- Appointment creates legal status, not an absolute right to the post; right is to fair, non-arbitrary consideration under Article 16.

- Appointments require an existing sanctioned vacancy; government discretion to fill vacancies is reviewable only for arbitrariness or mala fides.

- Appointing Authority must be competent; appointments by an incompetent authority are void ab initio and cannot be cured.

- Government service originates as contract but converts to public status, enabling unilateral rule changes and constitutional protections (Articles 309–311).

- Pleasure doctrine (Article 310) governs tenure but is limited by Article 311 safeguards and Tulsiram Patel jurisprudence.

- Appointment types (permanent, temporary, officiating, ad hoc, daily wagers) determine rights, lien, and protection against termination.

- Illegal appointments (statutory violation, fraud) are void; irregular ones may be regularized; natural justice applies depending on defect.

The Law of Appointment in Govt. Service Explained

Introduction

The act of ‘appointment’ is the foundational event in public service, establishing the legal relationship between the state and the individual. It is the moment a candidate transitions from an applicant to a public servant, acquiring a distinct legal status governed by constitutional principles and statutory rules. This study guide provides a comprehensive legal analysis of the principles governing this crucial relationship. We will examine the sources from which appointments are made, the nature of an individual’s rights, the authority empowered to make appointments, the tenure of office under the ‘pleasure doctrine’, and the grounds upon which an appointment may be cancelled. A thorough understanding of these principles is not merely academic; it is critical for navigating examinations in administrative and service law and for appreciating the framework that ensures fairness, order, and accountability in public employment.

——————————————————————————–

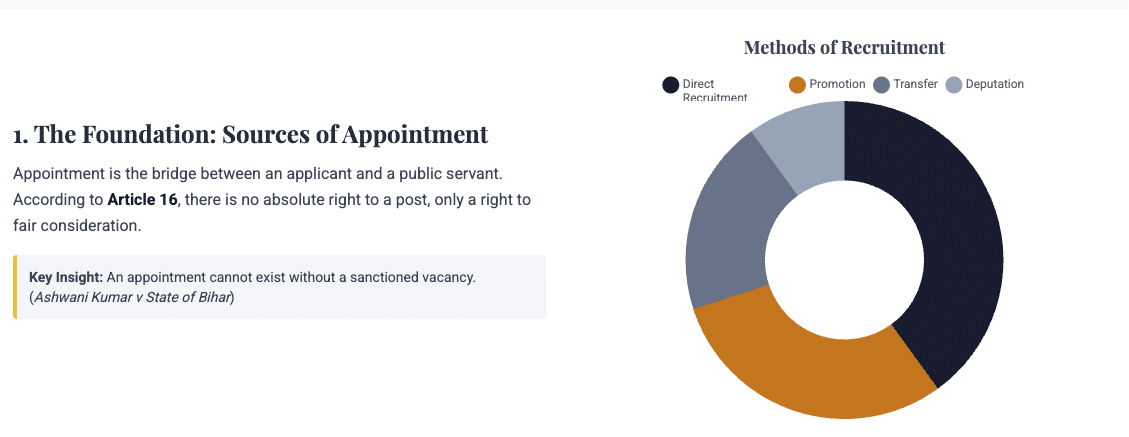

1. The Foundation: Source and Right of Appointment

1.1. Strategic Overview

Understanding the methods of appointment and the precise legal nature of a candidate’s ‘right’ to a public post is the starting point for all service law jurisprudence. This section addresses a frequently litigated tension: the conflict between an individual’s expectation of fair play and the state’s executive discretion in public employment. It deconstructs the common misconception of an absolute right to a government job, replacing it with the constitutionally grounded principle that the fundamental right is not to the post itself, but to fair and non-arbitrary consideration for it under Article 16 of the Constitution.

1.2. Analysis of Core Principles

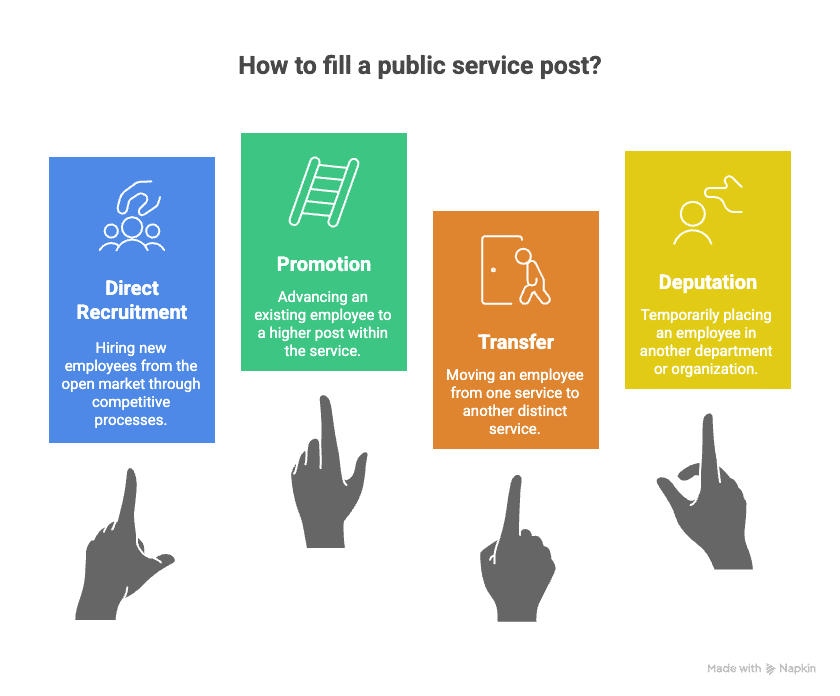

- Sources of Appointment: An appointment to public service can be made through one of four primary methods:

- Direct Recruitment: The process of hiring new employees from the open market, typically through competitive examinations and interviews.

- Promotion: The advancement of an existing employee to a higher post or grade within the service.

- Transfer: The movement of an employee from one service to another distinct service.

- Deputation: The temporary placement of an employee from their parent department to another department or organization for a specified period.

- The Right to Appointment: The fundamental legal principle, anchored in Article 16 of the Constitution, is that a candidate possesses no absolute legal right to be appointed to a public post. The right is limited to fair consideration for the post in accordance with the existing rules. A successful candidate who has cleared all examinations and interviews acquires a ‘reasonable expectation’ of being appointed if a vacancy exists. However, this does not mature into a vested legal right. The state is not obligated to fill every available vacancy, but if it chooses not to, it must provide justifiable and non-arbitrary reasons for its decision. A key exception, compassionate appointment, is not a right but a concession that can be modified or even wound up by the employer depending on its policies, financial capacity, and the availability of posts.

- The Necessity of a Vacancy: It is an axiomatic principle of service law that an appointment can only be made against an existing, sanctioned vacancy. There cannot be an employee without a post. The government retains significant policy discretion in deciding whether, and how many, vacancies to fill. This discretion is not absolute and is subject to judicial review, but the grounds for interference are narrow. A court will typically intervene only if the decision not to fill vacancies is proven to be arbitrary, tainted by mala fides, or inconsistent with the principles of equality under Article 14 of the Constitution.

1.3. Landmark Case Law

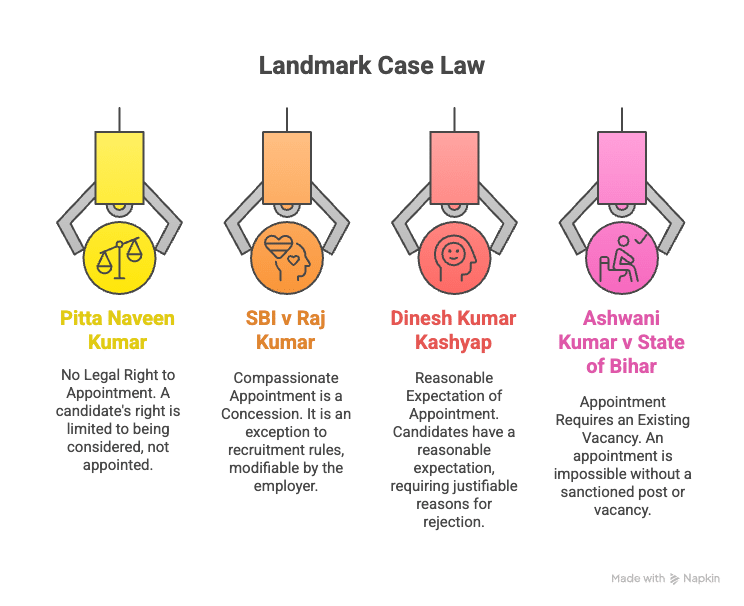

- Pitta Naveen Kumar v Raja Narasaiah Sangiti, (2006) 10 SCC 261: No Legal Right to Appointment. This case firmly establishes that a candidate’s right under Article 16 is limited to being considered for appointment; it is not an absolute right to the appointment itself.

- SBI v Raj Kumar, (2010) 11 SCC 661: Compassionate Appointment is a Concession, Not a Right. This ruling clarifies that compassionate appointment is an exception to the normal rules of recruitment. Because it is a concession offered by the employer, the employer retains the right to modify or even withdraw the scheme based on its policy and financial capacity.

- Dinesh Kumar Kashyap v South East Central Railway, (2019) 12 SCC 798: Reasonable Expectation of Appointment. While successful candidates have no vested right, the court held that they possess a reasonable expectation. The employer cannot act arbitrarily and must provide justifiable, non-arbitrary reasons for deciding not to fill available vacancies from a prepared select list.

- Ashwani Kumar v State of Bihar, (1997) 2 SCC 1: Appointment Requires an Existing Vacancy. This case reinforces the foundational rule that an appointment is legally impossible without a sanctioned post or vacancy to fill. There can be no employee without a post.

Having established the nature of a candidate’s right to be considered for a post, we must now identify the specific authority responsible for making a valid appointment.

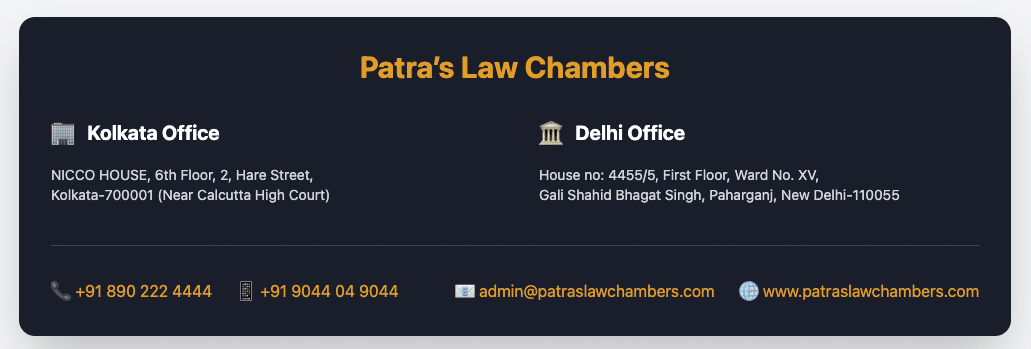

Credits & Consultation

This article is credited to and authored by the legal team at Patra’s Law Chambers.

If you are facing legal challenges regarding service law, public appointments, or administrative disputes, you may consult our experts for professional legal guidance. We specialize in matters pertaining to Service Rules (SR) and Constitutional mandates across Kolkata and Delhi.

Contact Patra’s Law Chambers:

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

——————————————————————————–

2. The Appointing Authority: Powers and Duties

2.1. Strategic Overview

Identifying the correct ‘Appointing Authority’ is a matter of substantive legal importance, not a mere procedural formality. The entire validity of an appointment hinges on it being made by the competent authority. This determination has profound consequences later in an employee’s career, creating a critical tension between administrative procedure and constitutional rights. The identity of the appointing authority is directly linked to the protections against dismissal and removal under Article 311, which stipulates that an employee cannot be removed by an authority subordinate to the one that appointed them.

2.2. Analysis of Core Principles

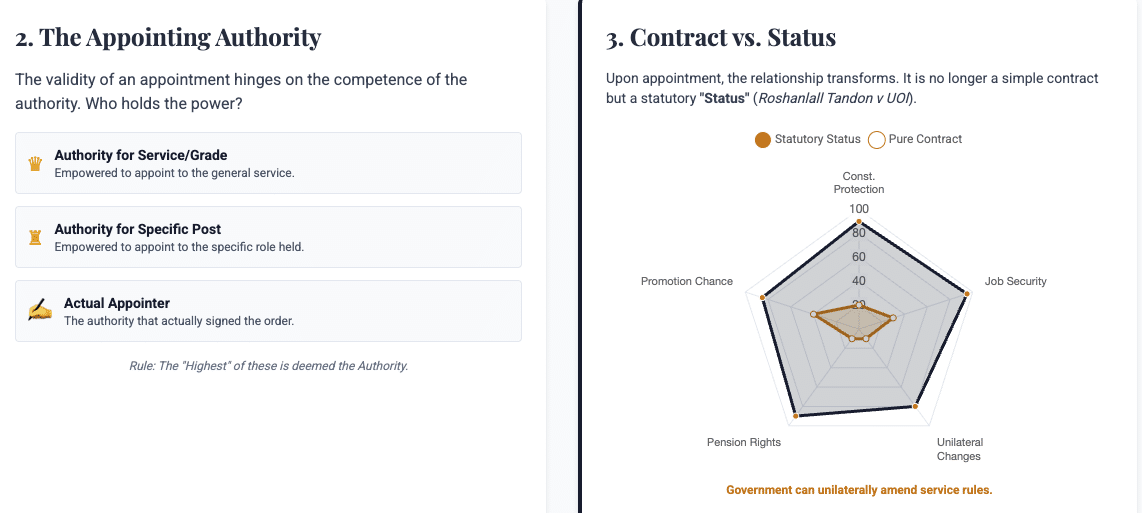

- Defining the Appointing Authority: The term ‘Appointing Authority’ is precisely defined in service rules, such as the Central Civil Services (Classification, Control & Appeal) Rules, 1965. In relation to a Government servant, it is the authority that satisfies one of the following criteria, with the rule stating that “…whichever Authority is the highest authority” shall be deemed the Appointing Authority:

- The authority empowered to make appointments to the service or grade.

- The authority empowered to make appointments to the specific post held by the government servant.

- The authority which actually appointed the government servant.

- For a permanent employee, the authority which first appointed them to any permanent post.

- Powers and Limitations: The actions of the appointing authority are governed by several key principles:

- Independent Application of Mind: The appointing authority must exercise its own judgment and cannot act mechanically. Even when presented with a select list from a recruitment body, it must apply its mind independently before making the final appointment.

- Selection by PSC is Recommendatory: A recommendation from a Public Service Commission (PSC) is not binding on the government. It does not create an automatic right to appointment for the selected candidate. A vested right is acquired only after the government formally accepts the recommendation and issues an appointment order.

- Delegation of Power: The power of appointment can be delegated to a subordinate authority, provided there is no statutory bar against such delegation. In such cases, the delegatee becomes the legally recognized appointing authority for that post.

- Appointments by Incompetent Authority: An appointment made by an authority that lacks the legal competence to do so is invalid and void from its inception (void ab initio). Such a fundamental defect cannot be cured by the subsequent ratification or approval of the competent authority.

2.3. Landmark Case Law

- State of Assam v Kripanath Sanna, AIR 1967 SC 459: The Designated Officer is the Appointing Authority. The court held that even if a statute requires an officer to make an appointment on the advice of a higher body, the officer designated by the statute remains the legal appointing authority.

- T Cajee v U Jomanik Siem, AIR 1961 SC 276: Power of Removal Vests with the Appointing Authority. This case established that the authority that confirms an appointment (in this instance, the District Council) becomes the appointing authority with the corresponding power of removal, reinforcing the critical link between appointment and the protections under Article 311.

- VC, Banaras Hindu University v Shrikant, (2006) 11 SCC 42: Nullity Cannot be Cured by Approval. If an initial appointment order is a nullity because it was made by an incompetent authority, it cannot be validated or legitimized by the subsequent approval of the competent authority. The defect is incurable.

Once a valid appointment is made by the competent authority, it creates a unique legal relationship. But is this relationship governed by the mutual consent of a contract, or by a set of duties imposed by public law? The next section explores this fundamental distinction.

——————————————————————————–

3. The Legal Character of an Appointment: Contract vs. Status

3.1. Strategic Overview

The legal character of a public appointment is a sophisticated concept that evolves from a simple contractual agreement into a complex legal ‘status’. This transition is a central tenet of service law, and its understanding is essential to grasp the key tension between private contract law and public administrative law. This shift explains why the government possesses the unique power to unilaterally alter the service conditions of its employees—a power fundamentally at odds with the principles of a standard private contract, which can only be modified by mutual consent.

3.2. Analysis of the “Status” Doctrine

- Contractual Origin: Government service originates in contract. It begins with the standard elements of contract law: an offer of appointment is made by the state, and it is accepted by the individual.

- Transition to Status: Upon appointment, the relationship undergoes a fundamental transformation. The initial contract is subsumed by a new legal relationship defined by ‘status’. The pivotal judicial pronouncement on this doctrine comes from Roshanlall Tandon v UOI, which states:

- Implications of Status: The acquisition of ‘status’ by a public servant has several critical legal consequences:

- The employee’s service conditions are governed by statutory rules and regulations, not merely by the terms of the original appointment letter.

- The Government has the power to unilaterally amend these rules and conditions of service, and such amendments are binding on the employee.

- The employee gains the protection of the Constitution, particularly under Articles 309, 310, and 311, which safeguard their tenure and prescribe procedures for disciplinary action.

- This acquisition of status and its attendant constitutional protections is contingent upon the appointment being made in conformity with the constitutional scheme (Articles 14, 16) and statutory rules. If the initial appointment was fundamentally improper, the relationship may remain purely contractual, and the employee will not gain these protections.

- Terms in the initial contract that are found to be unfair, unconscionable, or against public policy (often termed “contracts of adhesion”) can be struck down by courts, even if the employee had agreed to them.

3.3. Landmark Case Law

| Case | Core Principle and Significance |

| Roshanlall Tandon v UOI, AIR 1967 SC 1889 | Established the “Status” Doctrine. This case is the locus classicus for the principle that once appointed, a government servant’s relationship with the government is governed by status, not contract, allowing the state to unilaterally change service conditions. |

| Central Inland Water Transport Corp Ltd v Brojonath Ganguly, AIR 1986 SC 1571 | Limited the Power of Unconscionable Contract Terms. This case established that even within a public service contract, terms that are wildly unfair, unconscionable, or against public policy (like a “Henry VIII clause” allowing termination without reason) are void, even if the employee agreed to them. |

The status acquired upon appointment governs the conditions of service, which leads directly to the question of the duration, or ‘tenure’, of the office held.

——————————————————————————–

4. Tenure of Office: The Pleasure Doctrine and Its Limits

4.1. Strategic Overview

The ‘pleasure doctrine’ is a fundamental, yet often misunderstood, principle governing the tenure of government servants. This section explores the central constitutional conflict between the state’s need for administrative control, embodied in the pleasure doctrine under Article 310, and the individual’s right to due process, secured by the powerful safeguards in Article 311. Understanding this balance is key, as these safeguards ensure that the doctrine is not an instrument of arbitrary power but is instead a constitutional arrangement balanced by robust procedural protections for the civil servant.

4.2. Analysis of the Pleasure Doctrine

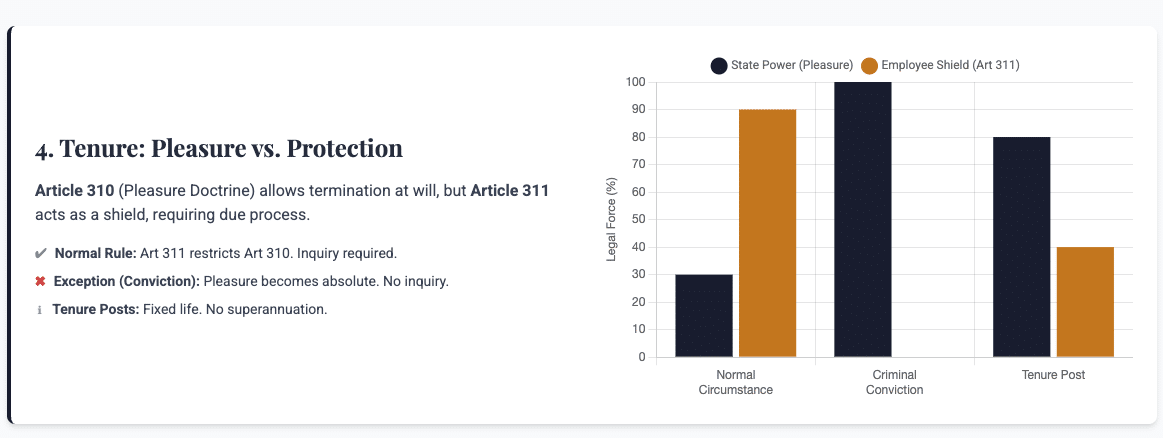

- Constitutional Basis: Article 310(1) of the Constitution of India establishes that civil servants hold office “during the pleasure of the President” (for Union services) or “during the pleasure of the Governor” (for State services). This doctrine is derived from English common law, where the Crown can terminate service at will. However, its application in India is significantly different and is constrained by the Constitution itself.

- Key Propositions from UOI v Tulsiram Patel: The modern scope of the pleasure doctrine was authoritatively settled by the Constitution Bench in the Tulsiram Patel case. The key propositions are:

- Subject only to the Constitution: Unlike in the United Kingdom, where the doctrine is subject to laws made by Parliament, in India, the pleasure of the President or Governor is subject only to express provisions of the Constitution.

- Article 311 is the Primary Fetter: Article 311, which provides crucial procedural safeguards against dismissal, removal, or reduction in rank, is the most significant “express provision” that limits the exercise of pleasure under Article 310. Article 311 functions as a proviso to Article 310. However, when the exceptions in the second proviso to Article 311(2) are triggered (e.g., conviction on a criminal charge), the pleasure of the President/Governor becomes “free of the restrictions placed upon it,” unleashing the doctrine in those specific circumstances.

- Article 309 is Subordinate: Rules made under Article 309 (which govern service conditions) cannot restrict or override the pleasure doctrine. This is because Article 309 is itself “subject to the provisions of this Constitution,” which includes Article 310.

- Tenure Posts: A ‘tenure post’ is a permanent post that an individual is appointed to hold for a fixed, limited period, as opposed to a regular permanent post held until the age of superannuation. The holder of a tenure post does not superannuate; their service simply ends upon the completion of their tenure. This fixed tenure cannot be curtailed arbitrarily, and any premature termination must be for justifiable grounds and follow the due process of law.

4.3. Landmark Case Law

- Moti Ram Deka v General Manager, NEF, Railways, (1964): Major Restriction on the Pleasure Doctrine. In this seminal decision, a seven-judge bench struck down railway service rules that allowed for the termination of a permanent servant’s employment on simple notice without cause. The Court held that such termination amounts to “removal” and therefore must comply with the procedural safeguards of Article 311(2). This judgment significantly limited the state’s power to terminate services arbitrarily.

- UOI v Tulsiram Patel, (1985): Clarified the Modern Scope of the Doctrine. This Constitution Bench decision provided the definitive modern interpretation of the pleasure doctrine. It affirmed that Article 311 acts as a restriction on Article 310. However, it also clarified that when the exceptions listed in the second proviso to Article 311(2) are applicable (e.g., termination following a conviction on a criminal charge), the pleasure of the President/Governor becomes absolute and effective, and the procedural safeguards of an inquiry do not apply.

- Dr LP Agarwal v UOI, (1992): Tenure Post Jurisprudence. This case clarified the legal nature of a tenure post. The Supreme Court held that the concept of superannuation is alien to a tenure appointment. Such a post has a fixed lifespan and cannot be cut short by premature retirement. However, the tenure can be curtailed for justifiable grounds after following the due process of law.

The duration of an appointment is thus determined by the pleasure doctrine, constitutional safeguards, and the specific nature of the post. How, then, do the legal rights differ between these distinct types of appointments?

——————————————————————————–

5. The Spectrum of Appointments: From Permanent to Ad Hoc

5.1. Strategic Overview

The rights, security, and legal protections afforded to a public servant are directly determined by the specific nature of their appointment. The distinctions between terms like ‘permanent’, ‘temporary’, ‘officiating’, and ‘ad hoc’ are not merely semantic; they carry profound legal consequences for an employee’s tenure, seniority, and constitutional protection. This section will detail these different categories of appointment and explain their distinct legal characteristics, which are a frequent source of service law disputes.

5.2. Analysis of Appointment Types

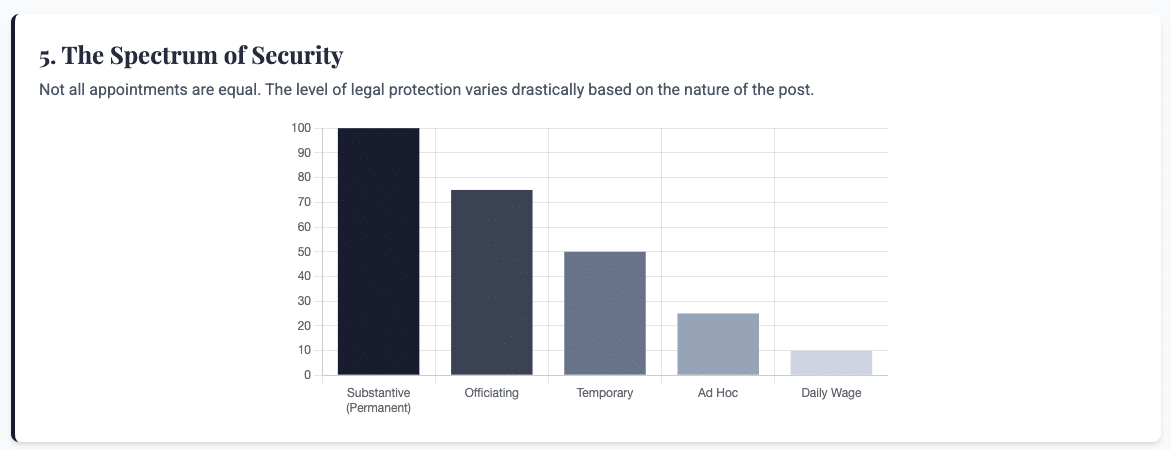

- Substantive Appointment to a Permanent Post:

- Definition: An appointment made in a substantive capacity to a permanent post, which is a post sanctioned without a specified time limit.

- Legal Consequence: This is the most secure form of public employment. It confers a ‘lien’ on the post, which is the employee’s title to hold that post substantively. This right can only be terminated upon reaching the age of superannuation, through compulsory retirement, or via termination for cause after following the due process prescribed under Article 311.

- Appointment to a Temporary Post:

- Definition: An appointment to a post that has been sanctioned only for a limited period.

- Legal Consequence: The employee acquires no right to the post itself. Their tenure is inherently limited by the duration for which the post is sanctioned, and the employment ceases when the post is abolished.

- ‘Officiating’ vs. ‘Temporary’ Appointment:

- Contrast: The Supreme Court in Arun Kumar Chatterjee v South Eastern Railway distinguished these two terms clearly.

| Officiating | Temporary |

| A servant with a substantive post is appointed to a higher post, but not substantively (e.g., in a temporary vacancy). They retain their lien on the lower post. | A person is appointed to the civil service for the first time on a non-permanent basis, with no right to the post. |

- Ad Hoc Appointment:

- Definition: A stop-gap, fortuitous, or purely temporary appointment made for a particular purpose or in an emergency, which is, by its nature, not made in accordance with the provisions of regular recruitment rules.

- Legal Consequence: An ad hoc appointment does not confer any indefeasible right to the post. The Supreme Court, in cases like J&K Public Service Commission v Narinder Mohan, has held that such appointments, often made as “back door entries,” are antagonistic to the principle of regular recruitment and cannot be used as a basis for claiming regularization.

- Appointment of Daily Wagers:

- Definition: Persons engaged on a daily wage basis who do not hold a post within a sanctioned cadre of the service.

- Legal Consequence: As established in the landmark case of Secretary, State of Karnataka v Uma Devi (3), such engagements are not appointments to a post according to the rules. Daily wagers have no legal right to permanency or regularization, except for the one-time exception outlined in that specific judgment for those who had worked for over ten years without the cover of court orders.

Beyond these standard categories, the law recognizes certain special appointments made on an exceptional basis, which operate outside the normal rules of recruitment.

——————————————————————————–

6. Exceptions to the Rule: Compassionate and Compensatory Appointments

6.1. Strategic Overview

Compassionate and compensatory appointments are recognized exceptions to the constitutional mandate of open competition and merit-based selection enshrined in Articles 14 and 16. They are not regular sources of recruitment. Because they carve out an exception to a fundamental constitutional principle, they are governed by a strict set of judicially-defined rules and guidelines. This ensures that these provisions are used for their intended, narrow purpose—to provide immediate relief in a crisis—and are not misused as an alternative, backdoor channel for public employment.

6.2. Compassionate Appointments: Rationale and Guiding Principles

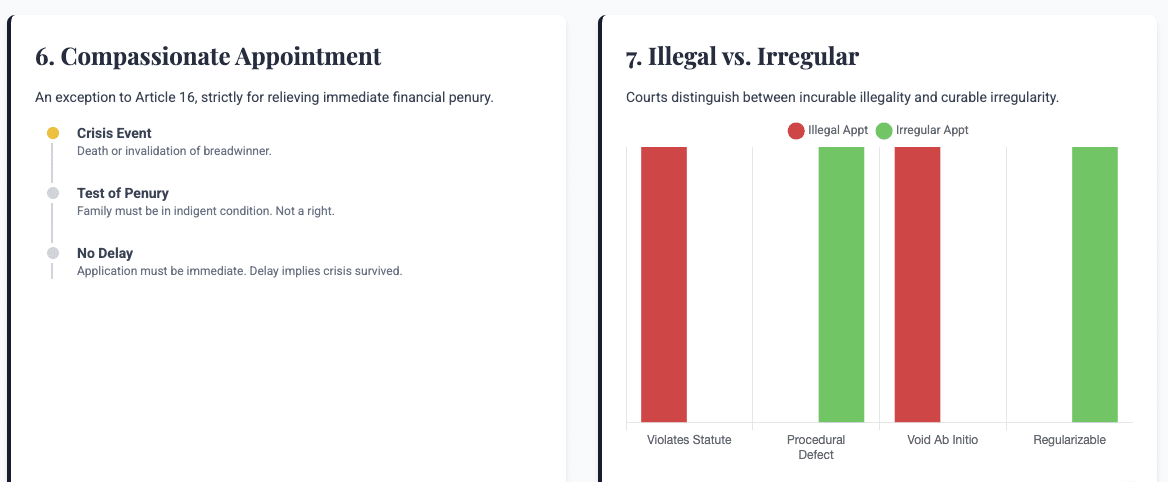

- Core Objective: The sole and exclusive objective of a compassionate appointment is to provide immediate succour to a family that has been plunged into penury and destitution by the untimely death or medical invalidation of its sole breadwinner. The plight of a family whose member is medically incapacitated is sometimes considered even more critical. It is not intended to provide a post for a post or to be a form of inheritance.

- Governing Principles: The Supreme Court has laid down essential principles that govern the grant of compassionate appointments:

- Not a Vested Right: It is a concession, not a right. It cannot be inherited or claimed as a matter of course, especially after the immediate financial crisis has passed.

- Penury is the Test: The primary and overriding consideration is the financial condition of the deceased’s family. If the family is not in an indigent state, the appointment should be denied.

- Must Adhere to a Scheme: Appointments can only be made strictly in accordance with a valid, existing scheme framed by the employer. Courts cannot order appointments outside the terms of such a scheme.

- Delay is Fatal: As the purpose is to overcome an immediate crisis, a long delay in either applying for or claiming the appointment is a valid ground for rejection. The passage of time indicates that the family has been able to survive the crisis (State of J&K v Sajad Ahmed Mir).

- Not an Alternative Recruitment Channel: This is an exception and cannot be treated as a parallel or alternative mode of recruitment to bypass the regular, merit-based selection process.

- Applicable Scheme: The scheme that was in force at the time of the employee’s death is the one that governs the claim for compassionate appointment.

6.3. Compensatory Appointments

Compensatory appointments for individuals whose land has been acquired by the state (“landlosers”) are purely a matter of state policy and benevolence. There is no inherent or constitutional right to such an appointment in addition to the statutory compensation received under land acquisition laws.

6.4. Landmark Case Law

- Umesh Kr. Nagpal v State of Haryana, (1994): The Definitive Guidelines. This case authoritatively laid down the foundational principles for compassionate appointments. The Court held that the object is to tide over a sudden crisis; the financial destitution of the family is the paramount consideration; and it is not a right to a post-for-post replacement. Such appointments should generally be limited to lower-level posts (Class III or IV).

- Haryana State Electricity Board v Hakim Singh, (1997): Reiterated the Core Rationale. This case emphasized that the object of the scheme is to provide ameliorating relief to a family in distress and should not be treated as an alternative or parallel mode of recruitment to public employment.

From appointments that are exceptions to the rule, we now turn to appointments that are legally defective from their very inception.

——————————————————————————–

7. Defective Appointments: Illegality, Invalidity, and Cancellation

7.1. Strategic Overview

The law draws a critical distinction between different types of defective appointments. An ‘illegal’ appointment, which is made in contravention of mandatory statutory provisions, is treated as void from the start (void ab initio). In contrast, an ‘irregular’ appointment, which suffers from a procedural or curable defect, may be capable of being regularized. This distinction is crucial for determining the legal consequences, particularly whether the principles of natural justice must be followed before an appointment is cancelled, and it underscores the judicial maxim that “Those who come by back door should go through that door.”

7.2. Analysis of Core Principles

- Illegal vs. Irregular Appointments:

| Illegal Appointment | Irregular Appointment |

| An appointment made in violation of mandatory statutory provisions (e.g., lacking minimum essential qualification). It is void ab initio. | An appointment with a procedural defect or one that deviates from a non-mandatory process. |

| Cannot be regularized. “An appointment made in violation of the mandatory provisions of the statute… would be wholly illegal. Such illegality cannot be cured by taking recourse to regularisation.” | May be regularized. If the defect is curable, the appointment can potentially be validated or regularized by the competent authority. |

- Grounds for Cancellation: An appointment may be cancelled on several grounds, including:

- The appointment was secured through fraud or misrepresentation.

- The appointee lacked the essential, mandatory qualifications prescribed for the post.

- The entire selection process was tainted by mass malpractices, corruption, or nepotism.

- Appointments were made in excess of advertised posts.

- The candidate willfully suppressed material facts, such as involvement in a criminal case, in the application or verification form.

- The Role of Natural Justice (Audi Alteram Partem): The principle of audi alteram partem (hear the other side) is a cornerstone of administrative law. Its application in cancellation cases depends on the nature of the defect.

- When Applicable: As a general rule, natural justice must be observed before cancelling an appointment that has conferred a vested right on an individual. As established in Shridhar v Nagar Palika, Jaunpur, an opportunity to be heard must be given before such a right is taken away.

- When Not Applicable: The requirement of a hearing is dispensed with in certain situations where the appointment is fundamentally void or fraudulent. These exceptions include:

- The appointment was obtained through fraud.

- The appointment was based on forged documents.

- The appointment was void ab initio (e.g., made by an incompetent authority or without the essential qualifications).

- The entire selection process was cancelled due to widespread illegality, making it impractical to give individual hearings to all affected candidates, as held in UOI v O Chakradhar.

The cancellation of an appointment is an administrative action, which naturally raises the question of the judiciary’s power to review such decisions.

——————————————————————————–

8. Judicial Review of Appointments

8.1. Strategic Overview

While the appointment of public servants is an executive function, it is not immune from judicial scrutiny. The judiciary plays a vital role as the guardian of the rule of law. However, its role is not to act as a super-selection committee or to substitute its own wisdom for that of the appointing authority. The purpose of judicial review is to ensure that the appointment process—a matter of immense public interest—is fair, non-arbitrary, and complies with all constitutional and statutory mandates.

8.2. Scope and Limitations of Judicial Review

- Grounds for Interference: A court can judicially review and interfere with an appointment decision primarily on the following grounds:

- Illegality: The appointment or the process followed contravenes statutory rules or constitutional provisions like Articles 14 and 16.

- Mala Fides: The decision was motivated by malice, bias, or an oblique motive.

- Non-application of Mind: The appointing authority failed to consider relevant factors, took into account irrelevant considerations, or acted mechanically.

- Arbitrariness: The decision is so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could have ever reached it (the “Wednesbury unreasonableness” standard).

- Deference to Expert Opinion: Courts exercise a significant degree of restraint when reviewing the decisions of expert bodies and selection committees. The court’s role is to ensure the decision-making process was fair and lawful, not to re-evaluate candidates and substitute its own opinion for that of the experts. As the Supreme Court has cautioned, administration should not be thwarted in making appointments just because a particular outcome “displeases judicial relish.”

- Public Interest Litigation (PIL): Public Interest Litigation can be a tool to challenge high-level appointments where the integrity of a public institution is at stake. This was demonstrated in the case of Centre for PIL v UOI, which challenged the appointment of the Central Vigilance Commissioner (CVC) on the grounds that relevant adverse material was not properly considered by the high-powered selection committee.

8.3. Landmark Case Law

- Dr MC Gupta v. Dr Arun Kumar Gupta, (1979): Defined the Scope of Judicial Review. This case established the core principle that courts should be slow to interfere with the opinion of expert selection bodies unless there are clear allegations of mala fides or a manifest contravention of binding rules. The court’s function is to enforce the rule of law, not to second-guess the expert assessment of a candidate’s suitability.

- State of UP v Rajkumar Sharma, (2006) & UOI v Kartick Chandra Mondal, (2010): No Negative Equality under Article 14. These cases reinforce the vital principle that Article 14 does not permit “negative equality.” If the state mistakenly or illegally appointed an unqualified person in the past, a court cannot compel it to perpetuate that same mistake by appointing another unqualified person. An illegality cannot be used to claim a right to equal treatment in illegality.

In conclusion, the law of appointment represents a carefully calibrated balance between the executive’s discretion to manage public services and the judiciary’s constitutional duty to ensure that such discretion is exercised in conformity with the rule of law.

Credits & Consultation

This article is credited to and authored by the legal team at Patra’s Law Chambers.

If you are facing legal challenges regarding service law, public appointments, or administrative disputes, you may consult our experts for professional legal guidance. We specialize in matters pertaining to Service Rules (SR) and Constitutional mandates across Kolkata and Delhi.

Contact Patra’s Law Chambers:

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055