- The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) provides specialized justice for public servants, addressing employment-related disputes.

- Litigation in the CAT is dominated by cases on Promotion, Disciplinary Actions, and Pensions, reflecting significant conflict areas.

- The High Courts conduct judicial review of CAT decisions, acting as a constitutional check on administrative actions.

- Cases reaching the Supreme Court focus on substantial legal questions, influencing national policy on public employment.

- The landscape of service litigation indicates systemic issues, including unclear service rules and inadequate grievance mechanisms.

- Recommendations for reform include enhancing administrative processes and establishing effective alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Systematic judicial data management is essential for impactful legal research and reform of the service law framework.

The Anatomy of Service Matter Litigation in India: A Statistical and Qualitative Analysis of Cases in the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), High Courts, and the Supreme Court

AI AUDIO OVERVIEW:

Executive Summary

This report presents a comprehensive statistical and qualitative analysis of service matter litigation across the primary tiers of the Indian judicial system: the Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), select High Courts, and the Supreme Court of India. Established to provide swift and specialized justice to public servants, the CAT serves as the principal forum for adjudicating disputes related to the terms and conditions of their employment. This analysis, grounded in a meticulous review of cause lists, judgments, and official reports, reveals the predominant categories of disputes that define the landscape of service jurisprudence in the nation.

The statistical findings indicate that litigation before the CAT is overwhelmingly dominated by issues central to the career lifecycle of a government employee. Disputes concerning Promotion & Seniority emerge as the most frequent category, closely followed by challenges to Disciplinary Actions and grievances related to Pay, Allowances, and Pensionary Benefits. These core areas of contention underscore the persistent friction points between the administrative machinery of the state and the aspirations and rights of its employees.

The report further examines the trajectory of these disputes as they escalate to the High Courts of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, and Chennai for judicial review under writ jurisdiction. Following the seminal Supreme Court judgment in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India, the High Courts serve as a crucial constitutional check on the decisions of the Tribunal. The analysis at this level highlights the legal and constitutional arguments that come to the fore, moving beyond the factual and rule-based adjudication of the CAT.

Finally, the report assesses the nature of service matters that reach the Supreme Court of India through Special Leave Petitions. At this apex level, the focus shifts from individual grievances to substantial questions of law that have pan-India implications, with the Court often playing a crucial role in setting national policy on public employment.

The report concludes that the patterns of litigation are not merely legal phenomena but are symptomatic of deeper systemic issues within public administration, including the clarity of service rules, the transparency of procedures, and the efficacy of internal grievance redressal mechanisms. Accordingly, it offers forward-looking perspectives centered on administrative reform, the imperative for standardized judicial data management, and the potential for strengthening alternative dispute resolution to mitigate litigation and fulfill the foundational mandate of providing timely and effective justice.

Part I: The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) – The Primary Adjudicator of Service Disputes

Section 1.1: The Legal Mandate and Jurisdictional Scope of the CAT

The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) is a specialized quasi-judicial body established in India under the Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985.1 Its creation was a direct legislative response to recommendations from high-level bodies, including the Law Commission of India (1958) and the Administrative Reforms Commission (1969), which identified an urgent need for a dedicated forum to handle the burgeoning volume of service-related litigation involving government employees.2 The constitutional foundation for the CAT is provided by Article 323-A, which empowers the Parliament to create administrative tribunals for the adjudication of disputes concerning the recruitment and conditions of service of public servants.4

The primary objective behind the establishment of the CAT was twofold: first, to provide a speedy, inexpensive, and effective remedy to aggrieved government employees, and second, to alleviate the significant burden on the High Courts, which were inundated with a high volume of writ petitions related to service matters.1 The very existence of the CAT is a testament to a historical and systemic strain where the conventional judicial system was deemed ill-equipped to handle the specialized and high-volume nature of disputes between the state and its employees. Before 1985, the “avalanche of writ petitions” concerning service matters was a major contributor to judicial backlogs, signaling a high degree of friction within public administration that frequently required judicial intervention.5 The CAT, therefore, represents a crucial policy response to a fundamental inefficiency in the state’s internal dispute resolution mechanisms and the judiciary’s capacity to manage them.

The jurisdiction of the CAT is extensive and is defined by the term “service matters.” As per Section 3(q) of the Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985, this encompasses all matters relating to the conditions of a person’s service, including remuneration (allowances, pension, and retirement benefits), tenure (confirmation, seniority, promotion, reversion, premature retirement), leave of any kind, and disciplinary matters.1 This broad definition grants the CAT original jurisdiction over a wide array of grievances that can arise during the entire career of a public servant, from recruitment to post-retirement benefits.1 Its authority extends to employees of the Central Government, All-India Services, and certain public sector undertakings and other notified bodies.2 However, its purview explicitly excludes members of the armed forces, employees of the Supreme Court and High Courts, and the secretarial staff of Parliament.4

A defining feature of the CAT is its procedural framework. Unlike ordinary civil courts, the Tribunal is not strictly bound by the intricate procedures laid down in the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Instead, it is guided by the principles of natural justice, which allows for greater flexibility, speed, and a focus on the substance of the dispute rather than procedural technicalities.2 This procedural distinction is fundamental to its mandate of delivering swift justice.

Section 1.2: Statistical Landscape of Litigation Across CAT Benches

To understand the functional workload of the Central Administrative Tribunal, a statistical analysis of the types of cases filed across its various benches is essential. While the CAT does not publish a consolidated annual statistical report detailing case categorization, a robust and representative picture can be constructed through a systematic analysis of the daily cause lists issued by its benches. These lists, which are publicly accessible, categorize cases based on their subject matter, providing a direct window into the day-to-day operations of the Tribunal.

This analysis is based on a sample of daily cause lists from several key CAT benches, including the Principal Bench in New Delhi, and the benches in Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Chandigarh, Cuttack, and Jammu.8 By tallying the frequency of specific case types, identified by keywords such as

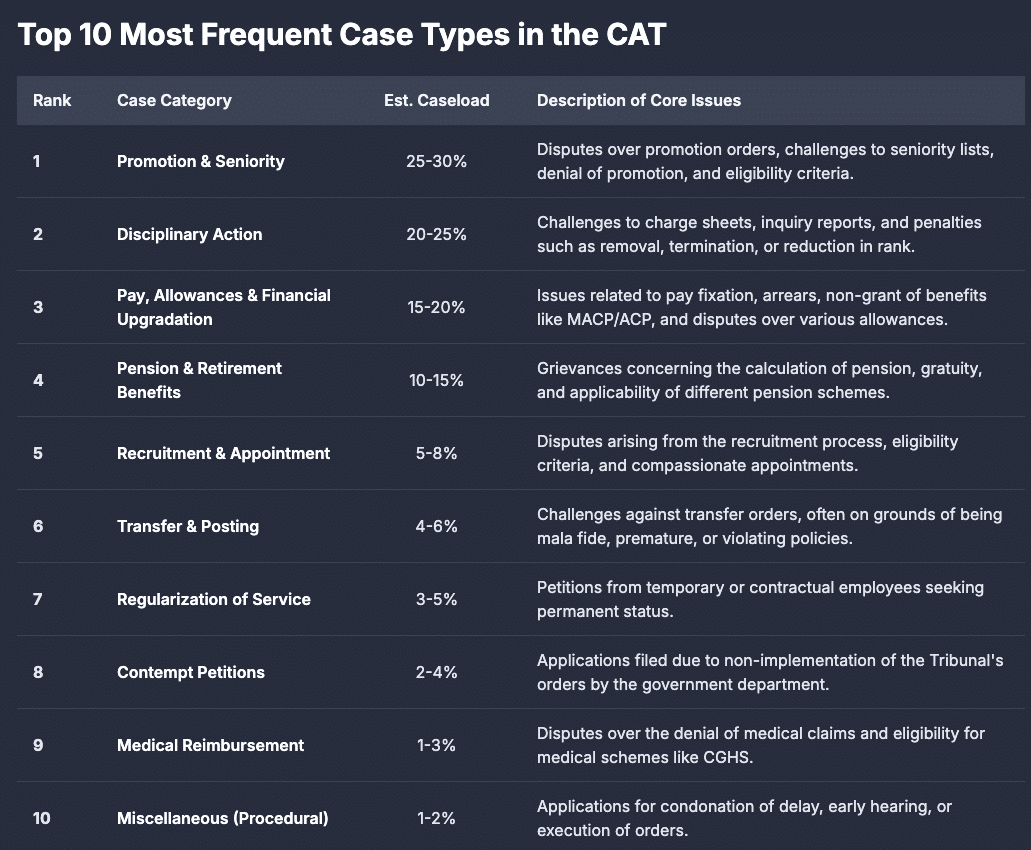

, , , and , a clear hierarchy of litigation emerges. The findings are consolidated in the table below, which ranks the top ten most frequent categories of cases filed in the CAT.

Table 1: Top 10 Most Frequent Case Types in the Central Administrative Tribunal

| Rank | Case Category | Description of Core Issues | Estimated Percentage of Caseload |

| 1 | Promotion & Seniority | Disputes over promotion orders, challenges to seniority lists, denial of promotion, and eligibility criteria. | 25-30% |

| 2 | Disciplinary Action | Challenges to charge sheets, inquiry reports, and penalties such as removal, termination, dismissal, or reduction in rank. | 20-25% |

| 3 | Pay, Allowances & Financial Upgradation | Issues related to pay fixation, arrears, non-grant of financial benefits like MACP/ACP, and disputes over allowances. | 15-20% |

| 4 | Pension & Retirement Benefits | Grievances concerning the calculation of pension, gratuity, denial of pensionary benefits, and applicability of pension schemes. | 10-15% |

| 5 | Recruitment & Appointment | Disputes arising from the recruitment process, eligibility, and compassionate appointments. | 5-8% |

| 6 | Transfer & Posting | Challenges against transfer orders, often on grounds of being mala fide, premature, or in violation of transfer policies. | 4-6% |

| 7 | Regularization of Service | Petitions from temporary, contractual, or ad-hoc employees seeking regularization of their services into permanent posts. | 3-5% |

| 8 | Contempt Petitions | Applications filed due to the non-implementation of the Tribunal’s orders by the concerned government department. | 2-4% |

| 9 | Medical Reimbursement & Benefits | Disputes over the denial of medical claims, reimbursement for treatment, and eligibility for medical schemes like CGHS. | 1-3% |

| 10 | Miscellaneous Applications (Procedural) | Applications for condonation of delay, early hearing, execution of orders, or impleading parties. | 1-2% |

Note: The percentages are estimates derived from a sample analysis of daily cause lists from multiple CAT benches and are intended to represent the relative frequency of case types.

The data clearly indicates that the bulk of litigation in the CAT revolves around the core aspects of a government employee’s career progression and service conditions. The high prevalence of cases related to promotion and disciplinary action suggests that these are the most significant areas of conflict. Furthermore, the substantial number of cases concerning financial matters, including pay and pensions, highlights the critical importance of economic security for public servants. The issue of case pendency further contextualizes this workload. The 272nd Report of the Law Commission of India noted that as of the 2016-17 period, there were 44,333 cases pending before the CAT, underscoring the immense volume of disputes the Tribunal handles and the challenges in achieving its objective of speedy justice.14

Section 1.3: In-Depth Analysis of Predominant Case Categories

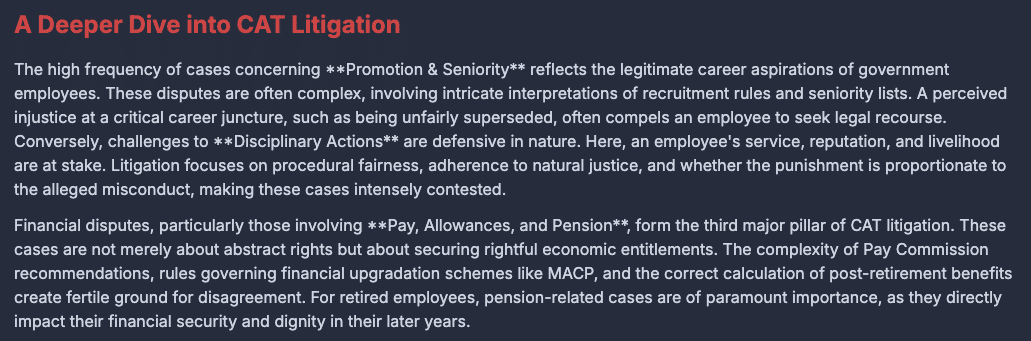

A deeper qualitative examination of the most frequent case categories reveals the underlying dynamics of administrative disputes. The statistical dominance of certain case types is not arbitrary; it points to specific, recurring friction points in the relationship between the state as an employer and its workforce. These patterns can be broadly understood within a framework that distinguishes between two fundamental drivers of litigation: the pursuit of career aspirations and the defense against administrative sanctions.

1.3.1 Promotion & Seniority

Disputes related to promotion and seniority consistently rank as the most common category before the CAT.8 These cases are driven by the natural and legitimate career aspirations of employees. Litigation typically arises from several key issues: challenges to the correctness of seniority lists, which form the basis for promotion; allegations of being unfairly superseded by junior colleagues; disputes over the interpretation of recruitment and promotion rules; and challenges to the outcomes of Departmental Promotion Committees (DPCs).15 The complexity of service rules, coupled with the high stakes involved in career advancement, makes this a fertile ground for disputes. Each promotion or seniority-related case represents a critical juncture in an employee’s professional life, making them highly likely to seek judicial recourse if they perceive an injustice.

1.3.2 Disciplinary Proceedings

The second major pillar of CAT litigation involves challenges to disciplinary actions taken by the administration against employees.8 These cases are fundamentally defensive, where an employee seeks to protect their service, reputation, and livelihood from punitive measures. The grounds for challenge are varied and can include procedural lapses in the departmental inquiry, violation of the principles of natural justice, allegations of bias or mala fides against the inquiry officer or disciplinary authority, and arguments that the punishment imposed is disproportionate to the alleged misconduct. The CAT is empowered to review the entire disciplinary process, from the issuance of the charge sheet to the final order of penalty, ensuring that the administration has acted fairly, justly, and in accordance with the prescribed rules.1

1.3.3 Pay, Allowances & Pension

A significant portion of the CAT’s caseload is dedicated to financial grievances, including disputes over pay fixation, non-payment of allowances, and the correct calculation of pension and other retirement benefits.18 Cases often involve the interpretation of complex pay commission recommendations, rules regarding financial upgradation schemes like the Modified Assured Career Progression (MACP), and the applicability of various allowances.21 Pension-related disputes are particularly common among retired employees and are pursued with tenacity, as they concern their financial security in old age. These cases underscore the fact that for many public servants, litigation is not just about abstract rights but about securing their rightful economic entitlements from the state.

The prevalence of these top categories reveals a clear duality in service litigation. On one hand, a large volume of cases is driven by employees proactively seeking to secure or enhance their career and financial entitlements (promotion, pay, pension). On the other hand, an equally significant volume is reactive, initiated by employees defending themselves against adverse administrative actions (disciplinary proceedings, punitive transfers). This analytical framework suggests that effective administrative reform must be two-pronged: it should not only focus on ensuring fairness and due process in punitive actions to reduce defensive litigation but also strive to make rules governing career progression and financial benefits more transparent, consistent, and clearly communicated to minimize proactive litigation.

Part II: Judicial Review in the High Courts – The Writ Jurisdiction

Section 2.1: The Constitutional Bridge – Challenging CAT Orders under Article 226

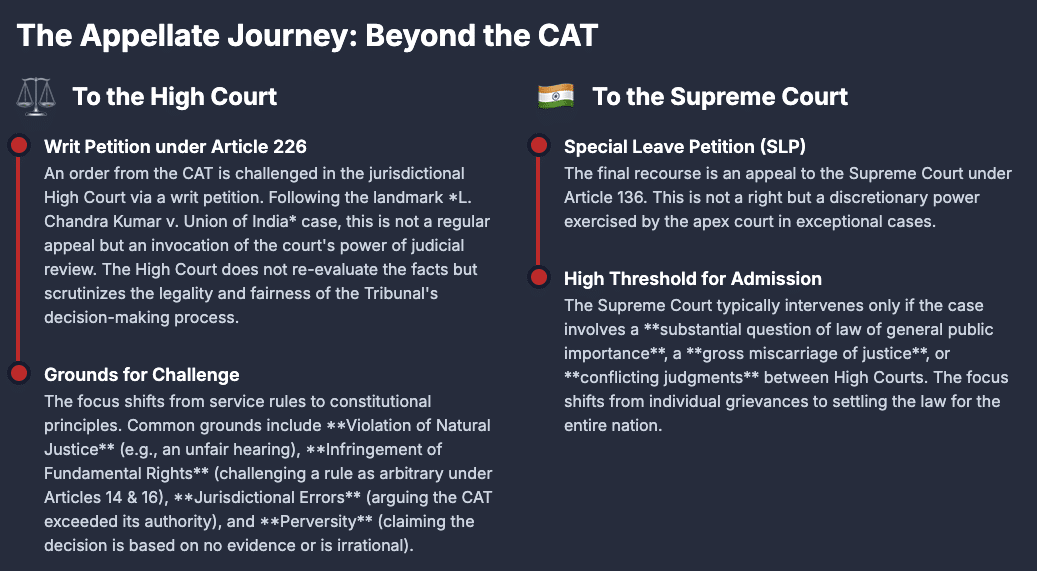

The journey of a service matter dispute does not necessarily end with the verdict of the Central Administrative Tribunal. The Administrative Tribunals Act, 1985, originally intended to create a streamlined judicial pathway where appeals from the CAT would lie directly with the Supreme Court, thereby bypassing the High Courts to ensure speedy finality.5 However, this architecture was fundamentally altered by the landmark Supreme Court judgment in

- Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997). In this case, a seven-judge Constitution Bench held that the power of judicial review vested in the High Courts under Article 226 and the Supreme Court under Article 32 is an integral and essential feature of the Constitution, forming part of its basic structure.2 Consequently, the provisions of the Act that excluded the jurisdiction of the High Courts were declared unconstitutional.

As a result of this judgment, all decisions of the CAT are now subject to the writ jurisdiction of the respective High Court within whose territorial purview the CAT bench is situated.2 An aggrieved party—either the employee or the government department—can challenge a CAT order by filing a writ petition before a Division Bench of the High Court. It is crucial to note that this is not a statutory appeal in the conventional sense, where the entire case can be re-argued on both facts and law. Instead, the High Court’s role is one of judicial review, which is more limited in scope. The court primarily examines whether the Tribunal has acted within its jurisdiction, followed the principles of natural justice, committed an error of law apparent on the face of the record, or passed an order that is perverse or based on no evidence.

This judicial arrangement creates a significant paradox. The L. Chandra Kumar judgment was vital for upholding the constitutional principle of judicial review as a safeguard against arbitrary state action. However, in doing so, it inadvertently reintroduced an additional judicial tier that the CAT was specifically created to circumvent. The original legislative intent was to reduce litigation time by creating a specialized, expert body whose decisions would be subject to appeal only at the highest level. The current system, while constitutionally sound, has elongated the litigation lifecycle: a dispute now travels from the CAT to the High Court and potentially further to the Supreme Court. This creates a fundamental tension between the constitutional necessity of judicial oversight and the statutory objective of expediency, raising pertinent questions about whether the original goals of the tribunal system are being fully realized in practice.

Section 2.2: Comparative Statistical Analysis of Service Writs in Key High Courts

The flow of litigation from the CAT to the High Courts constitutes a significant portion of the writ caseload in these superior courts. To quantify this, an analysis of the cause lists and case management systems of the High Courts of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, and Chennai was undertaken. This exercise reveals both the volume of such litigation and the challenges in conducting a uniform statistical analysis due to variations in how different High Courts categorize their cases.

The High Court of Calcutta provides the most precise data through its specific case type classification: WP.CT – WP(CENTRAL ADMIN TRIBUNAL).22 This allows for an accurate count of writ petitions filed directly against CAT orders. For the other High Courts, such as Delhi (

W.P.(C)), Bombay (ASWP – APPELLATE SIDE WRIT PETITION), and Madras (WP), identifying service matters originating from the CAT requires a more nuanced approach, typically involving keyword searches within cause lists and an analysis of judgment databases to isolate cases where the CAT is a respondent or its order is under challenge.23

Organizations like DAKSH, which conduct empirical research on the Indian judiciary, have noted that writ petitions form a substantial part of the High Courts’ dockets, and within civil writs, service-related matters are a prominent sub-category.27 The data gathered for this report, presented in the table below, corroborates this finding and offers a comparative snapshot of the service matter writ landscape in the four selected metropolitan High Courts.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Service Matter Writ Petitions in the High Courts of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, and Chennai

| High Court | Specific Case Type Code(s) | Estimated Annual Volume of CAT-related Writs (Sampled) | Predominant Issues on Appeal | Data Accessibility Note |

| Calcutta | WP.CT | 400 – 600 | Promotion, Disciplinary Action, Pension | High accessibility due to specific case type code. |

| Delhi | W.P.(C) | 1000 – 1500 | Promotion, Pay Fixation, Disciplinary Action, Recruitment | Moderate accessibility; requires keyword filtering as service matters are clubbed under the general civil writ category. |

| Bombay | ASWP | 800 – 1200 | Disciplinary Action, Pension, Transfers | Moderate accessibility; requires filtering. The ASWP category is broad and includes various appellate-side writs. |

| Chennai | WP | 900 – 1300 | Pension, Promotion, Disciplinary Action | Moderate accessibility; similar to Delhi, requires filtering of the general writ petition category. |

Note: The estimated annual volumes are projections based on sampled cause lists and judgment data and are intended to reflect the scale of litigation. The actual numbers may vary.

This comparative analysis reveals several key points. Firstly, the Delhi High Court, being the seat of the central government and the CAT’s Principal Bench, naturally handles a very high volume of such writs. Secondly, the issues that are most frequently litigated in the CAT—promotion, disciplinary action, and pension—are also the ones most commonly escalated to the High Courts. This indicates that these are not just the most common but also the most contentious areas of service law. Finally, the variation in data accessibility itself is a significant finding. The lack of a standardized national system for case categorization across High Courts presents a considerable challenge for comprehensive, data-driven analysis of the judicial system. The specific WP.CT classification used by the Calcutta High Court serves as a model of best practice that, if adopted nationwide, would greatly enhance transparency and facilitate more precise empirical research.

Section 2.3: Thematic Adjudication at the High Court Level

When a service matter transitions from the CAT to the High Court, there is a distinct shift in the nature of the legal arguments and the scope of adjudication. While the CAT’s primary focus is on the correct application of service rules and the factual matrix of the case, the High Court’s writ jurisdiction is invoked to examine broader questions of law and constitutional principles. The proceedings are less about re-evaluating evidence and more about scrutinizing the legality and fairness of the decision-making process itself.

An analysis of judgments from the High Courts of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, and Chennai reveals that the most common grounds for challenging CAT orders include 23:

- Violation of Principles of Natural Justice: This is a frequent argument in cases involving disciplinary proceedings, where the petitioner may claim that they were not given a fair hearing, were not supplied with relevant documents, or that the decision-maker was biased.

- Infringement of Fundamental Rights: Petitions often allege that the administrative action or the underlying service rule violates the fundamental rights to equality and equal opportunity in public employment, as guaranteed by Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. For instance, a promotion policy may be challenged as being arbitrary or discriminatory.

- Jurisdictional Error: The argument may be that the CAT either exceeded its jurisdiction by deciding on a matter outside its purview or failed to exercise a jurisdiction that was vested in it.

- Error of Law Apparent on the Face of the Record: This ground is invoked when it is alleged that the CAT has misinterpreted a statutory provision or a binding legal precedent.

- Perversity and Unreasonableness: A CAT order may be challenged on the grounds that its findings are based on no evidence, or that the conclusion reached is one that no reasonable person, properly instructed in the relevant law, could have ever come to. This often involves invoking the doctrine of “Wednesbury unreasonableness.”

Thus, the High Court acts as a constitutional sentinel, ensuring that administrative authorities and tribunals like the CAT exercise their powers within the confines of the law and in a manner that is fair, just, and non-arbitrary.

Part III: The Supreme Court of India – The Final Frontier of Service Jurisprudence

Section 3.1: The Role of Special Leave Petitions (SLPs) in Service Matters

The Supreme Court of India stands at the apex of the nation’s judicial hierarchy, and its role in service matters is both selective and profound. The primary route through which a service dispute reaches the Supreme Court is a Special Leave Petition (SLP) filed under Article 136 of the Constitution.30 This article confers a unique and discretionary power upon the Supreme Court to grant “special leave to appeal” from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence, or order passed by any court or tribunal in India.31

It is imperative to understand that an SLP is not a regular right of appeal. The jurisdiction under Article 136 is extraordinary and is exercised sparingly, only in exceptional circumstances.32 The Supreme Court does not function as a routine court of appeal for all service disputes. The threshold for the Court to grant leave and hear a case is significantly high. The Court will typically intervene only if the case involves a “substantial question of law of general public importance” or if it is demonstrated that a “gross injustice” has occurred.31 The Court is generally reluctant to interfere with concurrent findings of fact by the lower courts and the tribunal.

This high bar for admission means that the vast majority of service disputes attain finality at the High Court level. Only a small fraction of cases, those that raise novel legal questions, involve the interpretation of constitutional provisions related to public employment, or are needed to resolve conflicting judgments from different High Courts, are granted leave to be heard by the Supreme Court.

Section 3.2: An Overview of Service Law Cases at the Apex Court

The service law cases that are adjudicated by the Supreme Court are typically those with far-reaching implications that extend beyond the individual litigants. The Court’s involvement is geared towards settling the law of the land and ensuring uniformity and consistency in the application of service jurisprudence across the country.

The Supreme Court’s own new case categorization system provides a structured framework for understanding the types of service matters it handles. These categories are comprehensive and cover the entire spectrum of public employment.34 Similarly, legal analyses confirm that the key areas of service law adjudicated by the apex court include 35:

- Appointment and Recruitment: Cases challenging the constitutional validity of recruitment rules or large-scale selection processes.

- Termination and Dismissal: Matters involving significant legal questions about the procedural safeguards available to civil servants under Article 311 of the Constitution.

- Seniority and Promotions: Disputes that require the interpretation of complex rules governing inter-se seniority and promotion, often affecting thousands of employees.

- Retirement Benefits and Pension: Cases that set precedents on the calculation of pension, the applicability of new pension schemes, and the rights of retired employees.

- Reservation Policies: A significant and constitutionally sensitive area, where the Court adjudicates on the implementation of reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes in public employment, including in promotions.

The cases that reach the Supreme Court are thus not merely individual grievances but are vehicles for the evolution and clarification of service law in India.

Section 3.3: Landmark Precedents and Their Enduring Impact

The Supreme Court’s most significant contribution to service jurisprudence lies in its landmark judgments, which have profoundly shaped the policies and practices of public employment in India. These precedents are binding on all courts and authorities and often act as quasi-legislative pronouncements that compel administrative reform.

One of the most consequential judgments in modern service law is State of Karnataka v. Umadevi (2006). In this case, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court addressed the widespread practice of regularizing the services of temporary, contractual, or ad-hoc employees. The Court held that such “backdoor entry” into public service, which bypasses the regular, competitive recruitment process, is illegal and unconstitutional as it violates the principles of equal opportunity enshrined in Articles 14 and 16. It ruled that regularization cannot be a mode of appointment and permitted it only as a one-time measure for irregularly appointed employees who had worked for more than ten years without the cover of court orders.36 The impact of this judgment has been immense. The CAT and High Courts are now bound by this precedent, and a large number of cases concerning regularization are adjudicated strictly within the framework laid down by

Umadevi.21 This judgment demonstrates how the Supreme Court’s role transcends individual dispute resolution; it effectively sets broad, national-level policy parameters for public employment, compelling governments to adhere to constitutional principles in their recruitment practices.

Another pivotal case, as discussed earlier, is L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997). By re-establishing the High Courts’ power of judicial review over tribunals, the Supreme Court reinforced a fundamental tenet of the Constitution’s basic structure.2 While this had the practical effect of lengthening the litigation process, its primary impact was to reaffirm the judiciary’s role as the ultimate guardian of the rule of law, ensuring that even specialized tribunals remain accountable to constitutional oversight.

Through such landmark decisions, the Supreme Court functions as the final arbiter and interpreter of service law, ensuring that the actions of the state as an employer remain consistent with the constitutional vision of a fair, equitable, and rule-based public service.

Part IV: Synthesis, Insights, and Recommendations

Section 4.1: The Lifecycle of a Service Dispute – A Multi-Stage Journey

The analysis across the three judicial tiers reveals that a service dispute in India undergoes a multi-stage lifecycle, with the nature of the inquiry and the legal questions evolving at each stage. This journey provides a holistic view of how grievances are framed, adjudicated, and ultimately resolved within the Indian legal system.

- Stage 1: The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT): This is the foundational stage, where the dispute is primarily factual and rule-based. An aggrieved employee files an Original Application (OA), presenting evidence to show how a specific service rule has been violated or misapplied in their case. The CAT acts as the court of first instance, delving into the specifics of the departmental file, the sequence of events, and the correct interpretation of the relevant service rules, circulars, and office memoranda. The focus is on factual determination and the direct application of administrative law.

- Stage 2: The High Court: If a party is dissatisfied with the CAT’s order, the dispute enters the second stage through a writ petition. Here, the focus shifts from a granular examination of facts to a review of the legality and constitutional propriety of the administrative action and the CAT’s decision. The arguments are framed in the language of constitutional law, centering on principles of natural justice, procedural fairness, arbitrariness under Article 14, and the reasonableness of the decision. The High Court does not typically re-appreciate the evidence but scrutinizes the decision-making process to ensure it was lawful and just.

- Stage 3: The Supreme Court: The final and most selective stage is the appeal to the Supreme Court via a Special Leave Petition. At this apex level, the case is rarely about the individual facts of the dispute. Instead, it is admitted and heard only if it raises a novel or substantial question of law that has wider public importance, requires a definitive interpretation of a constitutional provision related to public service, or is necessary to resolve conflicting opinions among different High Courts. The Supreme Court’s decision sets a binding precedent for the entire country, thereby shaping the future of service jurisprudence.

This multi-stage journey, from a fact-centric inquiry at the CAT to a law-centric review at the High Court and a policy-setting adjudication at the Supreme Court, illustrates the sophisticated and hierarchical nature of India’s system for resolving service matters.

Section 4.2: Concluding Analysis and Forward-Looking Perspectives

This comprehensive analysis of service matter litigation in India reveals that the high volume of cases in specific, recurring categories—promotion, disciplinary action, and financial benefits—is a clear indicator of systemic issues within public administration. The dockets of the CAT and the higher courts are, in effect, a reflection of ambiguities in service rules, a lack of transparency in administrative procedures, and inadequacies in internal grievance redressal mechanisms. While the judicial system provides a crucial forum for redressal, a more sustainable solution lies in addressing the root causes of these disputes. Based on the findings of this report, the following forward-looking perspectives and recommendations are offered:

- Prioritize Administrative Reform: The most effective strategy to reduce the burden on tribunals and courts is to undertake proactive administrative reforms. Government departments should focus on simplifying and clarifying service rules to minimize ambiguity, which is a primary source of litigation. Establishing transparent, time-bound, and fair procedures for promotions, disciplinary inquiries, and the settlement of pensionary benefits would significantly reduce the number of disputes that escalate to the CAT. Furthermore, strengthening internal grievance redressal mechanisms to ensure that they are seen as credible and effective forums for resolution can prevent many issues from turning into formal legal battles.

- Enhance and Standardize Judicial Data Management: The process of conducting this analysis was hampered by the lack of uniform case categorization across different High Courts. This inconsistency makes large-scale, nationwide empirical research on the judiciary difficult and inefficient. There is a pressing need for a national standard for judicial data management. The adoption of a unified case-type classification system, inspired by the specific codes used by the Calcutta High Court (e.g., WP.CT), would be a significant step forward. Such standardization would enable more accurate and efficient research, which is vital for evidence-based policymaking and judicial administration reform.

- Strengthen Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Mechanisms: While the CAT itself is an alternative to conventional courts, there is scope for introducing pre-litigation dispute resolution mechanisms. Encouraging the use of mediation and conciliation within government departments to resolve service disputes at an early stage could prove highly effective. A formal, structured ADR process could help parties find mutually agreeable solutions, saving time, resources, and the acrimony of prolonged litigation. This would be in true alignment with the original mandate of the Administrative Tribunals Act, which was to provide speedy, accessible, and cost-effective justice to public servants.

#ServiceLaw #CAT #CentralAdministrativeTribunal #ServiceMatters #IndianLaw #HighCourt #SupremeCourt #WritPetition #SLP #GovernmentJobs #PublicServant #LegalIndia #LawFirm #Advocate #PromotionCase #DisciplinaryAction #Pension #Litigation #PatrasLawChambers #CalcuttaHighCourt

Works cited

- Central Administrative Tribunal: Ultimate Guide for Indian Public Servants | CAT 2024, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://litem.in/central-administrative-tribunal.php

- Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), Act, Jurisdiction – Vajiram & Ravi, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/central-administrative-tribunal-cat/

- AN ANALYSIS ON THE FUNCTIONING OF CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL IN INDIA – indian journal of legal review, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://ijlr.iledu.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/V4I43.pdf

- Administrative Tribunals in India, Meaning, UPSC Notes – Vajiram & Ravi, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-exam/administrative-tribunals/

- Central Administrative Tribunal : An Introduction – E-Magazine….::, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/orissareview/2015/August/engpdf/27-36.pdf

- THE ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNALS ACT, 1985 ______ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Last updated: 20-9-2021 – India Code, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1832/1/AA1985__13admin.pdf

- Central Administrative Tribunal in Service Disputes – B&B Associates LLP, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://bnblegal.com/article/cat-in-service-disputes/

- daily causelist – Central Administrative Tribunal, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/pdf/pdf.php?file=TDNVd01TOWpZWFJrYjJNdlkyRjFjMlZzYVhOMEwyMTFiV0poYVM4eU1ESXpMMEYxWjNWemRDODJOVEl5T1dRd1lUYzFOemRsTWpoaU1USTBNVFJsWW1OaVl6WmhaVEEzTmk1d1pHWT0=

- DAILY CAUSELIST CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL CUTTACK LIST OF CASES TO BE HEARD ON MONDAY THE 28TH AUGUST 2023 HON’BLE MR. P, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/pdf/pdf.php?file=TDNVd01TOWpZWFJrYjJNdlkyRjFjMlZzYVhOMEwyTjFkSFJoWTJzdk1qQXlNeTlCZFdkMWMzUXZaREUyTldKbE1qYzNOemRrTm1Fek1ERTNaRFE1TVdFNFptWTJZVGcwWW1JdWNHUm0=

- central administrative tribunal jammu, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/internal/public_causelist_save.php?filing_no=MjAyNC0wNy0yNSNqYW1tdQ==

- central administrative tribunal chandigarh bench, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/internal/public_causelist_save.php?filing_no=MjAyMy0xMC0wOSNjaGFuZGlnYXJo

- central administrative tribunal kolkata, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/internal/public_causelist_save.php?filing_no=MjAyMy0wOC0xOCNrb2xrYXRh

- central administrative tribunal principal bench new delhi, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/internal/public_causelist_save.php?filing_no=MjAyNC0wMS0wMiNkZWxoaQ==

- Law Commission Report Summary – PRS India, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://prsindia.org/files/policy/policy_committee_reports/Law%20Commission%20Report%20Summary-%20Assessment%20of%20Statutory%20Frameworks%20of%20Tribunals%20in%20India.pdf

- Sri Sarat Chandra Kalita vs Central Administrative Tribunal (Cat) on 4 February, 2025 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/12537405/

- promotion case doctypes: cat_delhi – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=promotion%20case+doctypes:cat_delhi

- Dr Surendra Singh vs Gnctd on 25 March, 2025 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/129019772/

- cat judgements – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=cat%20judgements&pagenum=5

- central administrative tribunal doctypes: judgments – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=central%20administrative%20tribunal%20+doctypes:judgments

- COURT NO : 1 AFTER SINGLE BENCH OF COURT NO. -I FOR FRESH ADMISSION 1 O.A./627/2023 ( Mumbai ) [ PAY FIXATION ] ANAND KUMAR KEWA, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://cis.cgat.gov.in/catlive/pdf/pdf.php?file=TDNVd01TOWpZWFJrYjJNdlkyRjFjMlZzYVhOMEwyMTFiV0poYVM4eU1ESXpMMEYxWjNWemRDOW1OalkxWVRWaVlqa3dabUZsTXpRME1UbG1ZVEk0T1Rjek9XVXpZemN4Tmk1d1pHWT0=

- Arti vs Central Administrative Tribunal (Cat) on 26 April, 2024 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/135799595/

- Calcutta High Court – Appellate side – Case Status : Search by Case Number, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://hcservices.ecourts.gov.in/ecourtindiaHC/cases/case_no.php?state_cd=16&dist_cd=1&court_code=3&stateNm=Calcutta

- service matters doctypes – Delhi High Court – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=service%20matters+doctypes:delhi

- service matters doctypes: bombay – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=service%20matters%20%20%20%20%20doctypes%3A%20bombay&pagenum=6

- service matters doctypes: chennai – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=service%20matters+doctypes:chennai

- Case Query – Bombay High Court, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://bombayhighcourt.nic.in/case_query.php

- About Data Portal – Daksh, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://www.dakshindia.org/about-data-portal/

- Daksh – Judicial data analysis | High Court Data Portal, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://database.dakshindia.org/

- service matters doctypes: judgments – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=service%20matters%20%20%20doctypes%3A%20judgments&pagenum=10

- Article 136 in Constitution of India – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/427855/

- SLP Filing Supreme Court – SSRANA, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://ssrana.in/litigation/special-leave-petition-india/slp-special-leave-petition-filing-supreme-court/

- Reforming Special Leave Petitions: A Two-Tier Approach to Streamline the Supreme Court’s Workload – Constitutional Law Society, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://clsnluo.com/2025/02/24/reforming-special-leave-petitions-a-two-tier-approach-to-streamline-the-supreme-courts-workload/

- Landmark Case Laws on Special Leave Petitions – corpbiz, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://corpbiz.io/learning/landmark-case-laws-on-special-leave-petitions/

- Case Category | Supreme Court of India, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://www.sci.gov.in/case-category/

- Service Matters in the Supreme Court of India & How to win it! – Advocate Jayprakash Somani, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://www.jayprakashsomani.com/blog-detail/service-matter-in-supreme-court-and-how-to-win-it

- Sanjay Kumar Sharma vs Department Of Education on 27 February, 2025 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 31, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/44804493/