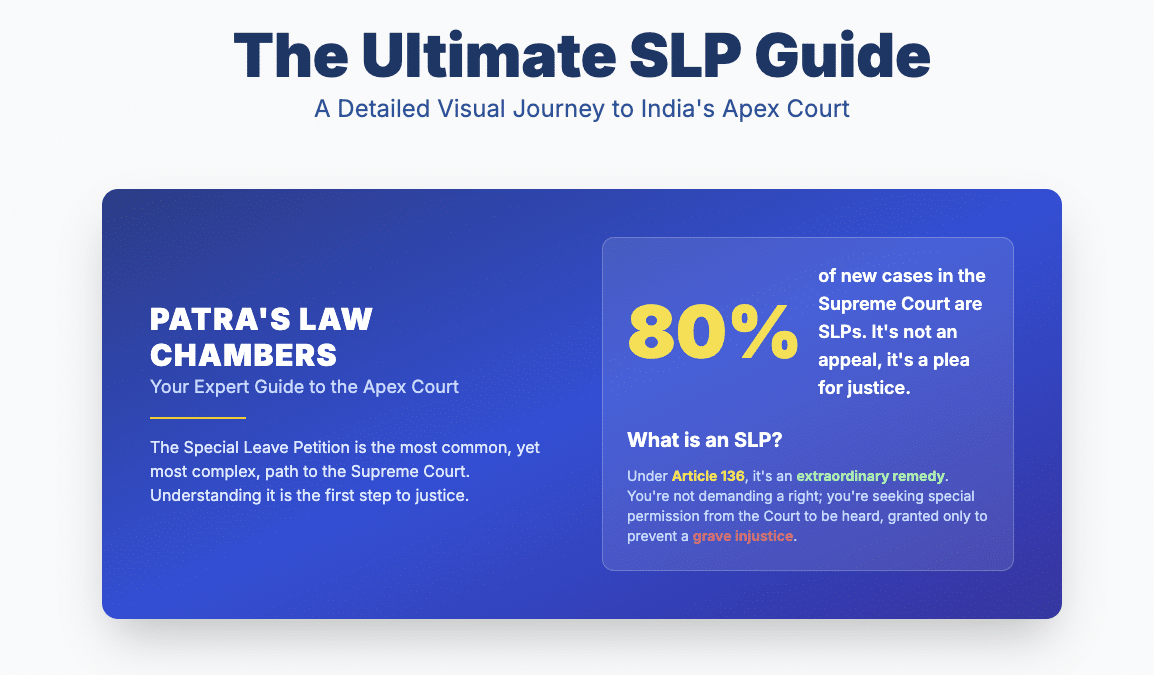

- Special Leave Petition (SLP) is governed by Article 136, granting the Supreme Court extraordinary discretionary power to ensure justice.

- SLPs can address any ruling from any court in India, except military tribunals, covering civil, criminal, and constitutional matters.

- The SLP process allows the Supreme Court to intervene flexibly, often reserved for cases demonstrating gross miscarriage of justice.

- The distinction between SLP and statutory appeals is crucial; SLPs are not a right but a privilege subject to the Court's discretion.

- Petitioners must consult experienced counsel to ensure each SLP meets high thresholds, avoiding frivolous requests that burden the judicial system.

- Filing an SLP involves rigorous procedural compliance, including extensive documentation and adherence to Supreme Court Rules.

- Legal representation by an Advocate-on-Record is mandatory, ensuring the quality and substantive merit of petitions submitted to the Court.

The Ultimate Guide to Filing a Special Leave Petition in the Supreme Court of India: Procedure, Precedents, and Practice

Audio Overview:

Part I: The Constitutional Mandate and Conceptual Framework of the Special Leave Petition

Section 1.1: Genesis and Philosophy of Article 136

The Special Leave Petition (SLP), a unique feature of the Indian judicial system, finds its constitutional basis in Article 136. Its origins, however, predate the Constitution, drawing lineage from the discretionary power once vested in the Privy Council under the Government of India Act, 1935.1 During the Constituent Assembly debates on what was then Draft Article 112, the framers envisioned a powerful tool for the apex court to deliver ultimate justice, unconstrained by the rigid procedural limitations of ordinary appeals.2 Members argued for an explicit expansion of the court’s powers, enabling it to adjudicate cases based on “the principles of jurisprudence and considerations of natural justice”.2

This philosophy shaped Article 136 into what is often described as a “residual power”.3 It was designed to be a constitutional safety valve, a final recourse for litigants when the conventional appellate hierarchy fails to remedy a grave injustice.5 The provision’s extraordinary authority is encapsulated in its opening phrase: “Notwithstanding anything in this Chapter…”.2 This non-obstante clause grants Article 136 an overriding effect over the other appellate provisions contained in Articles 132 to 135, cementing its status as a plenary and exceptional jurisdiction.

However, this power is not entirely without limits. Article 136(2) explicitly excludes from its purview any judgment, determination, sentence, or order passed by a court or tribunal constituted under any law relating to the Armed Forces.2 This clause was added at the behest of the Defence Ministry, which cited similar practices in countries like the UK to maintain the autonomy of military justice systems. The proposal faced strong opposition in the Constituent Assembly from members who argued that it unfairly deprived individuals, including civilians tried by such tribunals, of a right to appeal, particularly in cases involving the death penalty.2 Despite this exclusion, it was clarified that the Supreme Court’s power is not entirely stripped; it retains the authority to intervene if a court-martial exceeds its jurisdiction or if its proceedings are found to be completely arbitrary.2

Section 1.2: The Nature of an SLP: An Extraordinary Discretionary Remedy

An SLP is fundamentally an application seeking “special leave,” which translates to special permission from the Supreme Court to file an appeal.5 It is not an appeal as of right but a privilege that the Court may or may not grant.3 The power vested in the Supreme Court is entirely discretionary, a principle that forms the bedrock of this jurisdiction.1 The Court is under no obligation to hear every petition and can reject an SLP at the threshold, often without assigning any reason, based on its assessment of the case’s merits and national importance.1

The jurisdiction of Article 136 is remarkable for its breadth. It can be invoked against “any judgment, decree, determination, sentence or order in any cause or matter passed or made by any court or tribunal in the territory of India”.2 This wide ambit covers civil, criminal, and constitutional matters, and extends to interlocutory and interim orders, not just final judgments.10 This allows the Supreme Court to intervene at any stage of a proceeding in any judicial or quasi-judicial body to prevent injustice.

Section 1.3: SLP vs. Statutory Appeal: A Critical Distinction

A common source of confusion for litigants is the difference between an SLP and a regular statutory appeal. Understanding this distinction is crucial to appreciating the high threshold for invoking Article 136. While a statutory appeal is a creature of a specific law and provides a litigant with a formal right to challenge a lower court’s decision, an SLP is a constitutional remedy that depends entirely on the discretion of the apex court.

The unfettered, discretionary power of Article 136 was intended to be a “narrow slit” for justice in the most exceptional of cases.1 However, the very breadth and undefined nature of this power have paradoxically led to its prolific use. Litigants, often viewing it as another tier of appeal, file SLPs against “all kinds of orders,” from interim injunctions to final judgments.12 This has created what the Supreme Court itself has described as an “alarming state of affairs”.12 With SLPs constituting approximately 80% of new filings and a backlog of over 33,000 such cases, the Court’s primary function as a constitutional arbiter is under immense strain.14 This overuse threatens to convert the apex court into a “mere Court of Appeal,” diluting its intended purpose of settling the law of the land and addressing matters of profound public and constitutional importance.12 This tension between the provision’s plenary power and its intended purpose is a recurring theme in the jurisprudence surrounding Article 136.

The fundamental differences are summarized below:

| Aspect | Special Leave Petition (SLP) under Article 136 | Statutory Appeal (e.g., under CPC, CrPC) |

| Legal Basis | Article 136 of the Constitution of India.2 | Specific statutes like the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, or the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.8 |

| Nature of Remedy | An extraordinary, discretionary remedy. It is a privilege, not a right.3 | A statutory right, available if prescribed legal conditions are met.8 |

| Governing Authority | The discretion of the Supreme Court alone. | The provisions of the specific statute governing the appeal. |

| Availability | Against “any” judgment or order from “any” court or tribunal in India (except Armed Forces tribunals).2 | Only against specified judgments/orders of specific courts as per the statutory hierarchy.8 |

| Scope of Hearing | The Court first decides whether to grant “leave.” The hearing is on the merits only if leave is granted.3 | The appellate court is generally bound to hear the appeal on its merits if filed correctly.8 |

| Grounds | Not defined. Typically involves a ‘substantial question of law’ or ‘gross miscarriage of justice’.5 | Grounds are typically specified and limited by the governing statute (e.g., error of law, procedural irregularity). |

| Doctrine of Merger | Applies only after leave is granted and the SLP is converted into an appeal.3 A simple dismissal does not cause a merger. | The lower court’s order merges with the appellate court’s order upon the decision of the appeal. |

Part II: Grounds for Invoking the Apex Court’s Jurisdiction

Section 2.1: The Uncodified Spectrum of Grounds=

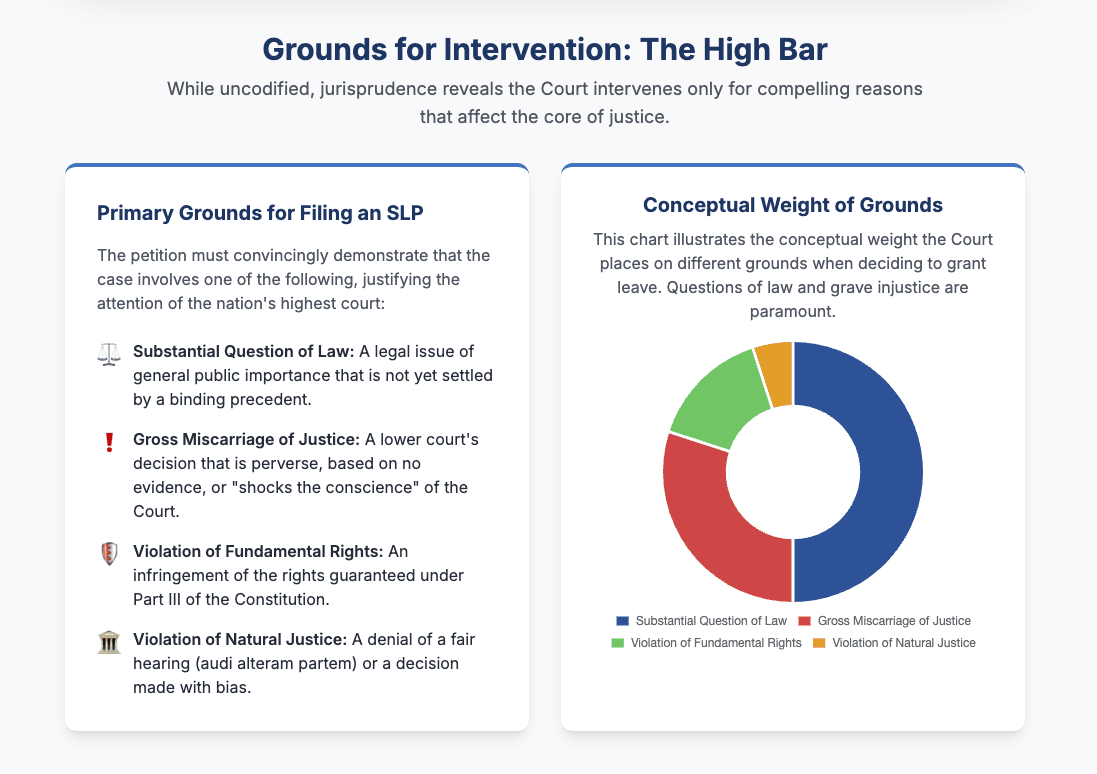

The Constitution deliberately refrains from enumerating specific grounds for filing an SLP, thereby granting the Supreme Court maximum flexibility to do complete justice.5 However, over decades of judicial pronouncements, a clear set of guiding principles has emerged. The Court will generally exercise its discretion only when a case presents features of sufficient gravity. The primary grounds that have been consistently recognized include:

- Violation of Fundamental Rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution.5

- Violation of the principles of natural justice, such as the denial of a fair hearing or a decision rendered by a biased authority.11

- Matters of significant public importance that require an authoritative pronouncement from the apex court.5

- A gross or manifest miscarriage of justice.5

- The existence of a substantial question of law of general importance.5

Section 2.2: Deep Dive: The ‘Substantial Question of Law’ Doctrine

One of the most critical filters for the admission of an SLP is the “substantial question of law” doctrine. This is not just any question of law, but a legal issue of such significance that it can materially affect the outcome of the case and has wider implications for the public.18

The locus classicus on this subject is the Supreme Court’s decision in Sir Chunilal V. Mehta & Sons Ltd. v. Century Spg. & Mfg. Co. Ltd..18 This judgment laid down a multi-pronged test to determine whether a question of law is “substantial.” A question qualifies if it meets one or more of the following criteria:

- General Public Importance: The question affects the public at large, not just the parties to the dispute.18

- Direct and Substantial Impact: It directly and substantially affects the rights of the parties involved.18

- Open Question: The issue is not yet finally settled by a binding precedent of the Supreme Court, the Privy Council, or the Federal Court. There is room for debate or a difference of opinion.18

- Difficulty or Alternative Views: The issue is not free from difficulty and calls for a discussion of alternative interpretations.18

Crucially, the Court has clarified that a question involving the mere application of a well-settled legal principle to a particular set of facts does not rise to the level of a substantial question of law.18 The doctrine is designed to ensure that the Supreme Court’s time is dedicated to settling ambiguous or novel points of law, not to correcting every perceived error in the application of established law.

Section 2.3: Deep Dive: ‘Gross Miscarriage of Justice’ as a Ground for Intervention

The ground of “gross miscarriage of justice” is invoked when the decision of a lower court or tribunal is so fundamentally flawed that it “shocks the conscience” of the Supreme Court.3 This is not about a mere error in judgment but a perversion of the course of justice. An analysis of various Supreme Court judgments reveals that a miscarriage of justice can manifest in several ways 5:

- Manifest Illegality: The lower court’s order contains a clear, undeniable, and grave error of law or procedure that goes to the root of the matter.22

- Perverse Findings: The conclusions reached by the lower court are based on no evidence, are contrary to the evidence on record, or are such that no reasonable judicial mind could have arrived at them. This includes ignoring vital evidence or relying on conjectures and surmises.11

- Violation of Natural Justice: The proceedings were conducted in a manner that was biased, denied a party a fair and reasonable opportunity to be heard, or the deciding authority lacked jurisdiction.22

- Flagrant Disregard for Legal Process: There has been a significant departure from established legal procedures, vitiating the entire trial or proceeding.23

Section 2.4: Interference with Concurrent Findings of Fact

The Supreme Court’s extreme reluctance to interfere with concurrent findings of fact—that is, factual conclusions that have been affirmed by both the trial court and the first appellate court—is a well-established principle. This is not a rigid rule of law, as Article 136 technically grants the Court the power to review any aspect of a case, but rather a self-imposed rule of prudence and judicial discipline.28 This practice reflects the Court’s respect for the judicial hierarchy and acknowledges that the lower courts are best placed to appreciate evidence and assess the credibility of witnesses. The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that it will not act as a “third court of fact”.28

Intervention is therefore reserved for the rarest of exceptional cases.29 The Court will only disturb concurrent findings of fact if it is demonstrated that the findings are perverse, based on a complete misreading or non-consideration of material evidence, or have resulted in a “gross miscarriage of justice”.11 In essence, a factual finding can be so egregiously wrong that it transcends a mere error of fact and becomes a miscarriage of justice, thereby justifying the Court’s intervention under its extraordinary jurisdiction. This is how the Court balances its vast power with the need for judicial comity and finality in litigation.

Part III: The Procedural Labyrinth: A Step-by-Step Guide to Filing an SLP

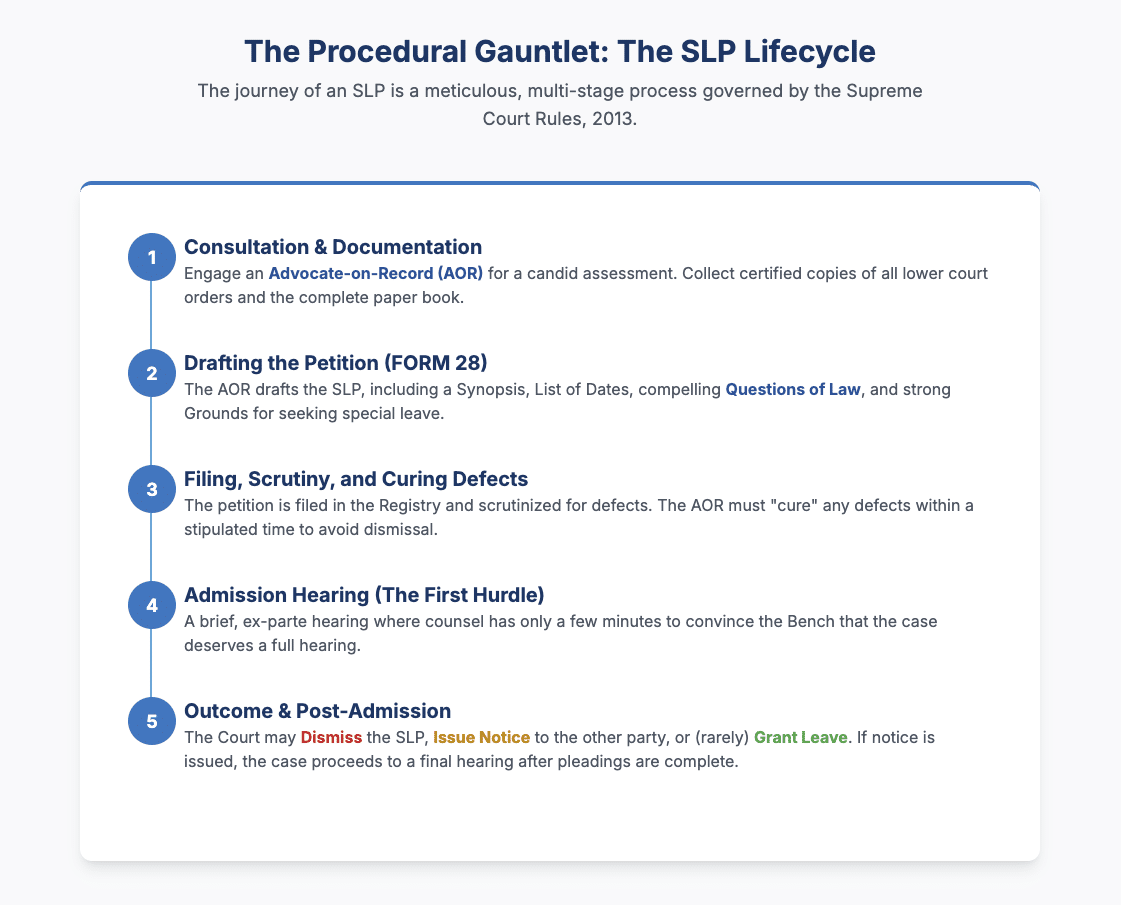

Navigating the procedural requirements for filing an SLP is a meticulous process that demands precision and adherence to the Supreme Court Rules, 2013.

Section 3.1: Pre-Filing Essentials: Case Assessment and Documentation

The journey of an SLP begins long before it reaches the court registry. The first and most critical step is a thorough consultation with an experienced Supreme Court advocate to make a candid assessment of whether the case genuinely meets the high threshold for invoking Article 136.15 Frivolous petitions are strongly discouraged and are likely to be dismissed at the outset.

Once a decision to proceed is made, the next step is the meticulous collection and organization of all necessary documents. A comprehensive checklist includes 30:

- A certified copy of the impugned judgment and/or order of the High Court.

- Certified copies of the judgments and/or orders of all lower courts (e.g., Trial Court, First Appellate Court).

- The complete paper book filed before the High Court, which includes all pleadings, applications, affidavits, and evidence.

- A properly executed Vakalatnama, authorizing the Advocate-on-Record to act on behalf of the petitioner.

- An affidavit from the petitioner verifying the contents of the SLP and the accompanying documents.

- All annexures, which must be certified copies of documents that formed part of the lower court’s record, properly indexed and paginated.16

- An application for condonation of delay with a supporting affidavit, if the petition is filed beyond the prescribed limitation period.

Section 3.2: The Indispensable Role of the Advocate-on-Record (AOR)

The Supreme Court Rules mandate that only an Advocate-on-Record (AOR) can file any petition or document in the Court.30 This requirement is not a mere procedural formality; it is a crucial institutional gatekeeping mechanism. The AOR system is designed to ensure that petitions filed before the apex court are of a certain standard, both in terms of procedural compliance and prima facie merit. The AOR’s signature on a petition is a professional certification to the Court that the matter is fit for its consideration. This places a significant ethical and professional responsibility on the AOR to filter out frivolous or vexatious litigation, thereby acting as the first line of defense in managing the Court’s docket and preserving its judicial time for matters of consequence.

The AOR’s responsibilities are comprehensive, covering the entire lifecycle of the case from drafting and filing to clearing registry defects, receiving all official communications from the court, and ensuring overall compliance with its intricate procedures.17

As the legal experts at Patra’s Law Chambers explain, “The primary duty of an Advocate-on-Record extends beyond mere filing. We must first satisfy ourselves about the prima facie merits of the case and its compliance with the strict standards for invoking Article 136. In doing so, we assist the Court in preserving its extraordinary jurisdiction for the most deserving cases, acting as responsible officers of the Court.

Section 3.3: Drafting the Petition (FORM 28)

The SLP must be drafted in strict accordance with FORM 28 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013.33 The key components of the petition are:

- Synopsis and List of Dates: This section provides a brief, lucid summary of the facts of the case and a chronological list of all relevant dates and events, from the initiation of the dispute to the impugned order. This allows the judges to grasp the essence of the case quickly.11

- Questions of Law: This is arguably the most critical part of the petition. The petitioner must precisely and compellingly frame the substantial questions of law that they want the Supreme Court to consider. These questions form the very basis for the Court’s intervention.34

- Grounds: This section must contain a clear, structured, and legally sound enumeration of the grounds on which special leave is sought. Each ground should directly address the established doctrines, such as the existence of a substantial question of law, a gross miscarriage of justice, or a violation of fundamental rights.7

- Prayer for Relief: The petition must clearly state the relief sought from the Court. This includes the main prayer (e.g., to grant special leave and set aside the impugned order) and any interim prayers (e.g., for a stay on the operation of the impugned order).7

- Declarations: The petition must include mandatory declarations as required by the Rules, such as a statement that no other petition has been filed against the same impugned order.16

Section 3.4: Filing, Scrutiny, and Curing Defects

The drafted petition, along with all required documents, is filed with the Supreme Court Registry. Filing can be done either physically at the counter or through the Court’s e-filing portal.30

Upon filing, the Registry subjects the petition to rigorous scrutiny to ensure it complies with all procedural rules, formatting guidelines, and documentation requirements.30 If any defects are found (e.g., missing documents, incorrect formatting, unclear copies), the Registry notifies the AOR. The AOR is then required to “cure” these defects within a stipulated time. Failure to do so can result in the dismissal of the petition for non-prosecution.30 Once the petition is free from defects, it is assigned a diary number and is listed for an admission hearing before a bench of the Court.30

Section 3.5: The Limitation Period and Condonation of Delay

The Supreme Court Rules prescribe strict timelines for filing an SLP:

- 90 days from the date of the judgment or order of the High Court.1

- 60 days if the SLP is filed against an order of the High Court refusing to grant a certificate of fitness for appeal to the Supreme Court.1

If a petition is filed after this period, it must be accompanied by an application for condonation of delay, supported by an affidavit explaining the reasons for the delay.37 The Court has the discretionary power to condone the delay if the petitioner can demonstrate “sufficient cause” for not filing in time. While the Court often adopts a liberal approach, particularly if the case is meritorious, it will not condone delays that are a result of negligence, inaction, or lack of due diligence.39

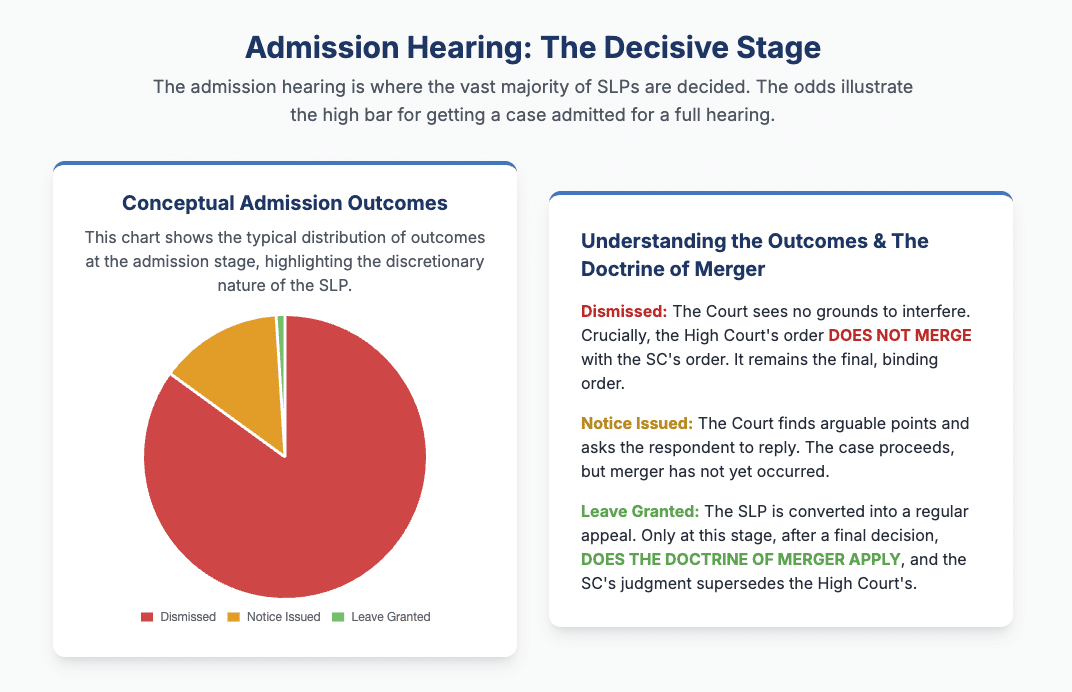

Section 3.6: The Admission Hearing: The First Hurdle

The admission hearing is the first and often the most crucial stage for an SLP. It is typically a brief, ex-parte hearing where the petitioner’s counsel gets a few minutes to present oral arguments and convince the Bench that the case warrants the Court’s attention.10 The entire focus is on demonstrating, prima facie, that the petition raises a substantial question of law or involves a gross miscarriage of justice.

There are three possible outcomes of this hearing:

- Dismissal: If the Bench is not convinced, it will dismiss the SLP. The order may be a simple, non-speaking one (e.g., “The Special Leave Petition is dismissed”) or a speaking order providing brief reasons for the dismissal.

- Issue Notice: If the Bench finds that the petition has merit and raises arguable issues, it will “issue notice” to the respondent(s), directing them to file a response (counter-affidavit) within a specified time.9 The matter is then scheduled for a later date.

- Grant Leave: In very rare instances, if the case is exceptionally clear, the Court may grant leave to appeal at the admission stage itself, thereby converting the SLP into a regular Civil or Criminal Appeal.5

Section 3.7: Post-Admission: The SLP Becomes an Appeal

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Article 136 is uniquely divided into two distinct stages, a legal construct with profound implications for the finality of lower court orders. The first stage is the discretionary “leave” stage, culminating in the admission hearing. The second stage, the “appeal” stage, commences only if and when the Court grants leave.3

This bifurcation is critical to understanding the doctrine of merger. If an SLP is dismissed at the first stage (i.e., leave is refused), the Supreme Court is not exercising its appellate jurisdiction; it is merely declining to grant permission to appeal. Consequently, the High Court’s order does not merge with the Supreme Court’s dismissal order. The High Court’s order remains the final and binding decision, and other remedies, such as a review petition before the High Court, may still be available.3

However, once leave is granted, the SLP is converted into an appeal, and the Supreme Court becomes seized of the matter in its full appellate capacity. The final judgment delivered by the Supreme Court after a full hearing—whether it affirms, modifies, or reverses the High Court’s decision—will supersede the lower court’s order, which merges into the Supreme Court’s final judgment.3 This sophisticated two-stage process allows the Court to efficiently manage its vast docket by summarily disposing of a majority of SLPs without creating a binding precedent on the merits, while reserving the full weight of its appellate authority for the select few cases it chooses to admit.

After notice is issued, the respondent files a counter-affidavit detailing their defense. The petitioner may then file a rejoinder to the counter-affidavit.5 Once the pleadings are complete, the matter is listed for a final, detailed hearing as a regular appeal, where counsel for both sides present their arguments on merits. The Court then delivers its final judgment, which becomes the law of the land.

Part IV: A Compendium of Landmark Jurisprudence (Analysis of 30+ Leading Judgments)

The jurisprudence of Article 136 is a rich tapestry woven from decades of judicial interpretation. The following compendium analyzes over 30 leading judgments that have defined the scope, limitations, and application of this extraordinary power.

Section 4.1: Foundational Principles & Scope of Article 136

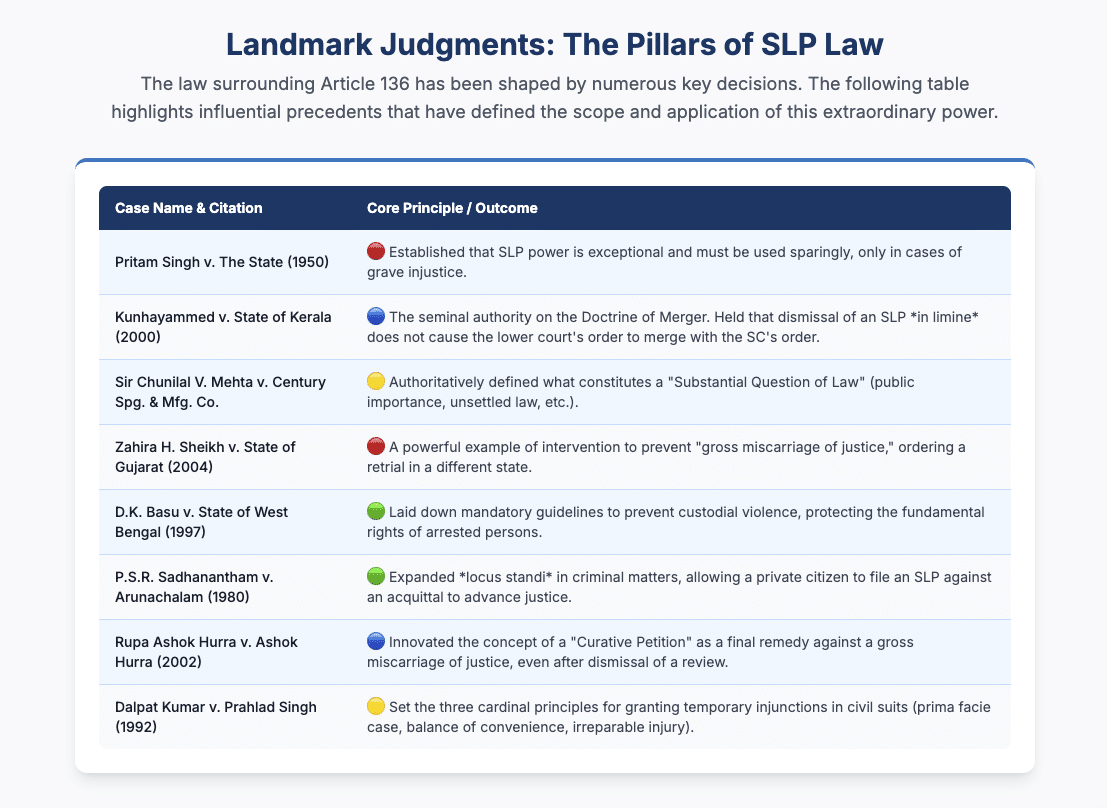

- Pritam Singh v. The State (1950): This foundational judgment established that the Supreme Court is not a regular court of criminal appeal. It laid down the seminal principle that the discretionary power under Article 136 should be exercised only “sparingly and in exceptional cases” where “substantial and grave injustice” has been demonstrated.5

- Dhakeswari Cotton Mills Ltd. v. CIT (1955): The Court held that it would intervene under Article 136 if a tribunal acts in violation of the principles of natural justice, for instance, by relying on evidence that was not disclosed to the aggrieved party, thereby denying them a fair opportunity to rebut it.42

- Mathai @ Joby v. George (2010): Expressing deep concern over the “floodgates” of SLPs converting the Court into a general court of appeal, a Division Bench referred the matter to a Constitution Bench to formulate guidelines on the kinds of cases that should be entertained under Article 136. This case starkly highlights the tension between the Court’s expansive powers and its overwhelming caseload.3

- P. Builders v. A. Ramadas Rao (2011): Reaffirming the principles from Pritam Singh, the Court reiterated that special leave should not be granted unless the petitioner proves the existence of “exceptional and special circumstances” leading to “substantial and grave injustice”.14

- State of Rajasthan v. Sohan Lal & Ors. (2004): This case clarified that Article 136 does not confer an automatic right of appeal on any party. It also established that a summary dismissal of an SLP in limine (at the threshold) does not constitute a binding precedent under Article 141 of the Constitution.47

Section 4.2: The Doctrine of Merger and Procedural Nuances

- Kunhayammed v. State of Kerala (2000): This is the seminal authority on the doctrine of merger in the context of SLPs. The Court meticulously explained the two-stage process of Article 136 jurisdiction. It held that if an SLP is dismissed at the threshold (Stage 1), there is no merger of the lower court’s order. The doctrine of merger applies only when leave is granted and the SLP is converted into an appeal (Stage 2), which is then decided on merits.3

- Khoday Distilleries Ltd. v. Sri Mahadeshwara Sahakara Sakkare Karkhane Ltd. (2019): A larger bench of the Supreme Court affirmed and settled the legal position laid down in Kunhayammed, providing finality to the principles regarding the non-application of the doctrine of merger upon the summary dismissal of an SLP.51

- Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra (2002): In a path-breaking decision, the Supreme Court innovated the concept of a “curative petition.” It held that even after the dismissal of a review petition, the Court could entertain a curative petition to prevent abuse of its process and to cure a gross miscarriage of justice, providing a final, albeit extremely narrow, window for relief.9

Section 4.3: SLPs in Criminal Matters: Acquittals, Convictions, and Fair Trial

- Sanwat Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1961): The Court laid down the principles governing an appeal against acquittal. It held that while an appellate court has full power to review evidence and reverse an acquittal, it must give proper weight and consideration to the trial court’s findings and the double presumption of innocence in favour of the accused.27

- Rajesh Prasad v. State of Bihar (2022): Reaffirming earlier precedents, the Court held that its intervention in an order of acquittal is warranted only in exceptional circumstances, such as when the High Court’s reasoning is found to be perverse, based on surmises and conjectures, or would result in a significant miscarriage of justice.54

- Zahira Habibulla H. Sheikh v. State of Gujarat (2004) (Best Bakery Case): This case is a powerful illustration of the Court’s extraordinary powers. Faced with a complete failure of the justice delivery system due to witness intimidation and a flawed investigation during the Gujarat riots, the Court, to prevent a “gross miscarriage of justice,” ordered a retrial of the case outside the state of Gujarat.57

- K. Basu v. State of West Bengal (1997): Although a writ petition, this landmark judgment laid down mandatory procedural requirements for arrest and detention to prevent custodial violence. These guidelines are frequently invoked in SLPs where the petitioner alleges violations of fundamental rights during criminal proceedings.58

- Joginder Kumar v. State of U.P. (1994): The Court laid down crucial guidelines for arrest, emphasizing that the power to arrest must be exercised with justification and not arbitrarily. It established that an arrest cannot be made in a routine manner on a mere allegation, a principle that forms the basis for many SLPs challenging illegal detention.60

- Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab (1994): While upholding the constitutional validity of the stringent Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), the Court used its powers to read down certain provisions and issue strict guidelines to prevent their misuse. This case demonstrates the Court’s role in balancing national security concerns with individual liberties.5

- State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal (1992): This judgment provided an illustrative, though not exhaustive, list of categories where the High Court could exercise its inherent powers under Section 482 CrPC to quash an FIR. These grounds are frequently cited in SLPs filed against High Court orders refusing to quash criminal proceedings.64

Section 4.4: Locus Standi and Public Interest

- S.R. Sadhanantham v. Arunachalam (1980): The Court significantly expanded the concept of locus standi in criminal matters, holding that a private citizen (in this case, the brother of the deceased) had the right to file an SLP against an order of acquittal. It reasoned that the Court’s power under Article 136 is meant to advance the cause of justice, regardless of who invokes it.42

- Sheonandan Paswan v. State of Bihar (1987): The Court affirmed that any member of the public has the locus standi to oppose an application for the withdrawal of prosecution, especially in cases of corruption which are offences against society. This reinforces the public’s stake in the integrity of the criminal justice system.69

- Bihar Legal Support Society v. Chief Justice of India (1986): In this case, the Court emphatically stated that the special leave petitions of “small men” are as much entitled to consideration as those of “big industrialists.” It underscored the Court’s constitutional duty to ensure access to justice for the poor and disadvantaged sections of society.70

- Common Cause, A Registered Society v. Union of India (1996): This case is a leading example of a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) where the Court entertained a petition on a matter of immense public importance (in this instance, related to passive euthanasia and living wills). It demonstrates the wide scope of issues that can be brought before the Court, which often involve SLPs in related or subsequent proceedings.72

Section 4.5: Constitutional and Administrative Law Interface

- R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak (1988): A seven-judge bench took the extraordinary step of recalling an earlier direction of the Court that had transferred a corruption case to the High Court, holding that the order violated the accused’s fundamental rights. This judgment established the principle that the Supreme Court has the inherent power to correct its own errors to prevent a miscarriage of justice.5

- Union Carbide Corporation v. Union of India (1991): In the aftermath of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, the Supreme Court exercised its plenary powers to review and ultimately uphold the controversial settlement, showcasing the application of Article 136 in matters of unparalleled national and humanitarian significance.51

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973): This monumental judgment established the “basic structure doctrine,” which holds that while Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, it cannot alter its basic features. Though not an SLP case itself, this doctrine defines the ultimate constitutional limits that are often the subject matter of SLPs challenging constitutional amendments.77

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978): This case revolutionized the interpretation of Article 21 by holding that the “procedure established by law” must be fair, just, and reasonable. This principle has become a cornerstone for countless SLPs challenging arbitrary state action.51

- Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner (1978): The Court interpreted the vast “reservoir of power” of the Election Commission under Article 324 to ensure free and fair elections. This principle is frequently tested and applied in SLPs arising from complex electoral disputes.51

Section 4.6: SLPs in Civil, Labour, and Service Matters

- Jaswant Sugar Mills Ltd. v. Lakshmichand (1963): The Court clarified that not every authority that determines rights is a “tribunal” for the purposes of Article 136. It held that a Conciliation Officer under the Industrial Disputes Act, performing administrative functions, was not a tribunal, thus limiting the scope of SLPs against non-judicial bodies.27

- Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works Ltd. v. Their Workmen (1959): The Court exercised its SLP jurisdiction to adjudicate on issues of dearness allowance and the government’s power to transfer industrial disputes, demonstrating its crucial role in settling principles of labour law.14

- Gujarat Steel Tubes Ltd. v. Gujarat Steel Tubes Mazdoor Sabha (1980): In a case involving the mass termination of employees following an illegal strike, the Court intervened to modify an arbitrator’s award and direct reinstatement, emphasizing its role in ensuring social justice and protecting workmen from disproportionate punishment.84

- Hindustan Tin Works Pvt. Ltd. v. The Employees (1979): Where retrenchment was found to be unjustified, the Court, while hearing the SLP, limited the issue to the quantum of back wages and awarded 75%, thereby establishing equitable principles for granting relief in cases of illegal termination.86

- Sadhu Ram v. Delhi Transport Corporation (1983): The Court held that the High Court, exercising its writ jurisdiction under Article 226, should not act as an appellate court over a Labour Court’s findings of fact. This principle of limited judicial review is a common issue in SLPs arising from writ petitions in service matters.88

- Chairman, Railway Board v. Chandrimas Das (2000): The Court expanded the scope of public law remedy for the violation of fundamental rights, holding the State vicariously liable for the gang-rape of a foreign national by railway employees in a railway building. It affirmed that fundamental rights are available to all persons, citizen or not, on Indian soil.89

- Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singh (1992): This judgment authoritatively laid down the three cardinal principles for the grant of a temporary injunction: (i) a prima facie case, (ii) the balance of convenience in favour of the applicant, and (iii) the likelihood of irreparable injury if the injunction is refused. These principles are frequently the subject matter of SLPs arising from interlocutory orders of High Courts.90

Part V: Practical Considerations and Strategic Insights

Section 5.1: Crafting a Compelling Petition: The Art of Persuasion

Drafting an SLP is not merely a legal exercise; it is an art of persuasion. Given that judges have only a few minutes to decide whether to entertain a petition, its structure and content are paramount. Best practices include:

- Focus on the “Why”: The synopsis and grounds must immediately answer why the case is “special” and requires the Supreme Court’s intervention. Instead of merely rehashing facts, the narrative should be built around the grave injustice or the novel question of law.

- Clarity and Precision in Questions of Law: The questions of law should be framed concisely, powerfully, and in a manner that immediately highlights their significance.

- Brevity is Key: Acknowledge the Court’s immense workload. A petition that is direct, to the point, and free of jargon is more likely to be effective.

As the experts at Patra’s Law Chambers advise, “A successful SLP is one that demonstrates, from the very first page, a manifest injustice or a legal question of such national importance that the apex court cannot afford to ignore it. The first impression is often the only impression you get.”

Section 5.2: The Financial Aspect: Court Fees and Legal Costs

Engaging in litigation at the Supreme Court involves significant financial commitment. A realistic assessment of costs is essential for any potential petitioner.

- Court Fees: The official court fees for filing an SLP are relatively modest. As per the Supreme Court Rules, the fee is INR 1,500 for a standard SLP. For certain special cases, this fee can be INR 5,000. Additionally, a fee of INR 200 is charged for each accompanying application, such as one for stay or condonation of delay.5

- Other Costs: The more substantial costs are professional fees. These include the fees for the Advocate-on-Record, who manages the entire filing process, and potentially the fees for a Senior Advocate, who is engaged for their expertise in oral arguments during the admission hearing and final hearing. Other miscellaneous expenses include costs for printing, notarization, and administrative tasks.

Section 5.3: Concluding Remarks: The SLP as a Guardian of Justice

The Special Leave Petition under Article 136 stands as a testament to the constitutional vision of ensuring that justice is accessible at the highest level, transcending procedural barriers. It is a vital instrument for correcting grave errors of law and preventing miscarriages of justice, acting as the ultimate guardian of the rule of law. However, this extraordinary jurisdiction is under considerable strain due to an ever-increasing caseload, which threatens to dilute its exceptional character.

A profound responsibility, therefore, rests upon both the Bench and the Bar. The judiciary must continue to exercise its discretion with utmost caution and self-restraint, preserving this power for cases that truly warrant its intervention. The legal fraternity, particularly Advocates-on-Record, must act as diligent gatekeepers, discouraging frivolous petitions and ensuring that only matters of substance are brought before the Court.

As a final thought from Patra’s Law Chambers, “Navigating the extraordinary jurisdiction of the Supreme Court requires not just legal knowledge but strategic foresight and specialized expertise. The powerful remedy of an SLP must be invoked responsibly and effectively, ensuring that this ‘sentinel on the qui vive’ continues to stand guard over the constitutional promise of justice for all.”

Resources:SLP Guide and Legal Services_

Works cited

- Article 136 of the Indian Constitution – CivilsDaily, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.civilsdaily.com/news/article-136-of-the-indian-constitution/

- Article 136: Special leave to appeal by the Supreme Court – Constitution of India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.constitutionofindia.net/articles/article-136-special-leave-to-appeal-by-the-supreme-court/

- Special Leave Petition in Indian Judicial System – Law Senate, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.lawsenate.com/publications/articles/special-leave-petition-slp.pdf

- Residual Power of Supreme Court – E-Magazine….::, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/orissareview/2016/May-June/engpdf/100-103.pdf

- Special Leave Petition: Meaning, Features, Process and Who can file it ? – Century Law Firm, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.centurylawfirm.in/blog/special-leave-petition-slp-meaning-features-process-and-who-can-file-it/

- org, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/427855/#:~:text=Special%20leave%20to%20appeal%20by,in%20the%20territory%20of%20India.

- What is a Special Leave Petition and how to draft one – Knowledge Base – A LawSikho Initiative -, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://knowledgebase.lawsikho.com/special-leave-petition/

- Difference Between Special Leave Petition (SLP) and Appeal, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.jayprakashsomani.com/blog-detail/difference-between-slp-and-appeal

- Extraordinary jurisdiction of the Supreme court under Article 136 – Xperts Legal Updates, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://xpertslegal.com/blog/extraordinary-jurisdiction-of-the-supreme-court-under-article-136/

- Special Leave Petition (SLP): Key Features, Process, and Landmark Cases – Rest The Case, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/special-leave-petition

- Special Leave Petition – Drishti Judiciary, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/ttp-constitution-of-india/special-leave-petition

- Article 136 only a discretionary remedy, says Supreme Court – The Hindu, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/Article-136-only-a-discretionary-remedy-says-Supreme-Court/article16578415.ece

- What Makes Special Leave Petitions ‘Special’? – Daksh, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.dakshindia.org/what-makes-special-leave-petitions-special/

- Reforming Special Leave Petitions: A Two-Tier Approach to Streamline the Supreme Court’s Workload – Constitutional Law Society, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://clsnluo.com/2025/02/24/reforming-special-leave-petitions-a-two-tier-approach-to-streamline-the-supreme-courts-workload/

- How to file a civil appeal, Special Leave Petition (SLP) in Supreme Court of India?, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://shashikiranadvocate.com/how-to-file-a-civil-appeal-special-leave-petition-slp-in-supreme-court-of-india/

- Special Leave Petition (SLP) – Aegis Legal LLP, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.aegislegalllp.com/supreme-court-practice/special-leave-petition.html

- Mastering the Legal Maze: A Comprehensive Guide to Special Leave Petitions before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India – Vedic, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://vediclegal.in/special-leave-petitions-in-supreme-court-of-india/

- meaning of substantial question of law – Supreme Today AI, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://supremetoday.ai/issue/meaning-of-substantial-question-of-law

- Judicial Interpretation of Substantial Question of Law | LawTeacher.net, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.lawteacher.net/free-law-essays/administrative-law/judicial-interpretation-of-substantial-questionable-law-administrative-law-essay.php

- Sir Chunilal v. Mehta and Sons, Ltd vs the Century Spinning and Manufacturing … on 5 March, 1962 – Scribd, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/856724093/Sir-Chunilal-v-Mehta-and-Sons-Ltd-vs-the-Century-Spinning-and-Manufacturing-on-5-March-1962

- ai, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://supremetoday.ai/issue/supreme-court-on-substantial-question-of-law-affecting-public-interest-in-SLP#:~:text=The%20Court%20has%20established%20criteria,unsettled%20by%20the%20highest%20courts.

- gross+miscarriage+of+justice | Indian Case Law | Law | CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/gross%2Bmiscarriage%2Bof%2Bjustice

- gross miscarriage of justice – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=gross%20miscarriage%20of%20justice

- Cases of appeals to Supreme Court | Capital Punishment | Law Commission of India Reports – AdvocateKhoj, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/lawreports/capitalpunishment/154.php?Title=Capital%20Punishment&STitle=Cases%20of%20appeals%20to%20Supreme%20Court

- miscarriage of justice – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=miscarriage%20of%20justice

- Haripada Dey vs The State Of West Bengaland Another on 5 September, 1956, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1665883/?type=print

- Special Leave Petition – What, How & When – iPleaders, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/special-leave-petition/

- SLP | PDF | Supreme Court Of India | Jurisdiction – Scribd, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/451488898/slp

- concurrent findings doctypes: supremecourt – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=concurrent%20findings%20%20%20doctypes%3A%20supremecourt&pagenum=2

- SLP Filing in Supreme Court | Article 136 Guide and Procedure, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.duasnduas.com/resources/slp-filing-process-supreme-court-india/

- Filing a Special Leave Petition in Supreme Court (Civil), accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.jayprakashsomani.com/blog-detail/slp-civil-in-supreme-court

- Check List – ::Telangana State Legal Services Authority::, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://tslsa.telangana.gov.in/checklist.pdf

- SLP Filing Supreme Court – SSRANA, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://ssrana.in/litigation/special-leave-petition-india/slp-special-leave-petition-filing-supreme-court/

- F O R M – 28 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA (Order XVI Rule …, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec0490f1f4972d133619a60c30f3559e/uploads/2024/01/2024011779.pdf

- in, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://ssrana.in/ufaqs/special-leave-petition-slp-india/

- dated 4/ 9/ 97 F.No. 494\ 1\ 97- CUS. VI Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Revenue – India Code, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://upload.indiacode.nic.in/showfile?actid=AC_CEN_2_2_00042_196252_1534829466423&type=circular&filename=Cir33-97.pdf

- Delay condoned. These Special Leave Petitions are dismissed following the order dated 26.07.2024 passed by this Court in SLP (C), accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.sci.gov.in/sci-get-pdf/?diary_no=490142024&type=o&order_date=2025-01-20&from=latest_judgements_order

- APPLICATION FOR CONDONATION OF DELAY IN FILING THE SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION – Legal Light Consulting – Leading Law Firm in India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://legallightconsulting.com/application-for-condonation-of-delay-in-filing-the-special-leave-petition/

- condonation of delay in filing special leave petition – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=condonation%20of%20delay%20in%20filing%20special%20leave%20petition

- J U D G M E N T – Supreme Court of India, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2017/14596/14596_2017_15_1502_52056_Judgement_08-Apr-2024.pdf

- 29CSR3 – West Virginia Board of Examiners for Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.wvspeechandaudiology.com/Portals/WVSpeechAndAudiology/WEBSITE/29-3%20Contested%20Case%20Hearing%20Procedures_1.pdf?ver=R4v03m_8LJGo9O4cGKKfKA%3D%3D

- SPECIAL LEAVE PETITIONS, AN IMPEDIMENT TO JUSTICE: NEED FOR STRUCTURAL CHANGES TO ENSURE EFFICIENT TIME ALLOCATION OF THE COURT – Manupatra, accessed on July 29, 2025, http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/23DCCFF6-CEA5-4494-9877-40F3C2ABD219.pdf

- Setting the Standard: Special Leave to Appeal under Article 136 of the Indian Constitution, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/setting-the-standard:-special-leave-to-appeal-under-article-136-of-the-indian-constitution/view

- Ensuring Natural Justice in Tax Assessments: Dhakeswari Cotton Mills Ltd. v. Commissioner Of Income Tax, West Bengal – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/ensuring-natural-justice-in-tax-assessments:-dhakeswari-cotton-mills-ltd.-v.-commissioner-of-income-tax,-west-bengal/view

- Clerks and Depot Cashiers of Calcutta Tramways Co. Ltd. v. Calcutta Tramways Co. Ltd.: Supreme Court Upholds Differential Dearness Allowance Rates – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/clerks-and-depot-cashiers-of-calcutta-tramways-co.-ltd.-v.-calcutta-tramways-co.-ltd.:-supreme-court-upholds-differential-dearness-allowance-rates/view

- Clarifying ‘Readiness and Willingness’ and Marshalling Rights in Specific Performance: A Ramadas Rao vs. J.P Builders Judgment Analysis – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/clarifying-%E2%80%98readiness-and-willingness%E2%80%99-and-marshalling-rights-in-specific-performance:-a-ramadas-rao-vs.-j.p-builders-judgment-analysis/view

- article+136+of+constitution+of+india | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/article%2B136%2Bof%2Bconstitution%2Bof%2Bindia

- JUDGMENT/ORDER IN – CRIMINAL APPEAL No. 847 of 2011 at Lucknow Dated-4.5.2017 CASE TITLE – State Of U.P. Vs. Ramshanker & Ors. – eLegalix – Allahabad High Court, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://elegalix.allahabadhighcourt.in/elegalix/WebShowJudgment.do?judgmentID=5474949

- special leave petition under article 136 doctypes: supremecourt – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=special%20leave%20petition%20under%20article%20136+doctypes:supremecourt

- Kunhayammed vs. State of Kerala (2000) 6 SCC 359 | PDF | Judgment (Law) – Scribd, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/627990582/202600006072022-3

- Discretionary Power of The Supreme Court Under Article 136 – Whether Immune From Passing Speaking Orders? – Taxmann, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.taxmann.com/research/income-tax/top-story/105010000000018598/discretionary-power-of-the-supreme-court-under-article-136-%E2%80%93-whether-immune-from-passing-speaking-orders

- IBC Moratorium Does Not Cover Regulatory Penalties – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/supreme-court-observer-law-reports-scolr/ibc-moratorium-does-not-cover-regulatory-penalties-saranga-anilkumar-aggarwal-v-bhavesh-dhirajlal-sheth/

- Curative Petition – Aegis Legal LLP, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.aegislegalllp.com/supreme-court-practice/curative-petition.html

- Appellate Scrutiny in Acquittals: Rajesh Prasad v. State Of Bihar – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/appellate-scrutiny-in-acquittals:-rajesh-prasad-v.-state-of-bihar/view

- Sanwat Singh And Others v. State Of Rajasthan: Defining Appellate Review in Acquittal Cases – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/sanwat-singh-and-others-v.-state-of-rajasthan:-defining-appellate-review-in-acquittal-cases/view

- Article 136 of the COI – Drishti Judiciary, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/current-affairs/article-136-of-the-coi

- Zahira Habibulla H. Shiekh v. State of Gujarat (2004): The Best Bakery case, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.alec.co.in/judgement-page/zahira-habibulla-h-shiekh-v-state-of-gujarat-2004-the-best-bakery-case

- An Analysis of D.K Basu v. State of West Bengal – Jus Scriptum Law, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.jusscriptumlaw.com/post/the-beacon-to-protect-the-rights-and-dignity-of-individuals-an-analysis-of-d-k-basu-v-state-of-wes

- org, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/235756/#:~:text=Basu%20Versus%20State%20of%20West,measure%20to%20prevent%20custodial%20violence.

- docx, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.iilsindia.com/study-material/619970_1598115888.docx

- Joginder Kumar vs State of UP – Case Analysis – Testbook, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/joginder-kumar-vs-state-of-up

- Kartar Singh vs State of Punjab 1994: TADA Act & Constitutional Validity, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/kartar-singh-vs-state-of-punjab

- Law Commission of India Reports | Law Library | AdvocateKhoj, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/lawreports/witnessidentityprotection/31b.php?Title=&STitle=Kartar%20Singh’s%20case:%20(section%2016%20of%20TADA)(1994)

- State of Haryana V. Bhajan Lal (1992 Supp (1) Scc 335) – Dhyeya Law, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.dhyeyalaw.in/state-of-haryana-v-bhajan-lal-1992-supp-1-scc-335

- S.R Sadhanantham v. Arunachalam And Another | Supreme Court Of India | Judgment | Law | CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5609abe6e4b014971140d921

- Arunachalam v. P. S.R Sadhanantham And Another | Supreme Court Of India – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5609abdee4b014971140d798

- Private Citizen’s Right to Appeal Acquittal under Article 136: An Analysis of P.S.R Sadhanantham v. Arunachalam: Supreme Court Of India | CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/private-citizen’s-right-to-appeal-acquittal-under-article-136:-an-analysis-of-p.s.r-sadhanantham-v.-arunachalam/view

- 142 of 2017 Applicant :- Smt. Shireen Opposite Party :- State Of U.P – eLegalix, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://elegalix.allahabadhighcourt.in/elegalix/WebDownloadOriginalHCJudgmentDocument.do?translatedJudgmentID=5202

- WITHDRAWAL FROM PROSECUTION, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s37a68443f5c80d181c42967cd71612af1/uploads/2025/03/202503191390332686.pdf

- Bihar Legal Support Society vs The Chief Justice Of India & Anr on 19 November, 1986 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1041403/

- AN ANALYSIS: LEGAL AID IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM – Indian Journal of Integrated Research in Law, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://ijirl.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/AN-ANALYSIS-LEGAL-AID-IN-THE-CRIMINAL-JUSTICE-SYSTEM.pdf

- Common Cause (A Regd. Society) vs. Union of India and Anr. – Privacy Law Library, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://privacylibrary.ccgnlud.org/case/common-cause-a-regd-society-vs-union-of-india-uoi-and-ors

- Common Cause v. Union of India | Naya Legal, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.nayalegal.com/common-cause-v-union-of-india

- AR Antulay vs RS Nayak Case Analysis – Testbook, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/ar-antulay-vs-rs-nayak

- R. Antulay vs. R.S. Nayak & Anr. (1988) : case analysis – iPleaders, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/a-r-antulay-v-r-s-nayak-anr-a-legal-analysis/

- UNION CARBIDE CORPORATION VS UNION OF INDIA ETC – Prajwal Verma & Suhani Gupta – ijalr, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://ijalr.in/volume-3/issue-2/union-carbide-corporation-vs-union-of-india-etc-prajwal-verma-suhani-gupta/

- Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) : case analysis – iPleaders, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/kbharatikerala/

- Maneka Gandhi vs Union of India – Launchpad IAS, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://launchpadeducation.in/maneka-gandhi-vs-union-of-india/

- election commission of india, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://hindi.eci.gov.in/files/file/11002-eci-order-dated-1642021-on-campaign-rallies-public-meeting-etc/?do=download&r=26327&confirm=1&t=1&csrfKey=9d7670c9a41c0c3e9004ca12958628f9

- Supreme Court of India Establishes Limits on Appeals Against Conciliation Officer’s Directions in Industrial Disputes – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/supreme-court-of-india-establishes-limits-on-appeals-against-conciliation-officer’s-directions-in-industrial-disputes/view

- State of Uttar Pradesh Vs. M/s. Jaswant Sugar Mills Ltd. | Latest Supreme Court of India Judgments | Law Library | AdvocateKhoj, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/judgments/announcement.php?WID=4895

- Government’s Authority to Transfer Industrial Disputes Between Tribunals: Insights from Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works Ltd. v Their Workmen (1959) – CaseMine, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/government’s-authority-to-transfer-industrial-disputes-between-tribunals:-insights-from-bengal-chemical-&-pharmaceutical-works-ltd.-v-their-workmen-(1959)/view

- Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works … vs Its Workmen on 16 September, 1968 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1167165/

- Gujarat Steel Tubes Ltd vs Gujarat Steel Tubes Mazdoor Sabha on 19 November, 1979 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/609478/

- Gujarat Steel Tubes Ltd. Vs. Gujarat Steel Tubes Mazdoor Sabha [1979] INSC 242 (19 November 1979) 1979 Latest Caselaw 242 SC – Latest Laws, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.latestlaws.com/latest-caselaw/1979/november/1979-latest-caselaw-242-sc/

- Hindustan Tin Works Pvt. Ltd vs Empkoyees Of Hindustan Tin Works Pvt. … on 7 September, 1978, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/465896/

- Supreme Court (SC) Judgements on Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 – Latest Laws, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.latestlaws.com/related-judgements/525/sc-judgement-on-industrial-disputes-act-1947/

- Sadhu Ram vs Delhi Transport Corporation on 25 August, 1983 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/525337/

- The Chairman, Railway Board & ORS v. Mrs. Chandrima Das & ORS | Gender Justice – Law.Cornell.Edu, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/gender-justice/resource/the_chairman_railway_board_ors_v_mrs_chandrima_das_ors

- Dalpat kumar versus pralad singh 1992 judgement – Supreme Today AI, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://supremetoday.ai/issue/Dalpat-kumar-versus-pralad-singh-1992-judgement

- Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singh | PDF | Lawsuit | Injunction – Scribd, accessed on July 29, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/507094820/Dalpat-Kumar-v-Prahlad-Singh