- Transfer is an incident of public service, negating the need for employee consent for intra-cadre moves.

- Legal definition requires movement outside the headquarters; posting within headquarters is not a transfer.

- Court will strike down transfers executed for political interference or to accommodate another person.

- Deputation differs: it is contractual and requires the employee's consent.

- Transfers must be exercised bona fide for administrative exigency; malice in fact or law invalidates orders.

- Valid transfers must preserve an employee's status, seniority, and not amount to demotion disguised as transfer.

- Employees must generally report first, grieve later; noncompliance risks disciplinary action unless the order is void.

Law of Transfer In Government Service

-

Creditor and contributor of this article:

Patra’s Law Chambers:

About Us:

Patra’s Law Chambers is a law firm with offices in Kolkata & Delhi, offering comprehensive legal services across various domains. Established in 2020 by Advocate Sudip Patra (Advocate, Supreme Court of India & Calcutta High Court) an alumnus of the Prestigious Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, IIT Kharagpur ,with Post Graduate diploma in Business Law from IIM Calcutta, the firm specializes in Civil, Criminal, Writs,High Court Matters, Trademark, Copyright, Company, Tax, Banking, Property disputes, Service law, Family law, and Supreme Court matters.You can know more about us in here

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid

Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +91 890 222 4444/ +91 7003 715 325

Introduction

In the intricate architecture of public administration, the management of human resources constitutes a cornerstone of effective governance. The state, functioning not merely as a sovereign but as a colossal employer, relies on the fluidity and adaptability of its workforce to meet the dynamic exigencies of public service. Within this framework, the “Law of Transfer” emerges as a critical, albeit contentious, domain of service jurisprudence. It is the legal interface where the sovereign prerogatives of the state intersect with the constitutional and statutory rights of the individual civil servant.

The concept of transfer is deceptively simple in its administrative definition—the movement of an employee from one post to another. However, in the realm of law, it acts as a fulcrum balancing two competing interests: the “Exigency of Administration,” which demands that the right officer be placed at the right place at the right time, and the “Security of Tenure,” which protects the employee from arbitrary displacement, harassment, and the erosion of service conditions.

This treatise provides an exhaustive analysis of the legal principles, judicial doctrines, and statutory rules governing the transfer of public servants. Drawing upon a wealth of judicial precedents, including landmark judgments from the Supreme Court and various High Courts, this report seeks to demystify the complex legal landscape of employee mobility. It explores the foundational principles that define transfer as an “incident of service,” distinguishes it from related concepts like deputation, examines the scope and limitations of the employer’s power, and elucidates the grounds upon which the judiciary may intervene in what is essentially an administrative function.

Through a detailed examination of the document ‘Law of Transfer in Public Service’ and an analysis of the cited case laws, this report serves as a definitive guide for legal practitioners, administrators, and public servants alike, offering a nuanced understanding of how the law seeks to prevent the abuse of power while upholding the efficiency of public administration.1

Part I: The Foundational Principles of Employee Transfer

To understand the superstructure of transfer law, one must first inspect its foundation. The legal framework governing transfers is not merely a collection of rules; it is built upon specific jurisprudential doctrines that define the relationship between the state and its servants.

1.1 The Legal Definition and Spatial Dynamics

Understanding the complex legal framework begins with grasping the fundamental nature of the concept itself. In the general parlance of service, a “transfer” is simply a change of an employee’s place of employment within an organization. It is an inherent and accepted feature of public service, and this foundational principle shapes the entire legal doctrine surrounding it.1

However, the law requires precision. Service rules often provide a specific legal definition. For instance, Supplementary Rule 2(18) of the Fundamental Rules, which governs the service conditions of Central Government servants, defines transfer with a focus on spatial movement. It characterizes transfer as the movement of an employee from one “headquarters station” to another, either to take up the duties of a new post or as a consequence of a change in their headquarters.1

This definition introduces a critical legal distinction: the concept of the “Headquarters.”

The Doctrine of Headquarters: UM Anigol v State of Mysore

The significance of the “headquarters” concept was judicially illuminated by Justice Jagannatha Shetty in the case of UM Anigol v State of Mysore. In interpreting Rule 8(19) of the Mysore Civil Services Rules—which is nearly identical to the Central Fundamental Rule 2(18)—the court established a vital boundary for what constitutes a transfer.

The court held that an employee is only considered “transferred” in the eyes of the law when they are posted to a location outside their former headquarters. This distinction is paramount. A simple change of post within the same headquarters—moving from one desk to another, or one building to another within the same municipal limit—does not legally constitute a transfer. It is merely a change of posting. This distinction affects the employee’s entitlement to transfer grants, joining time, and other allowances associated with relocation.1

1.2 The Doctrine of “Incident of Service”

If there is a single “Grundnorm” in the law of transfer, it is the principle that transfer is an “incident of public service.” This legal construction is the basis for negating the requirement of consent; a person is presumed to have accepted this reality upon joining public service with the knowledge that transfer is an established feature.1

The “Implied Condition” Theory

The courts have oscillated between describing transfer as an “implied condition” and an “incident.”

- Seshrao Nagorao Umap v State of Maharashtra: The Bombay High Court described transfer as an “implied condition of service.” This suggests that even if the written contract or appointment letter is silent on the matter of transfer, the condition is implied by the very nature of government employment. The state cannot function if its employees are immobile fixtures.1

The “Incident” Terminology

- B Varadha Rao v State of Karnataka: The Supreme Court refined the terminology, clarifying that “incident of service” is the more precise legal description. The term “incident” connotes an “inbuilt component” of the total concept of public service. It is inseparable from the status of being a government employee.1

This doctrine has profound implications:

- No Vested Right: As affirmed in B Varadha Rao, no employee has a vested right to remain in a particular post. Unless the appointment is to a specific, non-transferable post (which is rare), the employee’s lien is on a post in the cadre, not on a specific geographical location.1

- Implicit Acceptance: By accepting the offer of employment, the public servant is deemed to have consented to the liability of transfer.

- Judicial Non-Interference: Because it is a normal feature of service, courts are reluctant to treat a transfer order as a cause of action unless it violates a specific statutory protection.

1.3 The Limitation on “Incident of Service”

While the power to transfer is an incident of service, it is not an absolute license for the state to act arbitrarily. The Supreme Court has placed a crucial caveat on this power: the “Public Interest.”

- TSR Subramanian v UOI: In this landmark judgment, the Supreme Court observed that frequent and arbitrary transfers, often driven by political considerations rather than administrative needs, are “deleterious to good governance.” While the power exists, its exercise must be aligned with the public interest. A transfer that serves the whims of a politician rather than the needs of the administration is contrary to the public interest and thus susceptible to legal challenge.1

1.4 Transfer Simpliciter vs. Recruitment by Transfer

It is also vital to distinguish a “transfer simpliciter”—which is a routine posting to a similar post within the same cadre—from “recruitment by transfer.” The latter is a distinct mode of selection and recruitment to a service. When an employee undergoes “recruitment by transfer,” they are effectively entering a new service. This results in the employee losing their lien (the right to hold a post) in their previous position and acquiring a new lien in the new service. This is not a mere administrative movement but a change in the fundamental employment contract.1

Part II: The Dichotomy of Displacement – Transfer vs. Deputation

A frequent source of litigation in service matters arises from the confusion between “Transfer” and “Deputation.” While both involve the movement of personnel, they are jurisprudentially distinct concepts governed by different rules, particularly regarding the element of consent.

It is strategically important for both employers and employees to understand these fundamental differences. The legal basis for each, the implications for an employee’s service conditions, and, most critically, the requirement of consent, are entirely distinct.1

2.1 The Concept of Deputation

Deputation is not merely a transfer; it is a “lending” of services. It involves a tripartite agreement between:

- The Lending Authority: The parent department where the employee holds a substantive lien.

- The Borrowing Authority: The foreign organization or department that utilizes the employee’s services for a specific period.

- The Employee: The individual whose services are being lent.

The key distinctions, articulated by Justice D.A. Desai in the Bhagwati Prasad case and further clarified in Parasha Rani v State of Madhya Pradesh, highlight the contractual nature of deputation versus the unilateral nature of transfer.1

2.2 The Critical Role of Consent

The most significant legal watershed between the two concepts is the requirement of consent.

- Transfer: The general rule is that an employee’s consent is not necessary for a transfer within their cadre. It is an exercise of the employer’s prerogative.1

- Deputation: Consent is mandatory. The Supreme Court in Jawaharlal Nehru University v KS Jawalkar made it clear that no employee can be transferred without their consent from one employer to another. The rationale is rooted in the law of contract: an employee enters into a contract of service with a specific employer (e.g., the State Government). The employer cannot unilaterally assign that contract to a third party (e.g., a University or a Public Sector Undertaking) without the employee’s agreement.1

2.3 Structural Differences

The following comparative analysis synthesizes the distinctions established in cases like Bhagwati Prasad and Parasha Rani:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Transfer and Deputation

| Feature | Transfer | Deputation |

| Scope of Movement | Movement to an equivalent post within the same parent department or cadre. | Movement to a service outside the parent department/cadre, often for a temporary duration. |

| Requirement of Consent | Not generally required. It is an incident of service. | Essential. The employee must agree to leave their parent cadre. |

| Nature of Post | Must be an equivalent post in terms of status and responsibility. | The post need not be strictly equivalent. It often carries a “deputation allowance.” |

| Career Progression | The employee continues to gain seniority within the same list. | The employee continues to look to their parent cadre for promotion and confirmation. |

| Source of Power | An inherent power of the employer, rooted in implied conditions of public service. | Arises from a tripartite agreement between the lending employer, borrowing employer, and employee. |

| Legal Basis | Unilateral Administrative Order. | Contractual/Consensual Arrangement. |

1

This distinction protects employees from being forcibly exiled to organizations where they may lose their seniority or statutory protections. A government servant cannot be forced to become an employee of a corporation, even if that corporation is state-owned, without their consent.

Part III: The Legal Basis and Scope of the Power to Transfer

Having defined the concept, we must examine the source of the authority. Does the government need a specific law to transfer an officer, or is the power inherent?

3.1 The Theory of Inherent Power

The power to transfer is considered an inherent authority of the state as an employer. It is so fundamental to the management of public service that it is regarded as an “implied condition of service,” meaning it exists even in the absence of explicit rules or contractual terms to that effect.1

The Supreme Court and various High Courts have consistently held that the power to transfer exists even without express service rules because it is an “incident of Government service.” In B Varadha Rao v State of Karnataka, the Supreme Court established that this power is an inbuilt component of the concept of public service. Because a person joins public service with the knowledge that transfer is an established feature, the need for their consent is negated.1

This implies that a government servant cannot challenge a transfer order merely on the ground that there is no specific rule in their service code empowering the government to transfer them. The power is assumed to exist unless explicitly prohibited.

3.2 Limitations: The “Nature of Recruitment” Test

While the existence of the power is rarely in doubt, its extent can be limited by the employee’s specific terms of appointment. The principle, articulated in SK Srivastava v UOI, is that the range of transferability depends on the nature of the recruitment.1

- All India Service: If an officer is recruited to an All India Service (like the IAS or IPS), their liability to serve extends to the entire territory of India.

- State Service: If recruited to a State Civil Service, the liability is restricted to the state.

- District Cadre: If recruited to a district-level cadre, the power to transfer is generally limited to that district.

The Single-Post Exception: Prem Behari Lal Saxena

The limitation of power is most visible in cases where recruitment is to a specific, isolated post. This is illustrated in the case of Prem Behari Lal Saxena.

In this case, an individual was recruited specifically for the post of Anesthetist in a state hospital in Kanpur. The government attempted to transfer him to a hospital in Varanasi. The court sustained his challenge, quashing the transfer order. The reasoning was precise: his appointment was to an individual post attached to a specific hospital, not to a state-wide cadre of Anesthetists. Therefore, the normal “implied liability” to transfer could not be inferred. He held a specific office, not a general rank in a mobile service.1

3.3 The Competent Authority

It is crucial to differentiate between the existence of the power to transfer and the propriety of its exercise. The competent authority to exercise this power is typically the appointing authority or an officer to whom such power has been delegated.

However, exceptional circumstances exist where the power shifts. For instance, the Election Commission of India, under Article 324 of the Constitution, possesses the power to transfer officials to ensure free and fair elections. During the election period, the Commission can direct the transfer of District Magistrates or Police Superintendents, overriding the normal administrative hierarchy.1

Part IV: The Doctrine of Bona Fide Exercise of Power

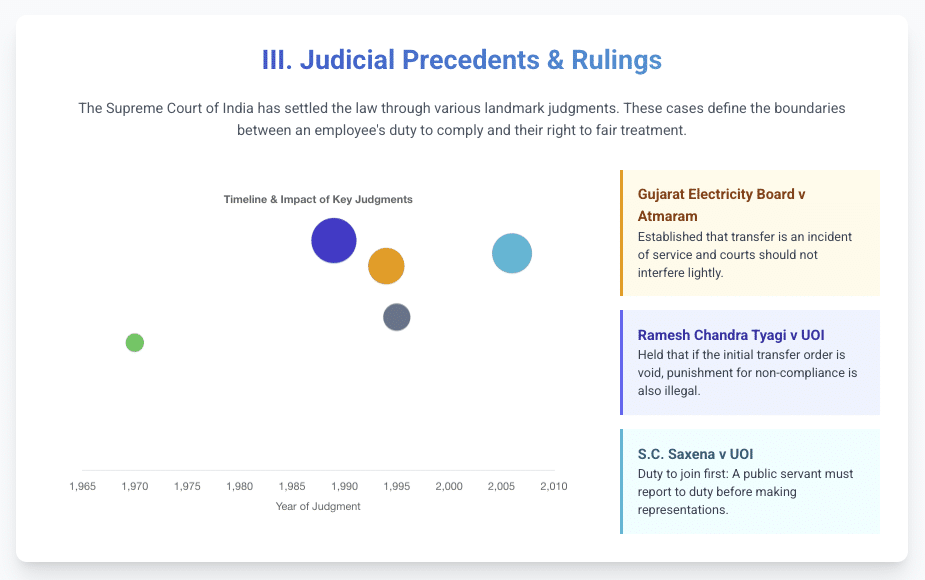

The existence of an inherent power is not a license for its arbitrary use. Administrative law demands that this power, like any other, be exercised bona fide—that is, fairly, reasonably, and for genuine administrative needs. It cannot be used for extraneous, irrelevant, or malicious reasons. An order that fails this test is considered a “mala fide” or “colorable” exercise of power and is liable to be invalidated by the courts.1

4.1 Defining Malice in the Context of Transfer

“Mala fides” (bad faith) is the most common ground for challenging a transfer order. However, it is a complex legal concept with two distinct dimensions: Malice in Fact and Malice in Law.

Malice in Fact (Personal Malice)

This involves personal ill-will, spite, or a corrupt motive on the part of the authority issuing the order. It occurs when an officer is transferred because the superior holds a personal grudge against them.1

- Evidentiary Burden: Proving malice in fact is notoriously difficult. The burden of proof lies heavily on the petitioner (the employee), who must provide a “firm foundation of facts.” Vague insinuations are insufficient for a court to infer personal spite.

Malice in Law (Colorable Exercise of Power)

This is a broader and more jurisprudential concept. It does not require proof of personal animosity. As explained by Justice Krishna Iyer in State of Punjab v Gurdial Singh, an action is invalidated by legal malice when power is used for a purpose other than the one for which it was entrusted.

If a power (transfer) is conferred for the purpose of administrative efficiency, but is used for a different purpose (e.g., to punish an employee, or to vacate a house for a favorite), it constitutes a “fraud on power.” The action is void not because the officer is “evil,” but because the action falls outside the scope of the legal power granted.1

4.2 The “Exigencies of Administration”

The primary justification—and the only valid legal purpose—for a transfer is the “exigencies of administration.” This refers to the needs and demands of running a good and efficient public service. The government is generally considered the best judge of these needs (reference KB Shukla v UOI).1

However, the courts have stepped in to define what constitutes a valid exigency versus an invalid one.

Valid Exigency: TD Subramaniam v UOI

In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the transfer of a technically competent officer who was found to lack tact in managing his staff. The officer argued that he was competent and efficient. The Court, however, reasoned that “efficiency” in public administration includes the ability to handle staff and maintain harmony. A brilliant officer who causes constant friction is an administrative liability. Therefore, transferring him to restore workplace harmony was a valid “exigency of service”.1

Invalid Exigency: SV Singh v UOI

In contrast, Justice Umesh Chandra Banerjee criticized a decision to transfer only one of two officers who were constantly at odds with each other. The administration argued it was necessary to separate them. However, the court observed that removing one person while allowing the other to continue at the same station is not a fair solution and implies a bias. It cannot be termed a valid administrative action if it arbitrarily penalizes one party to a conflict while favoring the other.1

Part V: Grounds for Invalidating a Transfer Order

While courts are deferential to the executive, they have established a “negative list” of scenarios where a transfer order is considered illegal. A detailed analysis of case law reveals the following distinct grounds for invalidation.

5.1 Acting at the Instance of an Incompetent Authority (Political Interference)

The competent authority (e.g., the Department Head) must apply their own mind to the necessity of a transfer. They cannot abdicate this function by acting blindly at the behest of an external party, such as a politician.

- Achyutananda Behera v State of Orissa: In this case, a transfer order was made at the “prodding of the legislator.” The court struck it down, holding that the administrator had failed to apply his own mind. While a representative can bring a grievance to the notice of the administration, the final decision must be an independent administrative one. If the files reveal that the officer merely signed an order dictated by a politician, it is an abdication of statutory duty and thus invalid.1

5.2 Punitive and Stigmatic Transfer

Transfer cannot be used as a cloak for punishment. The disciplinary rules prescribe specific procedures (inquiry, charge sheet) for punishing misconduct. Using transfer to bypass these protections is illegal.

- Merrick v Nott-Bower: Lord Denning observed that the range of punishments does not include transfer.

- Syndicate Bank Ltd. v Workmen / State of UP v Jagdeo Singh: The Supreme Court applied this principle, holding that if an employee is suspected of misconduct, the proper course is to initiate disciplinary proceedings. Transferring them as a “punishment” creates a stigma without due process and is therefore a colorable exercise of power.1

5.3 Transfer to Accommodate Another Person

It is well-settled that transferring one employee simply to make way for another is a mala fide exercise of power. Public interest cannot be sacrificed for private convenience.

- Seshrao Nagorao Umap v State of Maharashtra: The Bombay High Court dealt with a case where an exemplary medical officer was transferred solely to accommodate another doctor who wanted a posting near his private nursing home. The court quashed the order, stating that the power of transfer is not a tool to distribute favors to privileged individuals.1

5.4 Transfer by an Incompetent Authority

This is a jurisdictional error. An order must be issued by the authority legally empowered to do so under the service rules. An order made by an unauthorized officer (e.g., a subordinate who has not been delegated the power) is void from the outset (void ab initio).1

5.5 Transfer Outside Cadre

As explained in Prem Parveen v UOI, transferring an employee to a different service cadre is generally impermissible without consent. Such a transfer can be highly prejudicial, as seniority is often cadre-specific. Moving an employee to a new cadre might force them to join at the bottom of the seniority list, destroying their promotional prospects. Thus, unless there is a specific provision for “inter-cadre transfer” (which usually requires high-level approval and consent), such orders are illegal.1

5.6 Breach of Statutory Provisions

It is an axiomatic rule that a transfer made in violation of a mandatory statutory provision or rule is illegal. The Supreme Court confirmed this in Rajendra Roy v UOI. While administrative “guidelines” are often flexible, statutory “rules” framed under Article 309 of the Constitution are binding.1

Part VI: Impact of Transfer on Employee Status, Seniority, and Personal Life

A fundamental principle governing transfers is that a valid order should not fundamentally alter or prejudice an employee’s status, seniority, or other core conditions of service without a clear legal basis. A transfer is a change of location, not a change of status.

6.1 Protection of Status

A transfer must not result in the extinguishment of an employee’s status as a civil servant.

- The State of Mysore v H Papanna Gowda: The Supreme Court held that transferring a government servant to a “body corporate,” such as a university, was invalid without consent. A university is a distinct legal entity from the government. Transferring a civil servant there effectively terminated their status as a government employee, which amounted to “removal from a civil post” in contravention of the protections under Article 311 of the Constitution.1

6.2 The Doctrine of Equivalence

An employee must be transferred to an equivalent post. But how is equivalence defined?

- Vice Chancellor Lalit Narain Mithila University v Dayanand Jha: The Supreme Court clarified that equivalence is not determined merely by the pay scale. The true criterion is the “status, nature, and responsibility” of the duties attached to the post.

- The Case Facts: A college Principal was transferred to the post of a Reader. The university argued that the pay scales were identical.

- The Judgment: The Court set aside the order. It noted that the post of Principal carried significantly higher administrative duties, responsibilities, and statutory rights (e.g., sitting on the University Senate). To move a Principal to a Reader’s post was a degradation of status, even if the salary remained the same. It was, in effect, a demotion disguised as a transfer.1

6.3 Impact on Seniority

The effect of a transfer on seniority is a complex issue governed by specific rules:

- Transfer in Public Interest: The general rule is that when an employee is transferred in the public interest to a similar post within the same cadre, the transfer does not wipe out their prior length of service. The service rendered in the previous station must be counted for computing seniority in the new post.1

- Transfer at Employee’s Own Request: The rule changes drastically when a transfer is made at the employee’s own request (e.g., to be with a spouse or near a hometown). In such cases, the employee typically forfeits their past service for the purpose of seniority and is placed at the bottom of the seniority list in the new cadre/region. This is the “price” the employee pays for the personal benefit of the transfer.1

6.4 Relevance of Personal Hardship

Courts acknowledge that transfers can cause significant personal hardship—disruption of children’s education, difficulties for working spouses, or care for elderly parents. However, the prevailing judicial opinion is that hardship alone is not a sufficient ground to strike down a transfer order.

- Rajendra Roy v UOI: In this case, the Supreme Court held that it is for the administration, not the court, to weigh the personal hardship of the employee against the administrative needs of the department.

- The Role of Representation: However, courts often refrain from quashing the order but direct the employee to make a “representation” to the competent authority regarding their hardship. This implies an expectation that the administration will act as a “model employer” and consider these factors reasonably. Common hardships, such as the disruption of children’s education during a mid-academic term, are expected to be given due weight by the authorities.1

Part VII: Judicial Review of Transfer Orders

There is a common perception that courts have very limited power to interfere with transfer orders. While it is true that courts are generally reluctant to intervene in what is considered a managerial function, judicial review is available on specific and judicially manageable grounds.

7.1 The Scope of Review

The court’s role is not to act as an appellate authority over administrative decisions. It cannot sit in judgment over whether Officer A is better suited for Station X than Officer B. That is the prerogative of the executive. The court’s role is limited to ensuring that the power to transfer is exercised lawfully.1

As Justice Khalid powerfully observed in P Pushpakaran v The Chairman, Coir Board, when alerted to a potential injustice, the court can and should “tear the veil of deceptive innocuousness” of a transfer order to find the real motive behind it. An order may look innocent on paper (citing “administrative exigency”), but if the facts reveal it was punitive, the court will intervene.1

7.2 Guidelines for Judicial Intervention

The Calcutta High Court, in Bank of India Staff Union v Bank of India, provided a useful analytical summary of the prevailing principles governing judicial review:

- Foundational Principle of Non-Interference: The starting point is that transfer is an incident of service. The decision of who should be transferred and where is a matter for the appropriate authority. Consequently, a court will not interfere unless the order is vitiated by mala fides or violation of statutory rules.

- High Evidentiary Burden: Allegations of mala fides must be proven with a high degree of certainty. A claim of malice in fact requires a “firm foundation of facts” and cannot be sustained on the basis of mere insinuation.

- Absence of Judicially Manageable Standards: Courts recognize their lack of expertise in personnel management. The assessment of suitability involves “imponderables” and subjective opinions. There are no “judicially manageable standards” for a judge to scrutinize the administrative wisdom of a transfer.

- Review Limited to Infraction of Norms: Judicial scrutiny is limited to determining if the decision constituted an infraction of a “professed norm or principle” (e.g., a statutory rule) or was driven by malice.

- Preservation of Service Conditions: A key consideration is whether the transfer adversely affects the employee’s career prospects (status, rank, seniority). If these remain unaffected, judicial interference must be eschewed.1

7.3 Procedural Expectations and Locus Standi

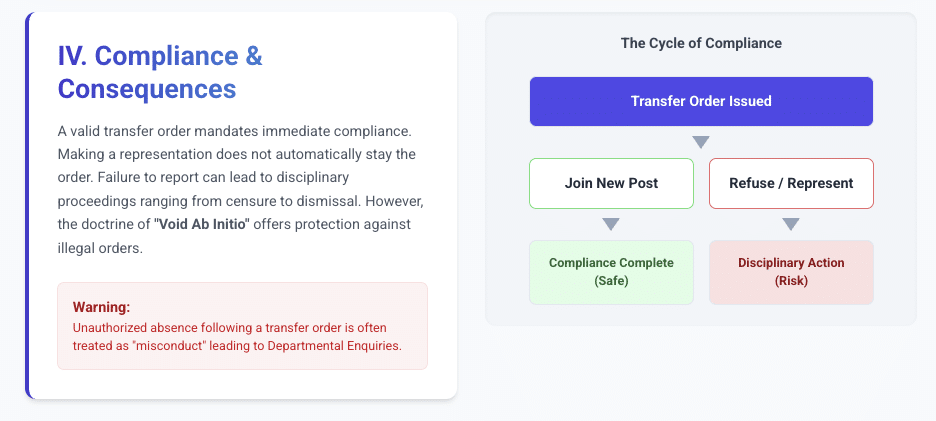

- Report First, Grieve Later: In SC Saxena v UOI, the Supreme Court noted that a government servant should first comply with the transfer order by reporting to their new post and then ventilate their grievances. It is their duty to first report for work.

- Locus Standi: A legal challenge must be brought by the proper party. In K Ashok Reddy v Govt of India, the court established that generally, only the transferred employee themselves has the right to challenge the transfer order. Third parties or unions usually do not have standing to challenge an individual transfer unless it raises broader policy questions.1

Part VIII: Compliance and Consequences of Non-Compliance

A valid transfer order is a lawful directive from the employer, and compliance is mandatory. A public servant cannot refuse to obey an order simply because they find it inconvenient or have submitted a representation against it.

8.1 The Duty to Comply

- Gujarat Electricity Board v Atmaram Sungomal Posbani: The Supreme Court stated unequivocally that a public servant must comply with a transfer order unless it is stayed, modified, or cancelled by a competent authority. The act of making a representation does not automatically operate as a stay on the order. The employee cannot unilaterally decide to wait for a reply before moving.1

8.2 Consequences of Non-Compliance

Failure to comply can have severe repercussions:

- Disciplinary Action: An employee who does not report to their new posting exposes themselves to disciplinary action for “disobedience of lawful orders.”

- Unauthorized Absence: Continued failure to join can be treated as unauthorized absence, which breaks the continuity of service and can lead to dismissal or removal from service.

8.3 The “Void Order” Defense

There is, however, a critical counterpoint. An employee can successfully resist penal consequences if the transfer order itself is proven to be illegal and void.

- Ramesh Chandra Tyagi v UOI: The Supreme Court held that if an initial transfer order is invalid (e.g., passed by an incompetent authority), then a subsequent dismissal for non-compliance with that order will also be illegal. One cannot be punished for disobeying a void order. However, this is a risky strategy for an employee, as the burden of proving the order was void rests on them.1

Part IX: Tabular Chart of Case Laws

The following table serves as a comprehensive reference guide to the key case laws discussed in this report, categorizing them by the type of legal matter they address.

Table 2: Case Laws Related to Transfer and Disciplinary Matters

| Case Name | Court | Legal Matter / Principle Established |

| B Varadha Rao v State of Karnataka | Supreme Court | Incident of Service: Transfer is an implicit condition of service; no vested right to a post. |

| UM Anigol v State of Mysore | Mysore High Court | Definition of Transfer: Must involve movement outside the “Headquarters.” |

| Jawaharlal Nehru University v KS Jawalkar | Supreme Court | Transfer vs. Deputation: Consent is mandatory for transfer to a different employer. |

| Seshrao Nagorao Umap v State of Maharashtra | Bombay High Court | Mala Fides: Transfer to accommodate a favorite (private interest) is illegal. |

| State of Punjab v Gurdial Singh | Supreme Court | Malice in Law: Using power for a purpose other than intended is a fraud on power. |

| TSR Subramanian v UOI | Supreme Court | Public Interest: Political/Arbitrary transfers are deleterious to good governance. |

| Achyutananda Behera v State of Orissa | Supreme Court | Political Interference: Transfer at the “prodding of a legislator” is invalid (abdication of mind). |

| Merrick v Nott-Bower | English Court | Punitive Transfer: Transfer cannot be used as a punishment without inquiry. |

| Syndicate Bank Ltd. v Workmen | Supreme Court | Disciplinary Proceedings: Misconduct must be addressed via inquiry, not transfer. |

| Prem Behari Lal Saxena Case | High Court | Specific Post: Recruitment to a specific isolated post negates liability to transfer. |

| Vice Chancellor LNMU v Dayanand Jha | Supreme Court | Equivalence: Status and responsibility determine equivalence, not just pay scale. |

| State of Mysore v H Papanna Gowda | Supreme Court | Status Protection: Transfer to a corporate body extinguishes civil servant status and is invalid. |

| Rajendra Roy v UOI | Supreme Court | Hardship: Personal hardship is for the administration to consider, not the courts. |

| Gujarat Electricity Board v Atmaram | Supreme Court | Compliance: Must obey transfer order unless stayed; representation is not a stay. |

| Bank of India Staff Union v Bank of India | Calcutta High Court | Judicial Review: Guidelines for court interference (limited to mala fides/statutory breach). |

| Dr. Ramesh Chandra Tyagi v UOI | Supreme Court | Void Order: Punishment for disobeying a void transfer order is illegal. |

| SC Saxena v UOI | Supreme Court | Procedure: “Report first, grieve later.” |

Conclusion

The law of transfer in public service is a dynamic interplay between administrative necessity and individual rights. While the courts have firmly established that the government must have the freedom to deploy its workforce to maximize public efficiency, they have acted as vigilant guardians against the abuse of this power.

The synthesis of case law reveals a clear judicial philosophy:

- Power is Inherent but Conditional: The power to transfer is an incident of service, but it must be exercised bona fide and in the public interest.

- Protection against Malice: The courts will pierce the veil of administrative orders to strike down transfers that are punitive, politically motivated, or driven by personal vendettas.

- Sanctity of Status: While an employee cannot cling to a location, they can cling to their status and rank. Any transfer that degrades these is legally unsustainable.

For the public servant, the law offers protection against arbitrariness but demands obedience to lawful orders. For the administrator, the law offers the flexibility to manage, provided the management is fair, reasoned, and devoid of extraneous influences.

Legal Representation for Service Matters

Navigating the complexities of service law, particularly in matters of transfer and disciplinary proceedings, requires specialized legal expertise. Patra’s Law Chambers provides dedicated legal representation for Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) matters, ensuring that the rights of public servants are vigorously defended against arbitrary administrative actions.

Contact Information:

Patra’s Law Chambers

- Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001

- Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

- Website: patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044