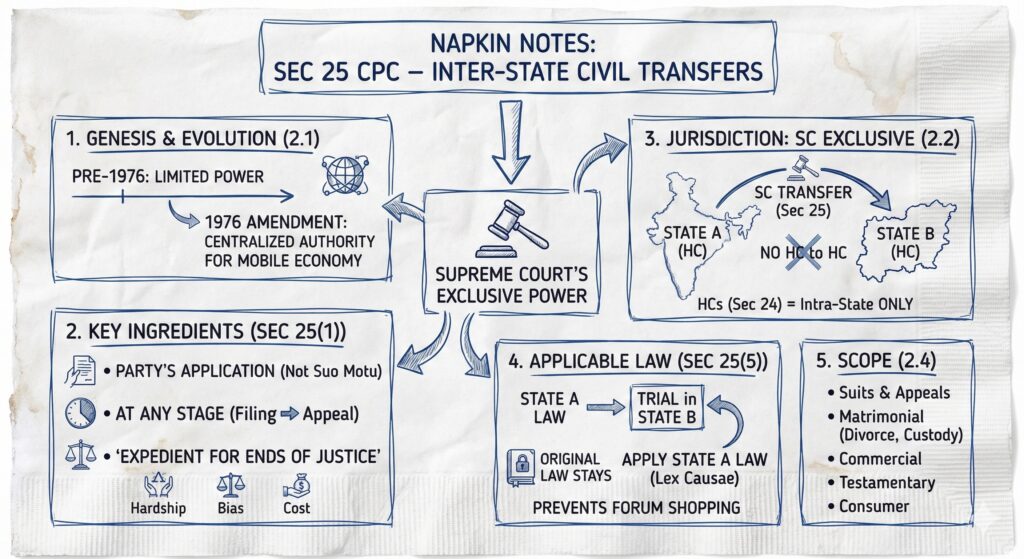

- Supreme Court holds exclusive power under Section 25 CPC to transfer suits between different states for the ends of justice.

- Law of the Transferor Court: transferee court applies the substantive law of the original forum per Section 25(5) CPC.

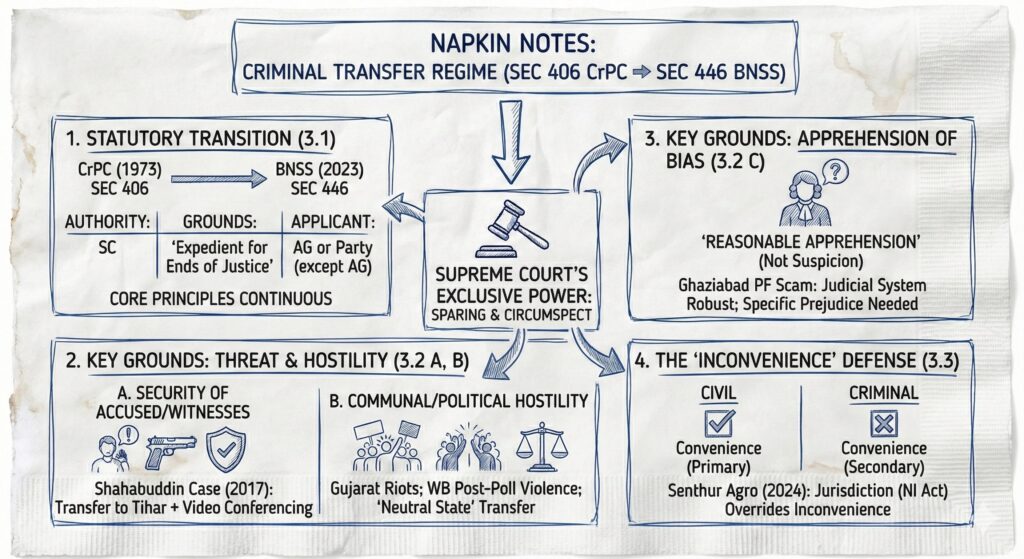

- Criminal transfers (formerly Section 406 CrPC, now Section 446 BNSS) are rare and require proof of threat to fair trial or witness safety.

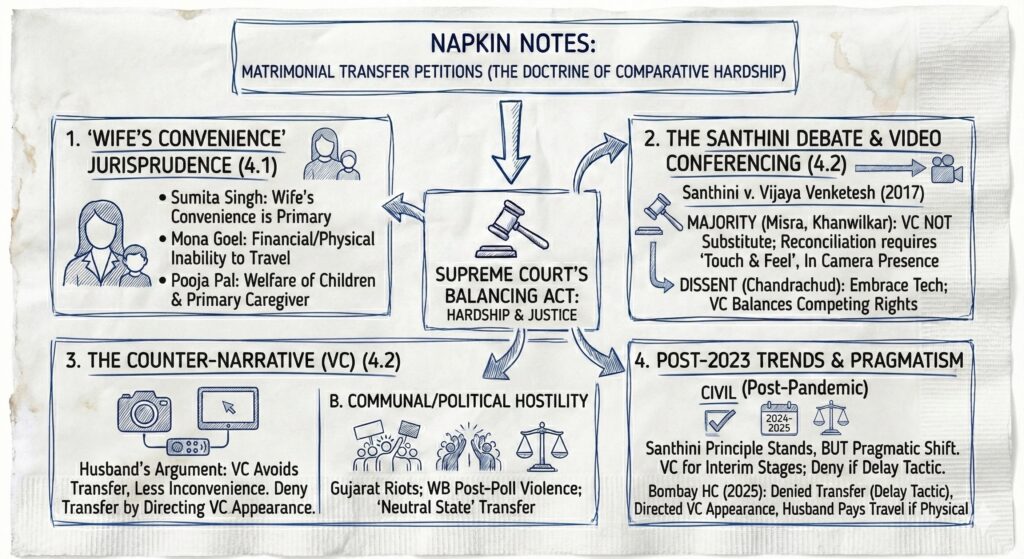

- Matrimonial transfers favor the wife’s convenience and child welfare, balanced against video conferencing and delay-tactics concerns.

- Supreme Court may use Article 142 to grant divorce or final relief within a transfer petition to achieve complete justice.

- Article 139A enables withdrawal or constitutional transfers to ensure uniformity in substantial questions of law across High Courts.

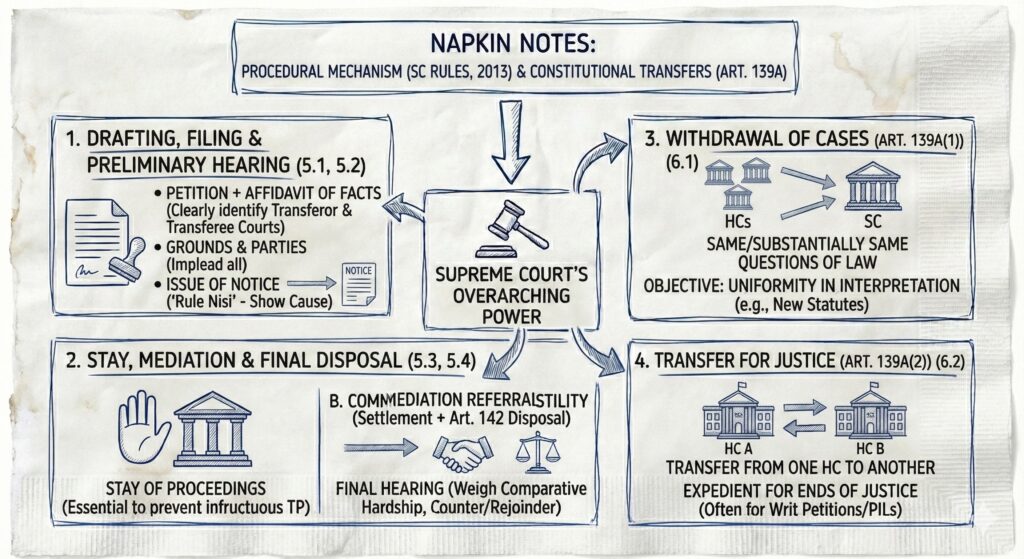

- Procedure governed by Supreme Court Rules, 2013: affidavit support, Rule Nisi, service, stays, mediation, and final hearing requirements.

LAW OF TRANSFER PETITIONS IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

1. Introduction: The Geopolitics of Justice in a Federal Framework

The administration of justice in the Republic of India is organized across a vast and diverse federal topography. With a hierarchy of courts spanning over 3.2 million square kilometers, 28 states, and 8 union territories, the physical location of a legal dispute often determines the accessibility, efficacy, and fairness of the judicial outcome. In a unified judiciary where the Supreme Court of India sits at the apex, the “venue” of a trial is not merely a matter of geographical convenience but a substantive component of the fundamental right to a fair trial under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

The concept of “Transfer of Cases”—the judicial shifting of a lawsuit, appeal, or criminal proceeding from one state jurisdiction to another—is the mechanism by which the Indian legal system corrects the imbalances imposed by geography, local prejudice, or comparative hardship. This power, vested exclusively in the Supreme Court for inter-state transfers, represents an extraordinary remedy. It is a power that disrupts the natural flow of territorial jurisdiction, which ordinarily dictates that a case must be tried where the cause of action arose or where the crime was committed. To disturb this natural presumption requires a compelling case for the “ends of justice.”

This report provides an exhaustive, expert-level analysis of the legal, procedural, and jurisprudential landscape of Transfer Petitions in the Supreme Court of India. It examines the statutory bedrock of Section 25 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), 1908, the evolving criminal jurisprudence under Section 406 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973 (and its successor, Section 446 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023), and the constitutional mandate under Article 139A.

Furthermore, this treatise delves into the sociological dimensions of these transfers, particularly in matrimonial disputes where the “doctrine of comparative hardship” has evolved into a distinct branch of gender jurisprudence. It scrutinizes the procedural rigors mandated by the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, the issuance of notices (Rule Nisi), and the imposition of stays. Finally, it outlines the practical ambit of the Supreme Court’s power, concluding with a profile of Patra’s Law Chambers, a specialized legal firm facilitating access to these high-level judicial remedies.

If you want to get a consultation regarding any Supreme Court matter, you can click here.

2. The Civil Transfer Regime: Section 25 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908

2.1 The Statutory Genesis and Evolution

The power to transfer civil suits is governed principally by Section 25 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), 1908. However, the current breadth of this section is a result of the Amendment Act of 1976. Prior to 1976, the power of the State Government to transfer cases was limited, and the Supreme Court’s direct intervention in civil transfers was not as explicitly codified as it is today. The 1976 amendment was a legislative recognition that in a mobile, integrated economy, civil disputes would increasingly span across state borders, necessitating a central judicial authority to adjudicate the appropriate forum.1

Textual Analysis of Section 25

Section 25(1) of the CPC states:

“On the application of a party, and after notice to the parties, and after hearing such of them as desire to be heard, the Supreme Court may, at any stage, if satisfied that an order under this section is expedient for the ends of justice, direct that any suit, appeal or other proceeding be transferred from a High Court or other Civil Court in one State to a High Court or other Civil Court in any other State.” 1

This provision contains several critical legal ingredients:

- “On the application of a party”: Unlike certain high court powers which can be exercised suo motu, Section 25 primarily contemplates a motion moved by a litigant.

- “At any stage”: The transfer can be sought at the stage of filing, during evidence, or even at the appellate stage, providing flexibility to the ends of justice.

- “Expedient for the ends of justice”: This is the controlling phrase. It grants the Supreme Court wide discretionary amplitude. It does not define “justice” rigidly, allowing the Court to mold relief according to the unique facts of each case, whether it be financial destitution, physical disability, or the threat of local bias.

2.2 Jurisdiction: The Exclusive Domain of the Supreme Court

A common misconception arises regarding the concurrent powers of High Courts under Section 24 and the Supreme Court under Section 25. The Supreme Court has clarified in no uncertain terms that the power to transfer a case from one state to another is exclusively vested in the Supreme Court.

In Durgesh Sharma v. Jayshree Sharma (2008) and reiterated in subsequent rulings involving the Gauhati High Court (which serves multiple states), the Supreme Court settled the position: A High Court can transfer cases within its own territorial jurisdiction or administrative control. It cannot transfer a case to a court subordinate to a different High Court. Even if two states share a High Court (e.g., Punjab and Haryana), the transfer mechanisms are nuanced, but for distinct High Courts (e.g., Delhi to Bombay), Section 25 is the sole remedy.3

2.3 The “Law of the Transferor Court” Principle

One of the most intellectually stimulating aspects of Section 25 is the resolution of conflict of laws. When a case is transferred from State A to State B, which state’s procedural or local amendments apply?

Section 25(5) of the CPC provides the statutory answer:

“The law applicable to any suit, appeal or other proceeding transferred under this section shall be the law which the Court in which the suit, appeal or other proceeding was originally instituted ought to have applied to such suit, appeal or proceeding.” 2

This provision creates a “legal fiction.” Even though the trial takes place physically in the Transferee Court (e.g., in Delhi), the Judge must apply the substantive law that would have been applied by the Transferor Court (e.g., in Chennai). This prevents “forum shopping” where a party might seek transfer solely to take advantage of a more favorable legal interpretation or local amendment in another state. The transfer changes the venue, not the lex causae (law of the cause).

2.4 The Scope of “Civil Proceedings”

The ambit of Section 25 extends beyond simple civil suits. It encompasses:

- Matrimonial Proceedings: Divorce, Restitution of Conjugal Rights (RCR), Child Custody (Guardians and Wards Act).

- Testamentary Suits: Probate and Letters of Administration.

- Commercial Disputes: Contractual breaches, intellectual property infringement suits filed in disparate jurisdictions.

- Consumer Complaints: Transfers of appeals pending before State Consumer Commissions (though often governed by specific consumer protection statutes, the plenary power remains).

3. The Criminal Transfer Regime: From Section 406 CrPC to Section 446 BNSS

While civil transfers often revolve around convenience, criminal transfers strike at the heart of the “integrity of the trial.” The presumption in criminal law is territoriality—a crime must be investigated and tried where it occurred (lex loci delicti). Displacing this presumption requires evidence that the local atmosphere is so vitiated that a fair trial is impossible.

3.1 The Statutory Transition: CrPC vs. BNSS

For decades, Section 406 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 governed this field. With the enactment of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023, the provision has been re-numbered as Section 446, though the core legal principles remain largely continuous.4

Comparative Analysis of Provisions

| Feature | Section 406 CrPC (1973) | Section 446 BNSS (2023) |

| Authority | Supreme Court of India | Supreme Court of India |

| Grounds | “Expedient for the ends of justice” | “Expedient for the ends of justice” |

| Applicant | Attorney General or “Party Interested” | Attorney General or “Party Interested” |

| Procedural Requirement | Application supported by Affidavit (except by AG) | Application supported by Affidavit (except by AG) |

| Scope | Transfer between High Courts or Criminal Courts under different High Courts | Transfer between High Courts or Criminal Courts under different High Courts |

While the text is similar, the context of its application is evolving. The BNSS emphasizes the use of technology and expedited justice, which may influence how “ends of justice” is interpreted in the future—potentially favoring digital transfers (video conferencing) over physical ones.

3.2 Key Grounds for Criminal Transfer

The Supreme Court exercises this power “sparingly and with great circumspection”.7 The burden of proof lies heavily on the petitioner to demonstrate that the transfer is necessary.

A. Threat to the Security of the Accused or Witnesses

The most compelling ground for transfer is the physical safety of the parties. If an accused person cannot attend court without risking assassination, or if witnesses are being systematically intimidated by a powerful accused, the “fairness” of the trial is compromised.

- The Shahabuddin Case (2017): This case is a watershed in transfer jurisprudence. Mohammad Shahabuddin, a politician with a significant criminal history, was incarcerated in Bihar. The Supreme Court, recognizing that his presence in Bihar jails allowed him to influence witnesses and intimidate the victim’s family, ordered his transfer to Tihar Jail in Delhi.9 The Court noted that the “Majesty of Justice” cannot countenance a situation where witnesses testify under the shadow of fear. Crucially, the trial was directed to be conducted via video conferencing, bridging the distance between the accused (in Delhi) and the court (in Bihar).9

B. Communal or Political Hostility

When the social atmosphere in a region is so surcharged with communal or political passion that a detached and impartial verdict is unlikely, the Court transfers the case to a “neutral” state.

- Gujarat Riots Cases: Several cases related to the 2002 Gujarat riots were transferred to Maharashtra to ensure that the polarizing local environment did not affect the judicial officers or witnesses.

- West Bengal Post-Poll Violence (2021-2023): In Md. Anisur Rahaman v. State of West Bengal and related matters, petitioners sought transfer of murder trials out of West Bengal, alleging state complicity. The Supreme Court, while cautious about casting aspersions on the state judiciary, has emphasized that if the state machinery acts “hand in glove” with the accused, or if the “fair trial” is in peril, transfer is the only remedy.8

C. Apprehension of Bias in the Judiciary

This is a delicate ground. Allegations that a specific judge or the entire state judiciary is biased are viewed with skepticism. In Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College of Law v. Union of India (1993), the Court held that a transfer is justified only if there is a “reasonable apprehension” of bias, not merely a subjective suspicion.13 In CBI v. Judicial Officers (Ghaziabad PF Scam), the Court refused to transfer a case merely because the accused were judicial officers, holding that the judicial system is robust enough to try its own unless specific prejudice is shown.7

3.3 The Defense of “Inconvenience” in Criminal Cases

A critical distinction exists between civil and criminal transfers regarding “convenience.” In civil cases, convenience is a primary factor. In criminal cases, it is secondary.

- Shri Senthur Agro and Oil Industries v. Kotak Mahindra Bank (2024): The petitioner sought to transfer a Section 138 Negotiable Instruments Act case (cheque bounce) from Chandigarh to Tamil Nadu, citing inconvenience. The Supreme Court dismissed the petition, ruling that the jurisdictional fact (where the cheque was presented) determines the venue. The inconvenience of the accused in traveling to Chandigarh is not a sufficient ground to override the statutory jurisdiction conferred by the legislature.14

4. Matrimonial Disputes: The Doctrine of Comparative Hardship

The vast majority of Transfer Petitions filed in the Supreme Court arise from matrimonial discord. Typically, these involve a husband filing for divorce or restitution in his home state, and the wife seeking transfer to her parental home or current residence.

4.1 The “Wife’s Convenience” Jurisprudence

For decades, the Supreme Court has adopted a protective approach towards women in transfer petitions, acknowledging the socio-economic disparities in Indian society.

- Sumita Singh v. Kumar Sanjay: The Court laid down the dictum that in matrimonial proceedings, “it is the wife’s convenience that must be looked at.”.15

- Mona Aresh Goel v. Aresh Satya Goel (2000): The Court reiterated that the financial and physical inability of the wife to travel to a distant court is a valid ground for transfer.1

- Pooja Pal v. Union of India (2016): The Court expanded this to include the “welfare of children.” If a mother is the primary caregiver of a minor child, compelling her to travel for litigation would indirectly punish the child. Thus, the transfer is allowed not just for the wife’s benefit, but for the child’s best interest.1

4.2 The Counter-Narrative and Video Conferencing (The Santhini Debate)

This “wife-centric” approach faced a significant challenge with the advent of video conferencing (VC). Husbands began arguing that instead of transferring the case (which inconveniences the husband), the wife could appear via VC.

Santhini v. Vijaya Venketesh (2017)

This judgment by a 3-judge bench is the locus classicus on the intersection of technology and matrimonial transfers.

- The Issue: Can a request for transfer be denied by directing the wife to appear via Video Conferencing?

- The Majority (CJI Dipak Misra & J. Khanwilkar): Held that VC is not a complete substitute for physical presence in matrimonial matters. They reasoned that matrimonial disputes involve sensitive reconciliation proceedings, often conducted in camera, which require the “touch and feel” of the physical courtroom. The emotional nuances and the statutory mandate for reconciliation under the Family Courts Act could be lost in a digital interface. Therefore, a transfer cannot be denied solely on the ground that VC is available.16

- The Dissent (J. D.Y. Chandrachud): Argued that the judiciary must embrace technology. He posited that insisting on physical travel in a country as vast as India places an undue burden on litigants and that VC balances the competing rights of both spouses effectively.

Post-2023 Trends

Despite the Santhini majority, the post-pandemic judicial landscape has seen a pragmatic shift. In 2024 and 2025, while the Santhini principle stands, Courts are increasingly using VC for interim stages or when the transfer petition is perceived as a delay tactic.

- Bombay High Court (2025): In a recent ruling, the High Court denied a transfer, noting it was a strategic attempt to delay, and instead directed the Family Court to allow the wife to appear via VC, with the husband bearing the costs of her physical travel if strictly necessary for evidence.19

4.3 Divorce under Article 142 in Transfer Petitions

A seismic shift in practice has occurred with the Supreme Court’s willingness to invoke Article 142 (Power to do complete justice) within a Transfer Petition.

- Shilpa Sailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan (2023): A Constitution Bench held that the Supreme Court can grant a decree of divorce on the ground of “irretrievable breakdown of marriage” directly, without remitting the parties to the Family Court.

- Implication: When hearing a TP, if the Court sees the marriage is dead, it can bypass the transfer entirely and simply end the marriage. This saves years of litigation. In Rinku Baheti v. Sandesh Sharda (2024), the Court utilized this power to dissolve a childless marriage despite one party’s opposition, prioritizing the “ends of justice” over procedural formalities.20

5. Procedural Mechanism: The Supreme Court Rules, 2013

#image_title

The filing and adjudication of Transfer Petitions are strictly governed by Order XLI of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013. A mastery of these rules is essential for the practitioner.

5.1 Drafting and Filing Requirements

- Format: The petition must be in writing, supported by an Affidavit of Facts. It must clearly identify the Transferor Court (where the case is) and the Transferee Court (where it is sought to be moved).23

- Grounds: The petition must concisely set out the grounds (e.g., financial hardship, threat to life, lack of jurisdiction).

- Parties: All parties to the original suit must be impleaded.

5.2 The Preliminary Hearing and “Rule Nisi”

Upon filing, the Registry lists the matter for a “Preliminary Hearing” before a Single Judge or a Division Bench.

- Issue of Notice: If the Court finds prima facie merit, it issues “Notice” to the Respondent. In older legal parlance and in constitutional matters, this is akin to a “Rule Nisi” (a rule to show cause). The Court effectively says, “We intend to transfer this case; show cause why we should not.”.24

- Service of Notice: The notice must be served on the respondent, often through the lower court or via speed post/email (“Dasti service”).

5.3 Stay of Proceedings

Crucially, the petitioner invariably seeks an Ex-Parte Stay of the proceedings in the Transferor Court.

- Why? If the lower court continues the trial or passes a final order while the TP is pending in the Supreme Court, the TP becomes infructuous.

- The Order: The Supreme Court often orders: “Issue Notice. In the meantime, further proceedings in Case No. X pending before the Family Court at Y shall remain stayed.”.26 This halts the lower court entirely until the Supreme Court decides the transfer.

5.4 Mediation and Final Disposal

- Mediation Referral: In matrimonial TPs, the Supreme Court frequently directs parties to the Supreme Court Mediation Centre. If the parties settle (e.g., agree to a Mutual Consent Divorce), the Court records the settlement and disposes of all pending cases (criminal and civil) in one order, often using Article 142.26

- Final Hearing: If mediation fails, the matter is heard on merits. The Respondent files a “Counter Affidavit,” and the Petitioner files a “Rejoinder.” The Court then weighs the comparative hardship and passes a final order: either allowing the transfer or dismissing it.

6. Constitutional Transfers: Article 139A

Distinct from the statutory powers under the CPC and CrPC is the constitutional power under Article 139A.

6.1 Withdrawal of Cases (Art. 139A(1))

When cases involving the “same or substantially the same questions of law” are pending before the Supreme Court and one or more High Courts, or two different High Courts, the Supreme Court can “withdraw” these cases to itself.

- Objective: To ensure uniformity in the interpretation of constitutional or central laws. Instead of different High Courts giving conflicting rulings on a new statute (e.g., the validity of the Aadhaar Act or GST laws), the Supreme Court withdraws all such petitions and decides the question of law authoritatively.27

6.2 Transfer for Justice (Art. 139A(2))

This clause empowers the Court to transfer any case, appeal, or proceeding from one High Court to another if “expedient for the ends of justice.” This is the constitutional equivalent of Section 25 CPC but is often used for Writ Petitions and public interest litigations that do not fall strictly under “civil suits”.29

7. Commercial Transfers and Forum Shopping

In the commercial sphere, Transfer Petitions are a strategic tool against “Forum Shopping.”

7.1 Cross-Suits and Consolidation

Commercial entities often race to file suits in their preferred jurisdictions (e.g., a vendor filing in Delhi vs. a buyer filing in Mumbai). This leads to a “multiplicity of proceedings” over the same contract.

- Judicial Approach: To prevent conflicting judgments, the Supreme Court typically transfers the subsequent suit to the court where the first suit was filed, or consolidates both suits in a court that has the most significant connection to the cause of action.31

7.2 The “Balance of Convenience” in Business

Unlike matrimonial cases where the “weaker” party (wife) is favored, commercial transfers are decided on “hard” metrics:

- Location of the property/goods.

- Location of the majority of witnesses and documents.

- Applicability of exclusive jurisdiction clauses in the contract (though Section 25 can override contractual clauses if justice demands it).

8. Conclusion

The power of Transfer Petition is a high-prerogative remedy that serves as the “safety valve” of the Indian judicial federation. Whether it is shielding a vulnerable spouse from harassment, protecting a witness from a warlord, or preventing a constitutional crisis through conflicting High Court judgments, the transfer jurisdiction underscores the Supreme Court’s role not just as a court of appeal, but as a court of equity and complete justice.

The evolution from strict territoriality to the “doctrine of comparative hardship,” and now to the “virtual courts” era, demonstrates that while the venue may change, the pursuit of a fair trial remains the constant pole star of this jurisprudence.

9. Legal Assistance: Patra’s Law Chambers

The complexity of filing Transfer Petitions—involving intricate affidavits, stay applications, and the invocation of constitutional powers like Article 142—requires specialized legal expertise. Patra’s Law Chambers is a premier law firm dedicated to navigating these procedural nuances at the Supreme Court of India.

The firm specializes in:

- Supreme Court Litigation: Transfer Petitions (Civil & Criminal), Special Leave Petitions (SLP), and Writ Petitions.

- Matrimonial Disputes: Handling complex divorce transfers, child custody battles, and mediation settlements.

- Criminal Defense: Seeking transfer of trials in cases of political vendetta or threat to life.

- Corporate Litigation: Resolving jurisdictional disputes and cross-suits.

Patra’s Law Chambers maintains a robust presence in both the national capital and the eastern metropolis, ensuring seamless representation for clients across jurisdictions.

Contact Information:

If you want to get a consultation regarding any Supreme Court matter, you can click here.

(Note: Clients are advised to refer to the official firm website for the most current street addresses and consultation appointment numbers.)

(Note: Clients are advised to refer to the official firm website for the most current street addresses and consultation appointment numbers.)

Key Precedents Cited

- Mona Aresh Goel v. Aresh Satya Goel (2000) 9 SCC 255: Established the “wife’s convenience” principle.

- Santhini v. Vijaya Venketesh (2017) SCC OnLine SC 1213: Ruled on the limitations of Video Conferencing in transfer matters.

- Shilpa Sailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan (2023): Constitution Bench ruling on Article 142 divorce powers.

- Mohammad Shahabuddin v. State of Bihar (2017): Landmark criminal transfer for witness safety.

- B.R. Ambedkar College of Law v. Union of India (1993): Scope of Section 25 jurisdiction.

Works cited

- Transfer Petitions Under Section 25 of the Civil Procedure Code in Matrimonial Disputes: A Detailed Overview – P A & Partners- Advocates & Solicitors, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.palawpartners.com/transfer-petitions-under-section-25-of-the-civil-procedure-code-in-matrimonial-disputes-a-detailed-overview/

- Section 25 – India Code, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_3_20_00051_190805_1523340333624§ionId=33359§ionno=25&orderno=26

- Explained| Inter-State transfer of suit, appeal or other proceedings: Supreme Court’s power under Section 25 CPC versus Common High Courts’ power under Section 24 CPC – SCC Online, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/03/13/section-24-25-cpc-transfer-suit-appeal-other-proceedings-common-high-court-gauhati-nagaland-supreme-court-power-inter-state-transfer-scope-legal-explainer-updates-research-news/

- Transfer of Criminal Cases Under BNSS | PDF | Magistrate | Judge – Scribd, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/857128444/Transfer-of-Criminal-Cases-Under-BNSS

- Transfer Of Criminal Cases – Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://bharatiyanagariksurakshasanhita.com/transfer-of-criminal-cases/

- vlk/kkj.k izkf/kdkj ls izdkf’kr PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY lañ 54] ubZ fnYyh] lkse okj] fnlEcj 25] 2023@ikS”k 4] 1945 ¼’kd – Ministry of Home Affairs, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/2024-04/250884_2_english_01042024.pdf

- power of supreme court to transfer cases and appeals, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://acadpubl.eu/hub/2018-120-5/3/234.pdf

- Trials can be transferred only in exceptional cases: Supreme Court – The Hindu, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ongoing-criminal-trials-can-be-transferred-only-in-exceptional-circumstances-supreme-court/article66714701.ece

- SC shifts don to Tihar jail – Telegraph India, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/sc-shifts-don-to-tihar-jail/cid/1497894

- SC reserves order on plea to transfer Shahabuddin from Siwan jail – The Economic Times, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://m.economictimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/sc-reserves-order-on-plea-to-transfer-shahabuddin-from-siwan-jail/articleshow/56626639.cms

- SK MD ANISUR RAHAMAN v. THE STATE OF WEST BENGAL | Supreme Court Of India | Judgment – CaseMine, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/6926f340a5e87444f39c77dd

- Supreme Court refuses to transfer murder trial outside West Bengal – SCC Online, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/04/03/supreme-court-refuses-to-transfer-murder-trial-outside-west-bengal-legal-research-legal-news-updates/

- Section 25 CPC – Supreme Court’s Authority to Transfer Suits – ILMS Academy, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.ilms.academy/blog/section-25-cpc-supreme-court-authority-transfer-suits

- Transfer of Criminal Cases must Emphasise Fair Trial, not Inconvenience – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/transfer-of-criminal-cases-must-emphasise-fair-trial-not-inconvenience-shri-senthur-agro-and-oil-industries-v-kotak-mahindra-bank/

- Transfer petition in the Supreme Court of India – iPleaders, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/transfer-petition-supreme-court-india/

- Santhini V. Vijaya Venketesh: The Concept Of Video Conferencing In Matrimonial Disputes, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.ijllr.com/post/santhini-v-vijaya-venketesh-the-concept-of-video-conferencing-in-matrimonial-disputes

- Santhini Versus Vijay Venkatesh – Shonee Kapoor, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.shoneekapoor.com/santhini-versus-vijay-venkatesh/

- SANTHINI Vs. VIJAYA VENKETESH | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/SANTHINI%20Vs%28DOT%29%20VIJAYA%20VENKETESH

- “A delay tactic”; Bombay High Court rejects wife’s transfer plea in divorce proceedings, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/08/07/bom-hc-denies-transfer-in-divorce-case-over-delay-tactics/

- SC’s Power To Directly Grant Divorce: Judgement in Plain English, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/reports/divorce-under-article-142-judgement-in-plain-english/

- Supreme Court Grants Divorce by Invoking Article 142 in a Transfer Petition – Legal Light Consulting – Leading Law Firm in India, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://legallightconsulting.com/supreme-court-grants-divorce-by-invoking-article-142-in-a-transfer-petition/

- J U D G M E N T – Supreme Court of India, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2014/26304/26304_2014_2_1501_44203_Judgement_01-May-2023.pdf

- Supreme Court Rules, 2013 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/45279932/

- Supreme Court Rules, 2013.pdf, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://thc.nic.in/Central%20Governmental%20Rules/Supreme%20Court%20Rules,%202013.pdf

- Birmingham Support Enforcement Lawyer | Contempt Proceeding – Riley Law Firm, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.rileylawfirm.net/divorce/petitions-to-modify/contempt-proceedings/

- IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION TRANSFER PETITION (C) NO. 2922 OF 2024 XXX … PETITIONER Versus YYY, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.sci.gov.in/sci-get-pdf/?diary_no=479302024&type=o&order_date=2025-03-20&from=latest_judgements_order

- Transfer of certain cases. – Constitution of India, accessed on December 26, 2025, http://constitutionofindia.etal.in/article_139a/

- Article 139A: Transfer of certain cases – Constitution of India, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.constitutionofindia.net/articles/article-139a-transfer-of-certain-cases/

- Applications for Transfer Under Article 139A(2) of the Constitution – Legal Light Consulting – Leading Law Firm in India, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://legallightconsulting.com/applications-for-transfer-under-article-139a2-of-the-constitution/

- Court Revisits Transfer Power Under Article 139A – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/court-revisits-transfer-power-under-article-139a/

- Procedures, Grounds & Judgements To Transfer Case In India – Advocate Kapil Chandna, accessed on December 26, 2025, https://kapilchandna.legal/procedures-grounds-judgements-to-transfer-case-in-india/