- BNSS 2023 replaces CrPC; Section 35 corresponds to CrPC Section 41 and embeds arrest limitations.

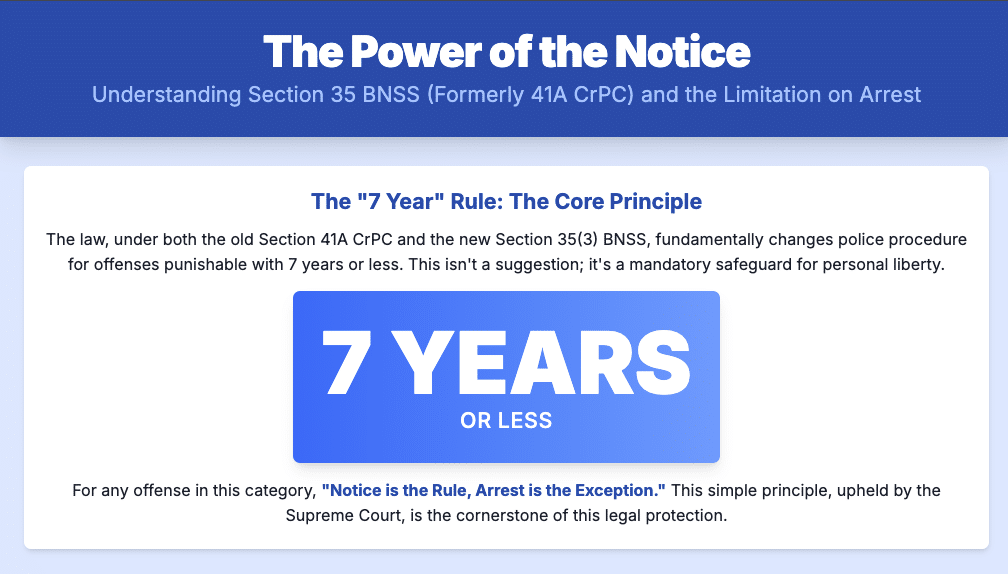

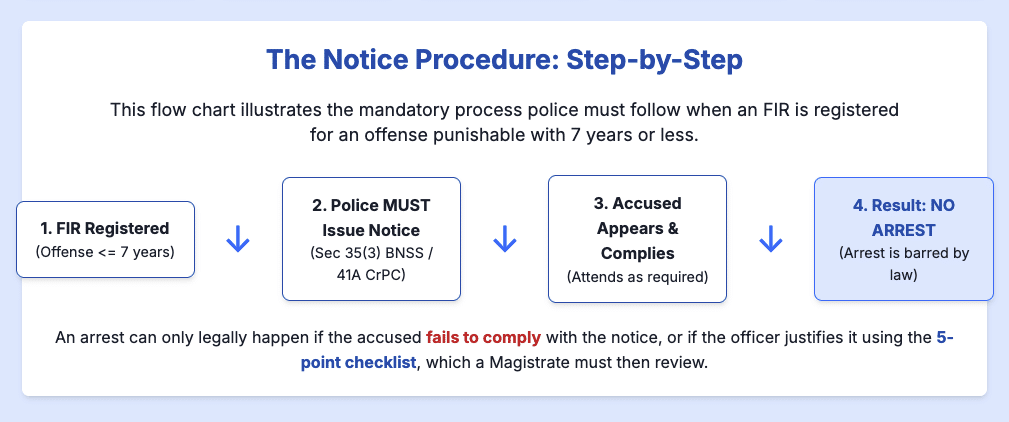

- Section 35(3) BNSS incorporates the Section 41A notice — notice of appearance is default, arrest is exception.

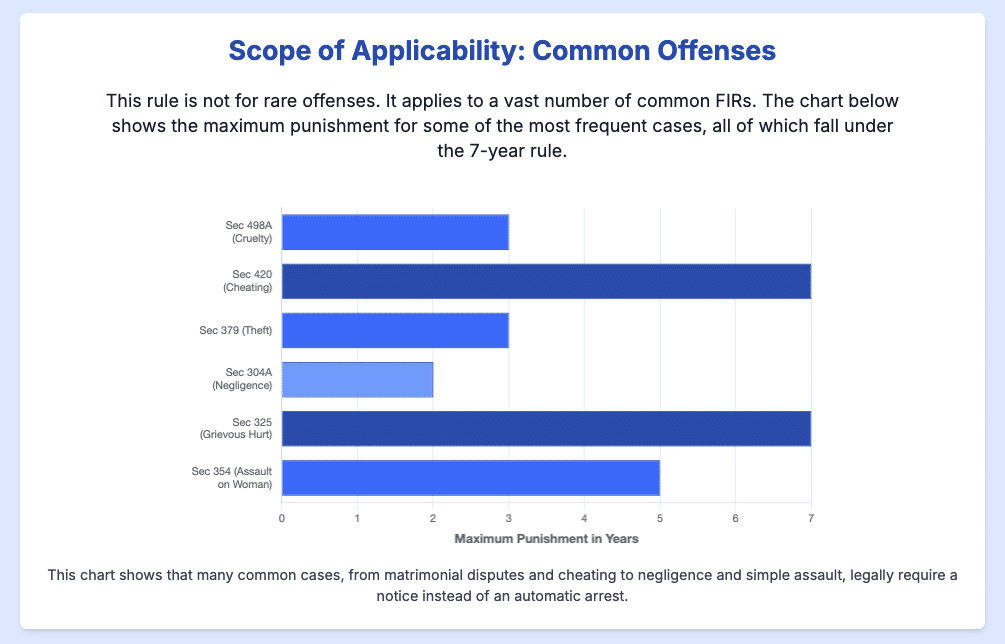

- Notice applies to offenses with maximum punishment of ≤7 years; common examples include theft, cheating, simple hurt.

- Arnesh Kumar (2014) made issuance of the notice mandatory; police must record written reasons for arrest or non-arrest.

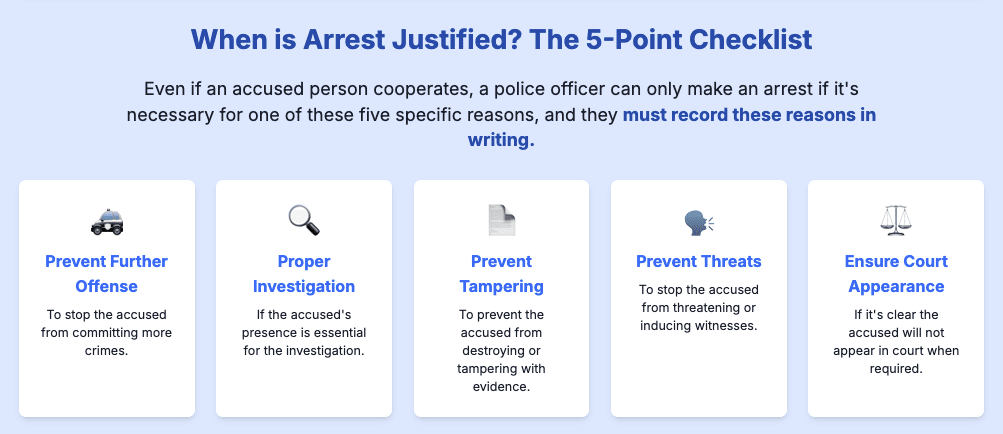

- Police can arrest only with recorded "reason to believe" for specific purposes (prevent offense, investigation, tampering, witness threat, court presence).

- Non-compliance leads to remedies: bail, departmental action, contempt, and judicial quashing of illegal arrests.

- Transition emphasizes liberty: Section 35 strengthens judicial safeguards so arrest is a last resort, not routine procedure.

A Complete guide to police notice: Correlating Section 41A CrPC with Section 35 BNSS

-

Creditor and contributor of this article:

Patra’s Law Chambers:

About Us:

Patra’s Law Chambers is a law firm with offices in Kolkata & Delhi, offering comprehensive legal services across various domains. Established in 2020 by Advocate Sudip Patra (Advocate, Supreme Court of India & Calcutta High Court) an alumnus of the Prestigious Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, IIT Kharagpur ,with Post Graduate diploma in Business Law from IIM Calcutta, the firm specializes in Civil, Criminal, Writs,High Court Matters, Trademark, Copyright, Company, Tax, Banking, Property disputes, Service law, Family law, and Supreme Court matters.You can know more about us in here

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid

Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +91 890 222 4444/ +91 7003 715 325

1. Introduction: The Evolution from CrPC to BNSS

The Indian criminal justice system is undergoing a foundational shift with the introduction of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023, which is set to replace the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973. A critical area of this legislative evolution concerns the police’s power to arrest and the procedural safeguards protecting individual liberty.

A cornerstone of these safeguards under the CrPC is Section 41A, which mandates a “Notice of appearance” in lieu of arrest for specific offenses. The user’s query regarding Section 35 and its correlation with Section 41A strikes at the heart of this change.

To clarify:

- Section 41 of CrPC outlines when police may arrest without a warrant.

- Section 41A of CrPC acts as a limitation on that power, mandating a notice for offenses punishable with 7 years or less.

- Section 35 of BNSS, 2023, is the new provision corresponding to Section 41 of CrPC.

- The principle of Section 41A (CrPC) has been directly incorporated into Section 35(3) of the BNSS.

This analysis provides a deep dive into the correlation between these provisions, the jurisprudence that shaped them, their practical applicability, and the landmark judgments that govern this field.

2. The Legislative Framework: CrPC vs. BNSS

The primary change is not one of spirit but of structure. The BNSS streamlines the provisions, making the limitation on arrest (the 41A notice) an integral part of the section on arrest powers, rather than a separate section.

| Provision | Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) | Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) |

| Power to Arrest | Section 41: “When police may arrest without warrant.” Lists conditions (e.g., cognizable offense in presence, credible information, reasonable suspicion). | Section 35: “When police may arrest without warrant.” Largely retains the same conditions as Sec 41, CrPC. |

| Notice in lieu of Arrest | Section 41A: “Notice of appearance before police officer.” This is a separate section detailing the procedure for offenses punishable with imprisonment for a term which may be less than 7 years or up to 7 years. | Section 35(3): This provision is embedded within the main arrest section. It directly corresponds to the old Sec 41A, CrPC. |

Key Correlation & Change:

The BNSS takes the mandate of Section 41A (CrPC) and makes it a subsection

$$Sec 35(3)$$

of the primary power to arrest (Sec 35). This structural change emphasizes that the notice is the default rule, and arrest is the exception that must be justified. The “Section 35 Notice” under BNSS is the new “41A Notice.”

3. The Law and Jurisprudence: Why the Notice Exists

The provision for a notice of appearance was introduced via the CrPC (Amendment) Act, 2008 (effective 2010). The legislative intent, bolstered by judicial pronouncements, was to address several key issues:

- Overcrowded Jails: A significant portion of the jail population comprised undertrial prisoners, many arrested for minor offenses where pre-trial arrest was unnecessary.

- Protection of Liberty: To uphold the fundamental right to liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution, ensuring that arrest—a draconian measure—is not used mechanically.

- Preventing Harassment: To stop the police from using the power of arrest as a tool for harassment or extortion, especially in cases like matrimonial disputes (498A), minor scuffles, or cheating.

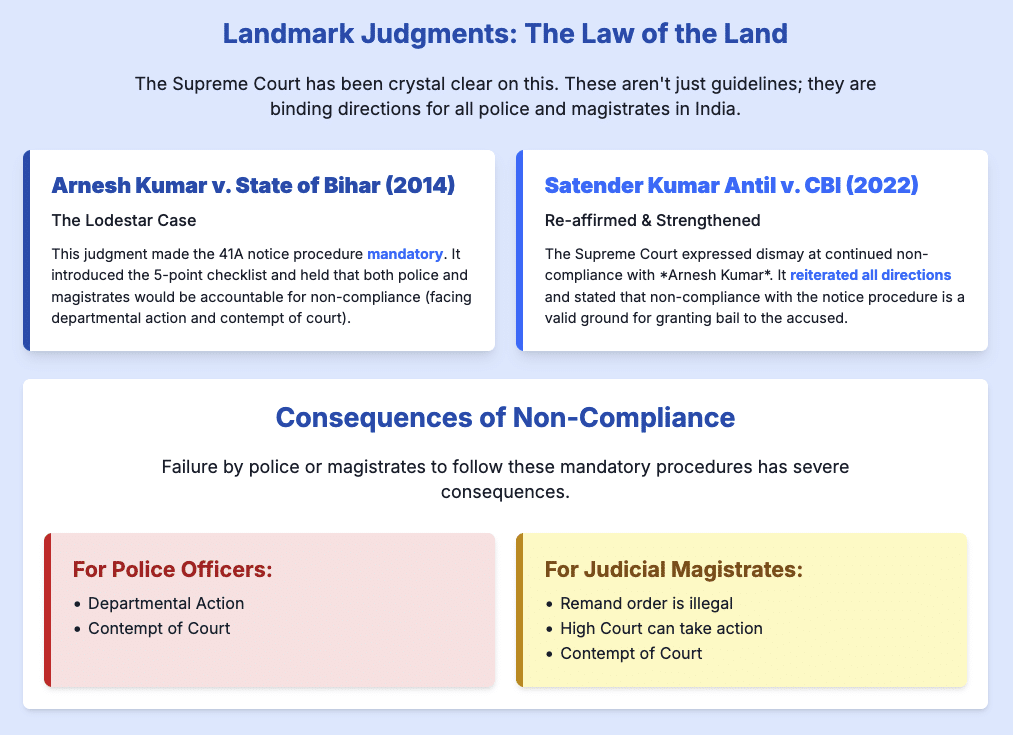

The jurisprudence was famously cemented by the Supreme Court in Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar** (2014)**. This judgment transformed Section 41A from a procedural guideline into a mandatory directive.

The Mandate of Arnesh Kumar (Governing both 41A CrPC & 35 BNSS):

The Supreme Court, observing rampant misuse of arrest powers, laid down binding directions:

- Mandatory Notice: For any offense punishable with imprisonment of 7 years or less (with or without a fine), the police must issue a notice of appearance (under Sec 41A CrPC / Sec 35(3) BNSS) to the accused.

- No Automatic Arrest: The accused shall not be arrested if they comply with the notice and continue to appear as required.

- Justification for Arrest: A police officer can only arrest if they have “reason to believe” that such arrest is necessary for specific, recorded reasons (the “Section 41(1)(b)(ii) checklist” in CrPC, now in Sec 35(1) BNSS):

- To prevent the accused from committing any further offense.

- For proper investigation of the offense.

- To prevent the accused from tampering with evidence.

- To prevent the accused from threatening or inducing any witness.

- To ensure the accused’s presence in court when required.

- Written Reasons: The officer must record these reasons in writing. If they decide not to arrest, that reason must also be recorded.

- Judicial Scrutiny: The Magistrate, when authorizing detention, must scrutinize the police report and be satisfied that the arrest is justified based on these recorded reasons.

- Consequences of Non-Compliance (by Police): Failure to comply with these directions would make the police officer liable for departmental action and contempt of court.

4. Applicability: 20 Common Scenarios for a Notice (Section 35 BNSS / 41A CrPC)

A notice under Section 35(3) BNSS (formerly 41A CrPC) is the standard procedure in all cases where the maximum punishment is imprisonment for 7 years or less. This applies to a vast number of FIRs.

Here are 20 common offenses

$$with corresponding old IPC and new BNS (Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) sections$$

where such a notice is mandatory:

- Cruelty by Husband/Relatives (Sec 498A IPC / Sec 84 BNS): The Arnesh Kumar case itself arose from this, making it the classic example. (Punishment: 3 years).

- Theft (Sec 379 IPC / Sec 301 BNS): Simple theft. (Punishment: 3 years).

- Cheating (Sec 420 IPC / Sec 316 BNS): Many white-collar and financial disputes. (Punishment: 7 years).

- ): (Punishment: 3 years).

- Rash and Negligent Driving (Sec 279 IPC / Sec 106(1) BNS): Common in accident cases. (Punishment: 6 months).

- Causing Death by Negligence (Sec 304A IPC / Sec 106(2) BNS): (Punishment: 2 years, though note BNS has a separate provision for “hit and run”).

- Simple Hurt (Sec 323 IPC / Sec 113 BNS): (Punishment: 1 year).

- Grievous Hurt (Sec 325 IPC / Sec 114 BNS): (Punishment: 7 years).

- Wrongful Restraint (Sec 341 IPC / Sec 136 BNS): (Punishment: 1 month).

- Assault on a Woman to Outrage Modesty (Sec 354 IPC / Sec 73 BNS): (Punishment: 1-5 years).

- Stalking (Sec 354D IPC / Sec 77 BNS): (Punishment: 3-5 years).

- Defamation (Sec 499/500 IPC / Sec 354 BNS): (Punishment: 2 years).

- Criminal Intimidation (Sec 506 IPC / Sec 350 BNS): (Punishment: 2 years, or 7 if threat is severe).

- Insult to Modesty of a Woman (Sec 509 IPC / Sec 78 BNS): (Punishment: 3 years).

- Mischief (Sec 427 IPC / Sec 322 BNS): Causing damage to property. (Punishment: 2 years).

- House Trespass (Sec 448 IPC / Sec 328 BNS): (Punishment: 1 year).

- Rioting (Sec 147 IPC / Sec 187 BNS): (Punishment: 2 years).

- Affray (Sec 160 IPC / Sec 190 BNS): (Punishment: 1 month).

- Negligent Conduct with Fire (Sec 285 IPC): (Punishment: 6 months).

- Adulteration of Food/Drink (Sec 272 IPC): (Punishment: 6 months).

In all these scenarios, filing an FIR does not automatically give police the power to arrest. They must first issue a Section 35(3) BNSS notice.

5. Landmark Judgments on Section 41A CrPC (Applicable to Sec 35 BNSS)

The following table outlines the key judgments that have shaped the law on arrest and the necessity of a 41A notice.

| Case Citation | Court | Key Principle / Ratio Decidendi |

| Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar** (2014) 8 SCC 273** | Supreme Court | The lodestar case. Made issuance of Sec 41A notice mandatory for offenses with punishment <= 7 years. Linked police and magistrate accountability to this process. |

| Satender Kumar Antil v. CBI** (2022) 10 SCC 51** | Supreme Court | Re-affirmed and strengthened Arnesh Kumar. Directed creation of “Bail Acts.” Held that non-compliance with 41A is a valid ground for granting anticipatory or regular bail. |

| Siddharth v. State of U.P.** (2022) 1 SCC 676** | Supreme Court | Held that arrest is not required even when a chargesheet is filed. If 41A was complied with during investigation, the accused does not need to be taken into custody at the time of chargesheeting. |

| Md. Asfak Alam v. State of Jharkhand** (2023) SCC OnLine SC 892** | Supreme Court | Recently reiterated the Arnesh Kumar guidelines, expressing dismay at continued non-compliance by police and lower judiciary. Emphasized that 41A is not a mere formality. |

| Joginder Kumar v. State of U.P.** (1994) 4 SCC 260** | Supreme Court | A precursor to 41A. Held that arrest is not a must in every cognizable case. An arrest should not be made in a routine manner; it must be justified. |

| D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal** (1997) 1 SCC 416** | Supreme Court | Laid down 11 mandatory guidelines for police to follow during arrest and detention to protect the fundamental rights of the arrestee. (This is related to the procedure of arrest). |

| Rini Johar v. State of M.P.** (2016) 11 SCC 703** | Supreme Court | Awarded compensation to individuals who were illegally arrested in violation of Section 41A, holding the state vicariously liable. |

| Amandeep Singh Johar v. State of NCT of Delhi** (2018) SCC OnLine Del 6679** | Delhi High Court | Issued detailed “checklists” and “standing orders” for Delhi Police to ensure strict compliance with Section 41A procedures. |

| Social Action Forum for Manav Adhikar v. Union of India** (2018) 10 SCC 443** | Supreme Court | While dealing with 498A, it reinforced the Arnesh Kumar guidelines and struck down automatic arrests. |

| M.C. Abraham v. State of Maharashtra** (2003) 2 SCC 649** | Supreme Court | Held that police are not bound to arrest a person simply because they are an accused in a cognizable offense, even if they have the power to do so. |

| Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of U.P.** (2014) 2 SCC 1** | Supreme Court | While about mandatory FIR registration, it’s relevant as the 41A procedure kicks in after the FIR is registered and the investigation begins. |

| Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab** (1980) 2 SCC 565** | Supreme Court | The constitutional bench judgment on anticipatory bail (438 CrPC). Non-issuance of a 41A notice is a strong ground for seeking anticipatory bail. |

| V.S. Krishnan v. State of T.N.** (2021) SCC OnLine Mad 2120** | Madras High Court | Clearly stated that any remand by a Magistrate without ensuring 41A compliance is illegal and violates Article 21. |

| Rajesh Sharma v. State of U.P.** (2018) 10 SCC 472** | Supreme Court | (Though later modified) This judgment (related to 498A) also discussed measures to prevent precipitative arrests, reinforcing the 41A framework. |

| Bhupinder Singh v. Union of India** (2011) 124 DRJ 545** | Delhi High Court | Discussed the legislative intent behind the 2008/2010 amendments (introducing 41A), stating it was to protect citizens from humiliation and harassment. |

| Pala Ram v. State of Haryana** (2019) SCC OnLine P&H 764** | P&H High Court | Granted anticipatory bail noting that the police had failed to follow the 41A procedure before attempting to arrest the accused. |

| Arvind Kumar v. State** (2021) SCC OnLine Del 3442** | Delhi High Court | Discussed the validity of serving a 41A notice through electronic means like WhatsApp, recognizing modern communication methods. |

| Nikesh Tarachand Shah v. Union of India** (2018) 11 SCC 1** | Supreme Court | A landmark judgment on bail (though under PMLA), it strongly affirmed that ‘liberty is the norm and jail is the exception.’ This principle is the foundation of Sec 41A. |

| Mehale & Ors v. State of Karnataka** (2020) SCC OnLine Kar 3058** | Karnataka High Court | Quashed criminal proceedings that were initiated after an illegal arrest was made in gross violation of 41A, showing severe consequences for non-compliance. |

| Srikanth v. State of Telangana** (2019) SCC OnLine TS 1238** | Telangana High Court | Issued specific directions to all police stations and Magistrates in the state to strictly implement the Arnesh Kumar guidelines. |

6. Conclusion

The transition from Section 41A of the CrPC to Section 35(3) of the BNSS is a positive legislative reinforcement of judicial wisdom. By embedding the “notice of appearance” directly into the section governing the power to arrest, the law now more clearly and forcefully communicates that arrest is the last resort, not the first step.

For any person named in an FIR for an offense punishable with 7 years or less, the “Section 35 Notice” is a legal right. Compliance with this notice is the surest way to avoid pre-trial detention, and non-compliance by the police is a serious procedural lapse that can be grounds for bail, departmental action, and even contempt of court. This provision is a critical safeguard for the liberty of the common citizen against the arbitrary exercise of state power.

Disclaimer: This write-up is for informational and academic purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For specific legal issues, please consult with a qualified legal professional.

A Research Publication by:

Patra’s Law Chambers

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First FSection 35 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhitaloor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Section 35 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita_watermarkPhone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044