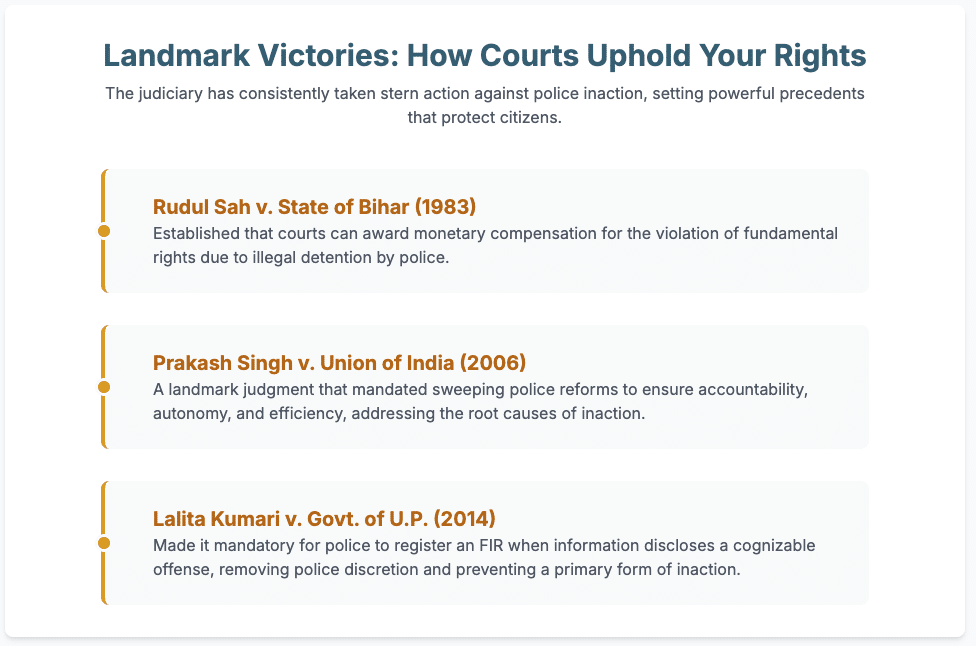

6. Landmark Judgments: Victories Against Police Inaction & Ensuring Accountability

Judicial pronouncements, particularly from the Supreme Court of India and various High Courts, serve as powerful precedents, guiding future cases and reinforcing the principles of police accountability and citizen rights. These judgments unequivocally demonstrate the courts’ willingness to take “stern action” against police inaction, thereby upholding the rule of law. The Indian legal landscape is rich with such precedents, illustrating the judiciary’s consistent commitment to intervening when law enforcement fails in its duties.

Table 2: Significant Judgments Upholding Writs Against Police Inaction

The following table presents a curated list of impactful judgments that exemplify the judiciary’s consistent stance against police inaction and the remedies provided. These cases illustrate the types of “stern action” taken by courts to ensure justice.

| Case Name | Year | Court | Key Principle/Issue | Outcome/Impact (Stern Action/Relief) |

| Lalita Kumari v. Government of Uttar Pradesh | 2014 | Supreme Court | Mandatory registration of FIR for cognizable offenses; preliminary inquiry only in limited cases. | Established a binding legal duty for police; officers refusing FIR can face disciplinary action.13 This judgment is foundational, ensuring that the first step of criminal justice is not arbitrarily blocked. |

| Sakiri Vasu v. State of U.P. and Ors. | 2008 | Supreme Court | Magistrate’s implied power under Section 156(3) CrPC to direct and monitor proper investigation. | Empowered lower judiciary to ensure effective investigation, reducing reliance on High Courts for initial lapses.9 This case provides a crucial avenue for citizens when police investigation is deficient. |

| Prakash Singh v. Union of India | 2006 | Supreme Court | Landmark judgment mandating police reforms, including establishment of State Security Commissions, fixed tenures for police chiefs, separation of investigation from law & order, and Police Complaints Authorities. | Directed systemic changes to enhance police autonomy, accountability, and efficiency.25 This goes beyond individual cases to address institutional issues within the police force. |

| Rudul Sah v. State of Bihar | 1983 | Supreme Court | Awarded compensation for illegal detention (14 years after acquittal), establishing the principle of monetary relief for fundamental rights violations under writ jurisdiction. | Paved the way for victims of police misconduct to receive compensation directly from the State, even without a civil suit.25 |

| Bhim Singh v. State of Jammu and Kashmir | 1985 | Supreme Court | Compensation awarded for illegal arrest and detention of an MLA, preventing him from attending assembly session. | Reaffirmed the importance of personal liberty and imposed pecuniary liability on the State for police excesses, emphasizing that such actions violate Article 21 and 22(2).25 |

| Saheli v. Commissioner of Police, Delhi | 1990 | Supreme Court | Compensation awarded to the mother of a 9-year-old child who died due to police beating (custodial violence). | Held the State vicariously liable for tortious acts of its employees, even if they exceeded their authority, highlighting misuse of sovereign power.25 |

| Sudhir M. Vora v. Commissioner of Police, Mumbai | 2004 | Bombay High Court | Writ of Mandamus sought against police for threatening, abusing, and coercing an individual into a monetary settlement. | Demonstrated the use of Mandamus to address police abuse of power and compel suitable action against errant officers.5 |

| Kalpana Pal vs State Of West Bengal & Ors | 2010 | Calcutta High Court | Allegations of police inaction where police were reluctant to interfere in their duty. | Calcutta High Court acknowledged being “flooded with petitions” alleging police inaction, indicating a widespread problem and the court’s readiness to intervene.1 |

| Shamit Sanyal vs State Of West Bengal & Ors | 2014 | Calcutta High Court | Writ petitions alleging “police inaction” where police did not consider it necessary to take action. | Held that writ petition alleging police inaction is maintainable before the Calcutta High Court, reinforcing its determination to address such matters.1 |

| Mrs. Charu Kishor Mehta vs State Of Maharashtra Ig | 2010 | Bombay High Court | Police inaction in not registering FIR despite detailed communication and request. | Court found police inaction unjust for not registering FIR and initiating investigation, emphasizing the duty to investigate.1 |

| Upamanyu Bhattacharya v. State of West Bengal | 2025 | Calcutta High Court | Public Interest Litigation seeking Mandamus against state/police inaction for delaying No Objection Certificates (NOCs) for Kolkata Metro Orange Line, violating Articles 14 & 21. | Calcutta High Court set to hear the PIL, demonstrating judicial intervention for public utility and constitutional obligations against administrative/police inaction.31 |

| Sukdeb Saha v. State of Andhra Pradesh | 2025 | Supreme Court | Writ petitions seeking transfer of investigation to CBI due to police inaction/lapses in suspicious student death case. | Supreme Court set aside High Court’s rejection, allowed CBI transfer, and laid down mental health guidelines, showing stern action against investigative failures and broader societal implications.22 |

| Vijayabai Vyankat Suryawanshi v. State of Maharashtra | 2025 | Bombay High Court | Police failed in their duty by not filing an FIR even after a complaint was submitted by the mother of a deceased Dalit law student in a custodial death case. | Court directed immediate FIR registration under BNS (new criminal code) and transfer of investigation to a Deputy Superintendent of Police-rank officer, emphasizing mandatory FIR duty in serious cases.35 |

| Justice Yashwant Varma Incident (Plea by Nedumpara) | 2025 | Supreme Court | Plea criticizing Centre/Delhi Police for non-registration of FIR despite in-house inquiry findings of “charred currency” at a High Court judge’s residence, alleging police inaction. | Highlights ongoing battle for FIR registration against police inaction even in high-profile cases, prompting calls for review of judicial immunity for judges.15 This demonstrates the pervasive nature of police inaction challenges. |

The Broader Impact of Judicial Intervention on Police Accountability

Judicial intervention through writ petitions has a multifaceted impact on police accountability:

- Deterrence: Court orders, especially those imposing compensation or directing disciplinary action against errant officers, act as a significant deterrent against future police misconduct and inaction. The prospect of judicial scrutiny compels greater adherence to legal duties.

- Systemic Reforms: Landmark judgments, such as Prakash Singh v. Union of India 25, have gone beyond individual case redressal to mandate systemic police reforms. These directives include the establishment of State Security Commissions, fixed tenures for police chiefs, separation of investigation from law and order functions, and the creation of Police Complaints Authorities, all aimed at fostering a more professional, independent, and accountable police force.

- Public Trust: Successful writ petitions against police inaction play a crucial role in restoring and reinforcing public faith in the justice system. When other avenues for redressal fail, the judiciary’s willingness to intervene sends a powerful message that justice can be obtained even against powerful state actors, thereby strengthening the democratic fabric.

The concept of “stern action” taken by courts against police inaction has evolved over time. Initially, it often implied disciplinary measures against individual officers. However, the development of jurisprudence, particularly with cases like Rudul Sah and Saheli 25, demonstrated a shift towards compensating victims from the State exchequer. While this provides immediate relief to victims, the fact that compensation often comes from public funds rather than directly from the errant police officer has raised questions about true individual accountability and its deterrent effect.26

However, recent developments, exemplified by cases like Somnath v. State of Maharashtra 27, where compensation was directed to be paid from the individual officer’s pocket, indicate a potential trend towards stricter individual liability. This development signifies a judicial push towards personalizing accountability. Nevertheless, this is often constrained by statutory protections for public servants, such as Section 197 CrPC 26, and limitation periods for initiating prosecution.27 This complex interplay suggests that “stern action” is a multifaceted concept, involving a combination of compensatory, disciplinary, and, in some instances, criminal consequences. The ongoing debates surrounding its effectiveness in truly reforming police behavior reflect the continuous struggle to balance victim redressal with the realities of state functioning and existing legal frameworks that can sometimes shield officers.

7. Conclusion: Empowering Citizens, Enforcing the Rule of Law ✨

Police inaction poses a significant threat to the rule of law and the fundamental rights of citizens in any democratic society. However, the Indian Constitution, through its powerful writ jurisdiction under Article 226, provides an indispensable and potent tool for individuals to hold law enforcement agencies accountable for their failures, negligence, or abuse of power. From compelling the registration of FIRs and ensuring fair investigations to challenging unlawful detentions and securing compensation for victims, the judiciary consistently demonstrates its resolve to intervene when the executive falters.

The consistent judicial pronouncements and the growing body of case law affirm that police duties are not discretionary but are legal obligations, the non-performance of which can lead to stern action from the courts. This vigilance, coupled with the availability of legal recourse, empowers citizens to assert their constitutional and legal entitlements, thereby strengthening the democratic fabric and fostering a more just and accountable system of governance.

For those who have been victims of police inaction, understanding these legal avenues is the first step towards securing justice. Do not hesitate to seek expert legal counsel to navigate these complexities and ensure your rights are protected.

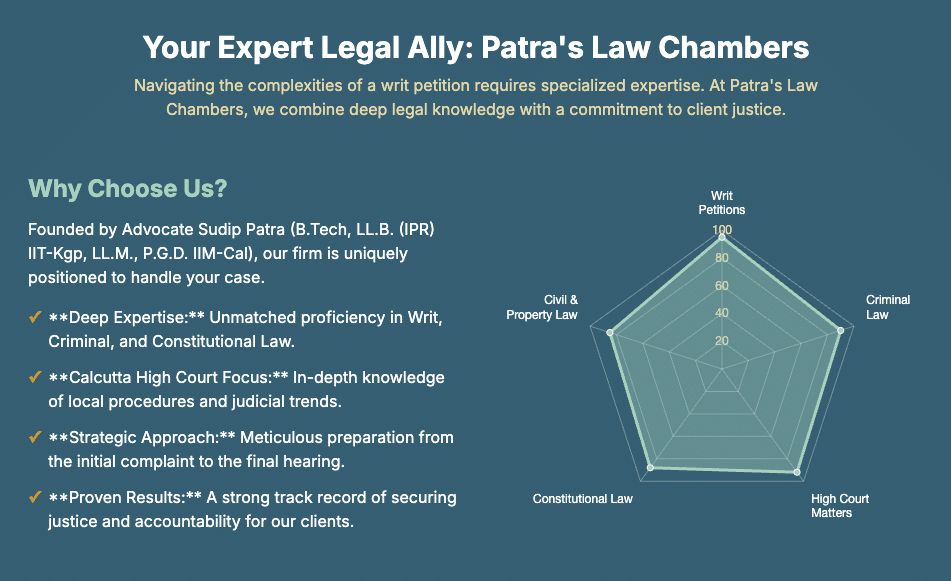

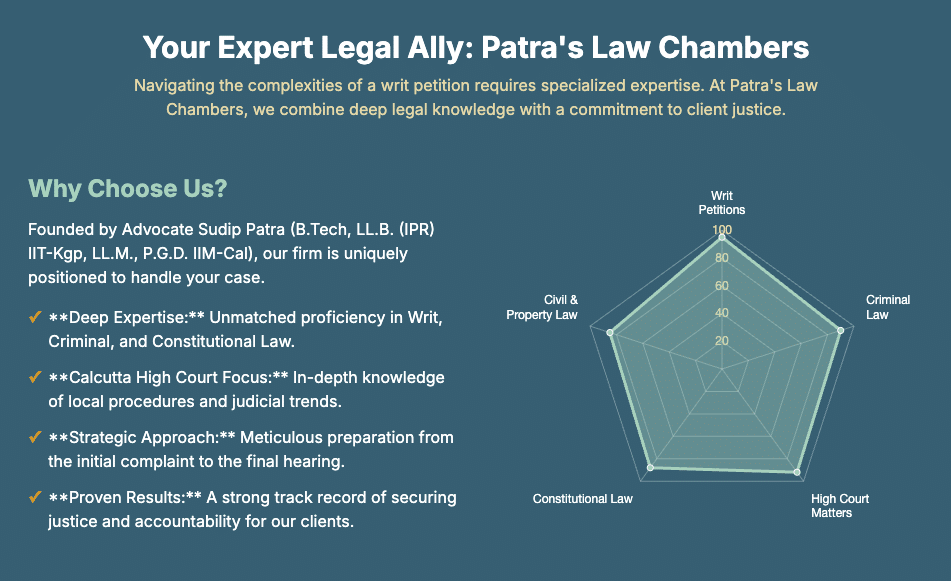

8. Patra’s Law Chambers – Your Trusted Legal Partner in Kolkata.

Contact Information:

- Website: patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Disclaimer: Please note: This article provides general legal information and does not constitute legal advice. For specific legal guidance regarding your unique situation, please contact our firm for a personalized and confidential consultation.

Resources: Your Legal Shield_ Navigating Police Inaction Writs in the Calcutta High Court 🏛️

Works cited:

- police inaction – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=police%20inaction%20%20%20%20%20

- Writs in the Indian Constitution – ClearTax, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://cleartax.in/s/writs

- Article 226 of the Indian Constitution – iPleaders, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/all-you-need-to-know-about-article-226-of-the-indian-constitution/

- Types of Writs In Indian Constitution – BYJU’S, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/types-of-writs-in-india/

- Writ of Mandamus On Commissioner of Police, Mumbai – Save Indian Family Foundation, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/568044405/Writ-of-Mandamus-on-Commissioner-of-Police-Mumbai-Save-Indian-Family-Foundation

- Writ of Mandamus – BYJU’S, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/writ-of-mandamus/

- What the Police Station does with a complaint pertaining to Non-cognizable offence? -..: BPR&D :.., accessed on July 29, 2025, https://bprd.nic.in/page/citizen_corner

- CHAPTER – XXXVIII (A) FIRST INFORMATION REPORT TO THE POLICE – Puducherry Police, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://police.py.gov.in/Police%20manual/Chapter%20PDF/CHAPTER%2038%20A%20First%20Information%20Report%20to%20the%20Police.pdf

- POWER OF MAGISTRATE TO DIRECT … – Patna High Court, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://patnahighcourt.gov.in/bja/PDF/UPLOADED/BJA/BLOGSJUDGMENT/1.PDF

- CrPC Section 154 – Information in cognizable cases – Devgan.in, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://devgan.in/crpc/section/154/

- Some important decision of Hon’ble Supreme Court of India on Criminal Law. – Maharashtra Police, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.mahapolice.gov.in/uploads/legal_matters/ImportantDecisionsOfHonerableSupremeCourtOnCriminalLaw.pdf

- CrPC : Information To The Police And Their Powers To Investigate …, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://devgan.in/crpc/chapter_12.php

- Articles – Landmark Judgments on FIR – The Law Advice, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.thelawadvice.com/articles/landmark-judgments-on-fir

- police inaction – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=police%20inaction%20%20%20%20&pagenum=3

- Plea in Supreme Court critcises Centre, Delhi Police for non-registration of FIR in Justice Varma incident – The Hindu, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/plea-in-supreme-court-critcises-centre-delhi-police-for-non-registration-of-fir-in-justice-varma-incident/article69834084.ece

- police inaction – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=police%20inaction

- Supreme Court slams widespread police delays in FIR registration – Voicepk.net, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://voicepk.net/2025/07/supreme-court-slams-widespread-police-delays-in-fir-registration/

- What can you do against Police Inaction? – Nyaaya, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://nyaaya.org/nyaaya-weekly/what-can-you-do-against-police-inaction/

- Exploring Legal Remedies for police inaction in India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://xpertslegal.com/blog/exploring-legal-remedies-for-police-inaction-in-india/

- How to File a Complaint Against Police Misconduct in India – Rest The Case, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/where-to-file-a-complaint-against-the-police

- Court shocked by ‘deliberate delay’ in probing FIR | Mumbai News – Times of India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/court-shocked-by-deliberate-delay-in-probing-fir/articleshow/122927529.cms

- Mental Health Integral Component of Right to Life – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/sukdeb-saha-v-state-of-andhra-pradesh-mental-health-integral-component-of-right-to-life/

- J U D G M E N T – Supreme Court of India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2020/27483/27483_2020_17_1501_57642_Judgement_04-Dec-2024.pdf

- PoliceCases | National Human Rights Commission India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://nhrc.nic.in/policecases

- Legal Accountability of the Police in India – Centre for Law & Policy Research, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://clpr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Police-Accountability-CLPR.pdf

- LEGAL ACCOUNTABILITY OF POLICE IN INDIA: AN ANALYSIS – IJNRD, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2209214.pdf

- Compensation Without Criminal Prosecution in Police Misconduct: Insights from SOMNATH v. Maharashtra – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/compensation-without-criminal-prosecution-in-police-misconduct:-insights-from-somnath-v.-maharashtra/view

- HC Panel Report: Police Inactive During Musheedabad Violence, Local Leaders Implicated | India Today, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDOiOm4DwZY

- police inaction doctypes: kolkata – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=police%20inaction+doctypes:kolkata

- HIGH COURT JULY 2025 WEEKLY ROUNDUP | 2006 Mumbai Train Blasts Acquittals; IELTS Scam; PRADA Kolhapuri Chappal Case; and more – SCC Online, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/07/27/high-court-weekly-roundup-july-2025-on-mumbai-train-blast-ielts-scam-prada/

- Public Money Lost, Metro Work Halted: Calcutta HC to Hear PIL on Orange Line Delay, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://lawbeat.in/top-stories/public-money-lost-metro-work-halted-calcutta-hc-to-hear-pil-on-orange-line-delay-1514068

- Powers of the High Court – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/powers-of-the-high-court/

- Article 226 – Where Must the “Action” be Instituted? – SCC Online, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/02/22/article-226-where-must-the-action-be-instituted/

- Rules of High Court at Calcutta relating to Applications under Article …, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/23892089/

- Bombay HC orders FIR in Dalit law student’s custodial death after arrest in 2024 protest over atrocities on Hindus in Bangladesh – SCC Online, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/07/10/bombay-hc-orders-fir-dalit-law-student-custodial-death/

- ‘He’s still judge’: CJI slams lawyer over indecorous reference to Justice Varma, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/hes-still-judge-cji-slams-lawyer-over-indecorous-reference-to-justice-varma-101753077212607.html