- Disability pension comprises a service element and a disability element, granted if disability ≥20% and linked to service.

- Service connection requires either attributable to or aggravated by military service per GMO‑2023.

- Medical Boards (IMB, RMB, RAMB, AMB, etc.) follow a multi‑stage adjudication pathway to determine entitlement and percentage.

- Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSA) must apply law to reasoned Medical Board findings; unreasoned opinions are legally unsustainable.

- GMO‑2023 provides objective clinical criteria linking conditions (e.g., hypertension, CAD, psychiatric disorders) to specific service exposures.

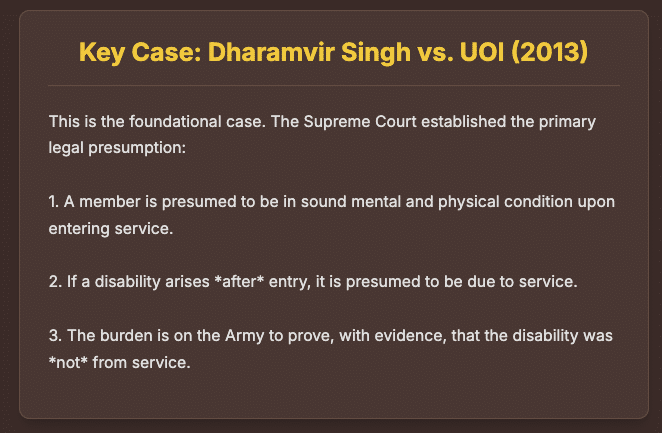

- Supreme Court precedents (eg. Dharamvir Singh, Rajbir Singh) establish presumption of sound health at entry and place onus on the employer.

- Rejected claims can be challenged at the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT); expert military service lawyers significantly improve success prospects.

Securing Your Rights: The Definitive Guide to Disability Pension for Indian Army Personnel

-

Creditor and contributor of this article:

Patra’s Law Chambers:

About Us:

Patra’s Law Chambers is a law firm with offices in Kolkata & Delhi, offering comprehensive legal services across various domains. Established in 2020 by Advocate Sudip Patra (Advocate, Supreme Court of India & Calcutta High Court) an alumnus of the Prestigious Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, IIT Kharagpur ,with Post Graduate diploma in Business Law from IIM Calcutta, the firm specializes in Civil, Criminal, Writs,High Court Matters, Trademark, Copyright, Company, Tax, Banking, Property disputes, Service law, Family law, and Supreme Court matters.You can know more about us in here

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid

Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +91 890 222 4444/ +91 7003 715 325

An Unbreakable Covenant: Understanding the Right to Disability Pension

A. Introduction: The Nation’s Duty to Its Defenders

The service of a soldier is a unique and profound commitment, a willingness to sacrifice one’s all for the nation. As President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address famously implored, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask for what you can do for your country”.1 The personnel of the Indian Armed Forces embody this ethos daily. While citizens enjoy the comforts of civilian life, these soldiers brave harsh, inhospitable conditions at the frontiers, prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice at a moment’s notice.1

The very nature of this service—the immense physical, mental, and spiritual stresses—takes a toll. The human body is not impervious to the daunting conditions of military life, and the possibility of disease and disability comes as a “package deal with the desire, and determination, to serve the country”.1 When a soldier is rendered unable to continue service due to a bodily ailment, the nation has a solemn duty to provide comfort and solace for the remainder of their years. This is not charity; it is a recompense for selfless service.1

This principle is the philosophical bedrock of the disability pension. However, the path to securing this right is often fraught with administrative and legal challenges. The executive branch, tasked with implementing pension regulations, has frequently adopted a restrictive interpretation, leading to a high volume of litigation. This is evidenced by the Supreme Court’s observation in UOI v. Ex Hav. Attar Singh, where it admonished the government for dragging service members to court over granted pensions and called for a more “benevolent approach”.1 Consequently, the judiciary, particularly the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) and higher courts, has emerged as the ultimate guardian of soldier welfare. The courts consistently interpret pension rules as beneficial provisions designed to fulfill a national duty, intervening to ensure the spirit of the law is upheld against overly rigid administrative interpretations. This guide serves to illuminate the path for service members, clarifying their rights and the procedures to secure them, fortified by the very legal precedents that protect them.

B. What is a Disability Pension? Deconstructing Its Components

A disability pension is a financial benefit granted to armed forces personnel who are invalided out of service or are discharged in a low medical category on account of a disability that is connected to their military service. It is not a single payment but is composed of two distinct parts:

- Service Element: This component is calculated based on the qualifying years of service rendered by the individual. It compensates for the service tenure.

- Disability Element: This component is specifically for the disability itself. It is calculated based on the percentage of disability assessed by a Medical Board and is intended to compensate for the loss of earning capacity and the physical and mental hardship caused by the condition.

The primary condition for the grant of a disability pension, as laid out in Regulation 173 of the Pension Regulations for the Army, 1961, is that an individual must be invalided out of service with a disability assessed at 20% or more, which is either “attributable to” or “aggravated by” military service.1

C. The Two Pillars of Entitlement: “Attributable to” vs. “Aggravated by” Military Service

The entire framework of disability pension rests on establishing a service connection. The “Guide to Medical Officers (Military Pensions) – 2023” (GMO-2023) provides the official definitions for the two types of service connection.1

- Attributable to Military Service: This is the most direct form of service connection. It applies when a disease or injury is determined to have been directly and solely caused by the specific conditions of military service. For this to be conceded, a clear and evidence-based “Causal Connection” between the military service and the onset of the condition must be established. For instance, an injury sustained during a training exercise or an infectious disease contracted in a field area would typically be considered attributable.1

- Aggravated by Military Service: This applies to situations where a disease was not caused by service but was either pre-existing at the time of enrolment (even if undetected) or arose during service from non-service-related factors. If evidence indicates that the specific conditions of military service—such as stress, strain, climate, or physical exertion—hastened the onset of the disease or worsened its subsequent course, it is considered aggravated by service. Natural deterioration of a condition, without acceleration by military service, does not qualify as aggravation.1

Establishing this service connection is the most critical step in the pension claim process. It requires a thorough evaluation of medical records, service history, and the application of both medical and legal principles.

The Procedural Roadmap: From Medical Evaluation to Pension Sanction

A. The Medical Adjudication Pathway

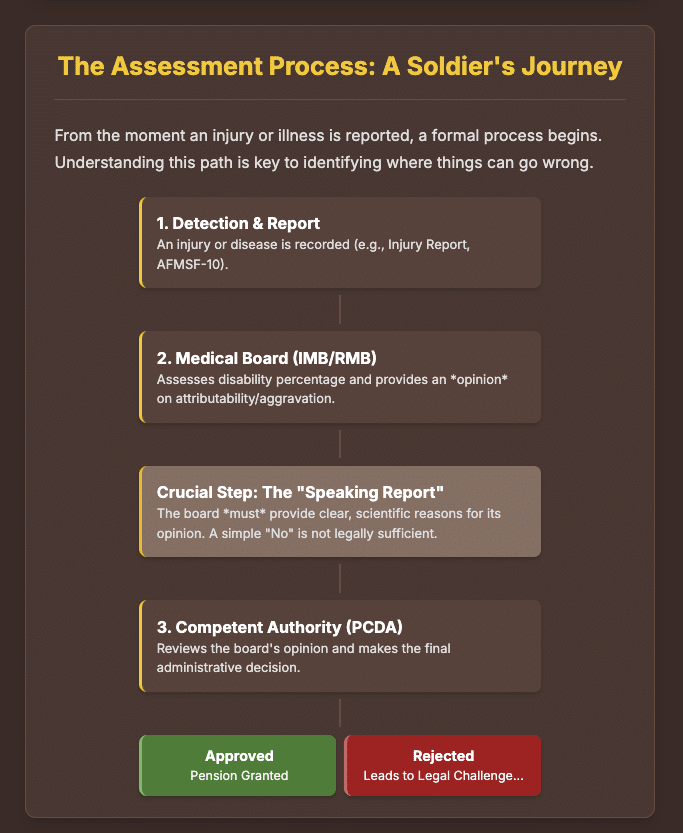

The determination of a soldier’s medical fitness and entitlement to disability pension is a structured, multi-stage process governed by a series of specialized Medical Boards. Each board has a distinct function, and understanding this sequence is crucial for any service member navigating the system. The GMO-2023 outlines this procedural pathway, which is summarized below.1

Table 1: The Medical Board Adjudication Pathway

| Board Type | Form No. | Primary Function & Significance |

| Classification Medical Board | AFMSF-15 | Conducts the initial temporary downgrading of a soldier’s medical category for conditions requiring extended convalescence. It makes the first crucial endorsement on entitlement (Attributable/Aggravated/NANA). |

| Reclassification Medical Board | AFMSF-15 | Reviews a soldier’s temporary low medical category status to decide whether to upgrade, downgrade, or maintain it. It does not comment on entitlement. |

| Invalidment Medical Board (IMB) | AFMSF-16 | Convened when a service member is to be invalided out of service on medical grounds before completing their term. It makes a definitive pronouncement on both entitlement and the percentage of disability. |

| Release Medical Board (RMB) | AFMSF-16 | Conducted for all personnel who are retiring or being discharged while in a Low Medical Category (LMC). It determines their final eligibility for impairment compensation, commenting on both entitlement and assessment. |

| Retention Cum Impairment Assessment Board (RIAB) | AFMSF-15 | A pivotal board for personnel placed in a permanent LMC (‘For Life’). It decides whether the individual can be retained in a sheltered appointment or must be invalided out, and can award impairment relief. |

| Re-Assessment Medical Board (RAMB) | AFMSF-17 | Conducted post-discharge for veterans whose impairments were not considered permanent at the time of the RMB. It comments only on the assessment percentage, which is then finalized for life. |

| Appeal Medical Boards (AMBs) | AFMSF-16 | Sanctioned by the office of the DGAFMS upon a service member’s appeal against the findings of an RMB or IMB. This board has the authority to change both the entitlement and the assessment percentage. |

| Review Medical Board (Rev MB) | AFMSF-17 | A one-time final review for veterans who believe their attributable impairment has worsened or was incorrectly assessed by the RMB. It can only change the assessment percentage, not the entitlement. |

| Post Discharge Medical Board (PDMB) | AFMSF-16 | A provision for veterans who were in the highest medical category (SHAPE-I) at retirement but develop an attributable disability within 7 years of discharge. |

This pathway shows that the medical evaluation is a dynamic process with several checks and opportunities for review. However, the initial findings of the IMB or RMB are critical, as they form the basis for the subsequent pension claim.

B. The Final Decision: The Role of the Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSA)

#image_title

After the final Medical Board (typically the RMB or IMB) submits its proceedings, the case is forwarded to the Pension Sanctioning Authority (PSA), such as the Principal Controller of Defence Accounts (Pensions).1 The PSA is the executive body that makes the final decision to grant or reject the disability pension claim.1

Crucially, the PSA’s role is not merely to rubber-stamp the Medical Board’s opinion. As established in a plethora of Supreme Court judgments, the PSA is bound by the principles of law. It cannot mechanically reject a claim based on a Medical Board’s opinion if that opinion is unreasoned or contradicts the established legal presumptions. The PSA must consider all evidence and apply the law correctly, failing which its decision is liable to be challenged before the Armed Forces Tribunal.1

Clinical Guidelines for Common Service-Related Disabilities

A. How Medical Boards Determine Service Connection: The GMO-2023 Framework

The GMO-2023 mandates an evidence-based approach for Medical Boards when determining service connection. It explicitly states that a “bare medical opinion without reasons in support will be of no value to the Competent/Appellate Authorities”.1 This underscores the legal requirement for a reasoned decision.

The board must critically examine all available evidence, including 1:

- Injury Reports and Courts of Inquiry (CoI): Primary documents for establishing the circumstances of an injury.

- Medical Documents: The complete medical history of the service member, including initial records (AFMSF-15) and final board proceedings (AFMSF-16).

- Specialist Opinions: Detailed reports from medical specialists on the etiology and progression of the disease.

- Service History: Records of postings to field areas, high-altitude areas (HAA), or involvement in operations, which can serve as evidence of exposure to stress and strain.

B. In-depth Analysis of Specific Conditions

For years, the argument of “stress and strain of military service” was often subjective. The GMO-2023 marks a significant shift by codifying specific, objective criteria that link certain common diseases to military service conditions. This transforms the debate from a general claim about stress to a specific, evidence-based argument about whether a soldier’s service history meets these official criteria. For many so-called “lifestyle diseases,” the guide now provides clear exceptions where attributability or aggravation can be conceded.1 A soldier who is told their hypertension is simply a lifestyle issue can now point to a specific rule that links it to HAA service, fundamentally strengthening their claim.

Table 2: Clinical Criteria for Attributability/Aggravation Under GMO-2023

| Condition | General Rule (Typically Not Attributable) | Key Exceptions for Attributability/Aggravation |

| Hypertension (Primary) | Considered a multifactorial lifestyle and genetic disease. | Attributability is conceded if the onset occurs while serving in a High-Altitude Area (HAA) for at least three continuous months or within three months of de-induction from such an area.1 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | Considered a multifactorial lifestyle and genetic disease. | Attributability is conceded only if an Acute Coronary Syndrome or Sudden Cardiac Death occurs during or in close proximity to specific service conditions: service in HAA, on ships/submarines, during active operations, or within 72 hours of heavy physical exertion ($>7$ METS) for service requirements.1 |

| Psychiatric Disorders | Result from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. | Attributability is conceded when the disorder arises during service in a combat zone, active counter-insurgency area, HAA (min. 3 months continuous tenure), extremely isolated posts, or during involvement in catastrophic disaster relief. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) under these conditions is specifically noted as attributable. Psychoactive substance/alcohol abuse is explicitly excluded.1 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | Generally not considered attributable or aggravated due to its strong genetic and lifestyle links. | Attributability may be considered only in rare cases of pancreatogenic diabetes where there is unequivocal evidence that it was caused by a service-related trauma or infection that damaged the pancreas.1 |

| Neck Pain & Back Ache (incl. PIVD) | Primarily considered degenerative in nature. | Attributability is conceded only if an established causal and temporal relationship with a specific injury sustained due to military service is proven through evidence.1 |

| Epilepsy/Seizures | Often considered a constitutional or idiopathic disease that may escape detection at enrolment. | Attributability is conceded only if the cause is established to be a direct result of a service-related trauma (e.g., head injury) or infection (e.g., meningitis, cysticercosis).1 |

| Stroke (Cerebrovascular Accident) | Often linked to non-service factors like hypertension or atherosclerosis. | Attributability is appropriate if there is sufficient evidence of an underlying service-related cause, such as an infection, service-related trauma, or precipitation by the hypercoagulable state induced by HAA service.1 |

The Legal Bedrock: Landmark Judgments That Protect Your Rights

A. The Power of Precedent: How Courts Shape Pension Law

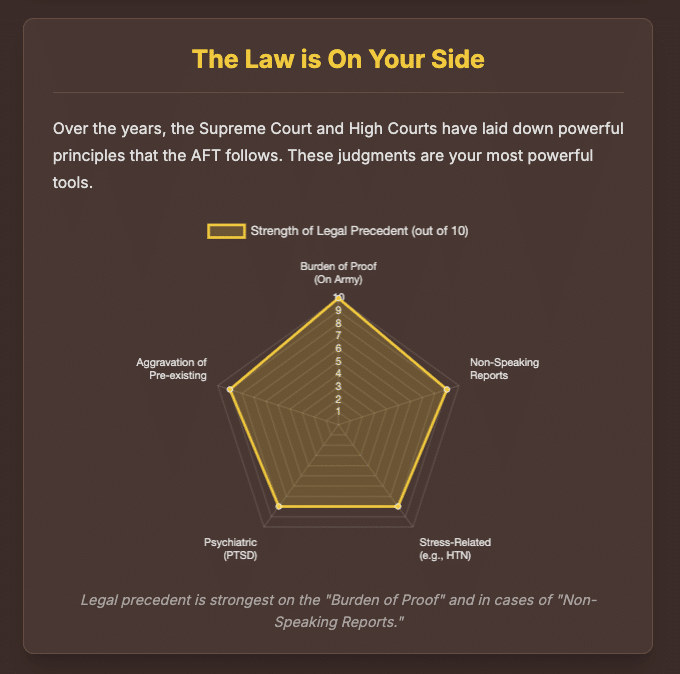

The interpretation of pension regulations is not static; it is a dynamic area of law continuously shaped by landmark judgments from the Supreme Court and various High Courts. These judicial precedents are not mere suggestions; they are binding on all lower authorities, including Medical Boards, the Pension Sanctioning Authority, and the Armed Forces Tribunal. They establish the correct legal framework for interpreting the rules and ensure that the rights of service personnel are protected.

B. Foundational Legal Principles Established by the Supreme Court

Through a series of landmark rulings, the Supreme Court has laid down several foundational principles that form the bedrock of disability pension jurisprudence. These principles are consistently cited by the AFT and High Courts to grant relief to soldiers whose claims have been wrongfully rejected.1

- Presumption of Sound Health at Entry: This is perhaps the most critical principle. If a soldier is found medically fit at the time of enrolment, with no disability or disease noted in their service record, the law presumes them to have been in a sound physical and mental condition. If they are subsequently discharged on medical grounds, any deterioration in their health is presumed to be due to military service. This principle was firmly established in Dharamvir Singh v. UOI and has been consistently followed.1

- The Onus of Proof is on the Employer: Stemming from the first principle, the burden of proof does not lie with the soldier to prove that their disability is service-connected. Instead, the onus is heavily on the military establishment to produce evidence to rebut the presumption of service connection. The claimant is not required to prove the conditions of entitlement and must be given the benefit of any reasonable doubt. This was a key finding in both Dharamvir Singh v. UOI and UOI v. Rajbir Singh.1

- The Mandate for a Reasoned Medical Opinion: The courts have repeatedly held that a Medical Board cannot simply state a conclusion, such as “Neither Attributable to Nor Aggravated by service (NANA),” without providing detailed, cogent, and scientific reasons for that conclusion. An opinion devoid of reasoning, especially when it seeks to overturn the legal presumption of service connection, is considered a product of non-application of mind and is legally unsustainable. A decision by the PSA based on such an unreasoned opinion is arbitrary and liable to be set aside.1

- Beneficial and Liberal Interpretation: The Supreme Court has consistently held that pension regulations are a form of beneficial or welfare legislation. Therefore, they must be interpreted liberally and in a manner that advances their purpose, which is to provide succour to disabled soldiers. A narrow or hyper-technical interpretation that defeats the object of the rules is impermissible.8

C. Comprehensive Table of Landmark Judgments

The following table compiles key judgments from the Supreme Court and Tribunals that have shaped the landscape of disability pension law in India. These precedents are invaluable tools for any service member seeking to understand and assert their rights.

Table 3: Landmark Judgments on Disability Pension

| Case Name & Citation | Court | Key Principle / Ruling |

| Dharamvir Singh v. UOI (2013) 7 SCC 316 | Supreme Court | Establishes foundational principles: 1) Presumption of sound health at entry if no disability is noted. 2) Onus of proof is on the employer, not the claimant. 3) A Medical Board’s opinion must be supported by reasons; an unreasoned opinion indicates non-application of mind.1 |

| UOI v. Rajbir Singh (2015) 12 SCC 264 | Supreme Court | Reaffirms Dharamvir Singh. Holds that if a person is discharged on medical grounds, the disability is presumed to have arisen in service and be attributable/aggravated unless the Medical Board provides reasons to rebut this presumption.[1, 1, 4, 5, 6] |

| Sukhvinder Singh v. UOI (2014) 14 SCC 364 | Supreme Court | Any disability not recorded at recruitment must be presumed to be a consequence of military service unless proven otherwise. The benefit of the doubt must be extended to the member.[1, 1, 4] |

| UOI v. Ram Avtar (2014 SCC OnLine SC 1761) | Supreme Court | A key judgment related to the rounding off (or broad-banding) of disability pension percentages (e.g., a disability of 20% to be rounded off to 50% for pension calculation).[1, 1, 12] |

| UOI v. Manjeet Singh (2015) 12 SCC 275 | Supreme Court | Declares that Pension Regulations, Entitlement Rules, and the GMO are statutory in nature and binding. Absence of reasons to support a Medical Board’s opinion that a disability is not attributable/aggravated makes the denial of pension illegal.[1, 1, 6] |

| UOI v. Angad Singh Titaria (2015) 12 SCC 257 | Supreme Court | Simply recording a conclusion that a disability is not attributable to service, without giving reasons, shows a lack of proper application of mind by the Medical Board and cannot be upheld.[1, 1, 13, 14] |

| Ex Gnr Laxmanram Poonia v. UOI (2017) 4 SCC 697 | Supreme Court | An unreasoned opinion of the Medical Board cannot be read in isolation; it must be read in consonance with the Entitlement Rules and GMO. In the absence of contrary evidence, it’s presumed the individual was in sound health at entry.1 |

| Secretary, Govt. of India v. Dharambir Singh (2020) 14 SCC 582 | Supreme Court | For a disability to be attributable, there must be a relevant and reasonable causal connection, “howsoever remote,” between the incident and military service. An act entirely alien to service (e.g., a private errand on leave) does not qualify.1 |

| Ex Cfn Narsingh Yadav v. UOI (2019) 9 SCC 667 | Supreme Court | For certain constitutional/hereditary diseases (like schizophrenia), it cannot be automatically presumed that the condition is attributable to service just because it wasn’t detected at recruitment. The scope for judicial review of a medical board’s opinion is limited unless there is strong counter-evidence.[1, 1, 13, 15, 16] |

| UOI v. R. Munusamy (2022 SCC OnLine SC 892) | Supreme Court | Distinguishes cases where discharge is on administrative grounds (e.g., “undesirable soldier”) from medical invalidment. The presumption of attributability does not apply if the discharge was not on account of the disease.1 |

| UOI v. Ex Hav. Attar Singh (2025 Order in CA 10637/2024) | Supreme Court | Admonishes the Union of India for filing appeals in every disability pension case granted by the AFT and calls for a more benevolent approach and a policy to scrutinize such appeals.1 |

| UOI v. Keshar Singh (2007) 12 SCC 675 | Supreme Court | An earlier judgment emphasizing the primacy of the Medical Board’s opinion, though later judgments like Dharamvir Singh have clarified that this opinion must be reasoned.[1, 1, 17, 18, 19] |

| Veer Pal Singh v. Ministry of Defence (2013) 8 SCC 83 | Supreme Court | While courts are loath to interfere with expert medical opinions, judicial review is not excluded. The opinion deserves “respect, not worship,” and courts can examine the record to see if the conclusion is legally sustainable.[1, 1, 4, 20] |

| UOI v. Jujhar Singh (2011) 7 SCC 735 | Supreme Court | A discharged person can be granted disability pension only if the disability is attributable to or aggravated by military service and such a finding is recorded by Service Medical Authorities.[1, 1, 21, 22] |

| Ministry of Defence v. A.V. Damodaran (2009) 9 SCC 140 | Supreme Court | Emphasized the authority of the Medical Board and the necessity for its findings to be given due weight in disability pension cases.[1, 1, 23, 24, 25] |

| UOI v. Baljit Singh (1996) 11 SCC 315 | Supreme Court | Unless there is clear evidence to negate the Medical Board’s findings, disability pension should not be granted.[1, 1, 17, 18] |

| UOI v. Ram Prakash (2010) 11 SCC 220 | Supreme Court | Cited to support the weight given to Medical Board findings, though later distinguished in cases where the Board’s opinion lacked reasoning.[1, 1, 26, 27] |

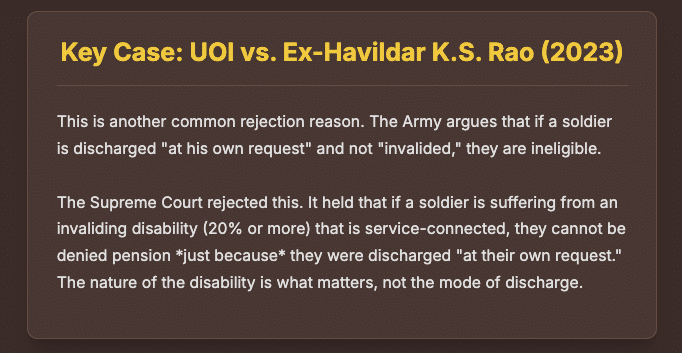

| UOI v. Ajay Wahi (2010) 11 SCC 213 | Supreme Court | An officer who retires voluntarily is not eligible for disability pension under Regulation 50, distinguishing them from those invalided out of service.[28, 29, 30, 31, 32] |

| Madan Singh Shekhawat v. UOI (1999) | Supreme Court | Ruled that rules governing disability pension are beneficial provisions and must be interpreted liberally to give them a wider meaning.[8, 9, 10, 33] |

| K.J.S. Buttar v. UOI (2011) 11 SCC 429 | Supreme Court | Established the principle of rounding off disability percentages (e.g., 50-75% to be treated as 75%) and held that denying these benefits to pre-1996 retirees is discriminatory under Article 14.[34, 35, 36, 37] |

| Bijender Singh v. UOI (2025 INSC 549) | Supreme Court | Reaffirmed that if a disease is not recorded at enrolment, it is presumed to have arisen during service. Held that if a person is invalided out, their disability is assumed to be over 20%.[34, 38] |

| Ex Sgt Girish Kumar v. UOI & Ors (2017 AFT PB) | AFT (Full Bench) | A key judgment from the AFT Principal Bench on the issue of broad-banding/rounding off of the disability element of pension.[12] |

| UOI v. Dhir Singh China (2003) 2 SCC 382 | Supreme Court | Held that the decision of the Medical Board is sacrosanct and judicial review is impermissible, a principle later refined by the “reasoned opinion” doctrine.[13] |

Challenging a Rejection: Your Right to Appeal at the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT)

A. The Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) as a Forum for Justice

When a service member’s claim for disability pension is rejected by the departmental authorities, it is not the end of the road. The Armed Forces Tribunal Act, 2007, established the AFT as a specialized judicial body to provide speedy and effective adjudication of disputes and complaints regarding service matters, including pensions.39 The AFT is composed of a judicial member (a retired High Court Judge) and an administrative member (a senior retired armed forces officer), ensuring that cases are heard with both legal and service-related expertise.1

B. The Process of Filing an Appeal: A Practical Overview

If a claim for disability pension is rejected by the PSA, or if a first appeal to the departmental appellate authority is dismissed, the aggrieved person can seek legal recourse by approaching the AFT.14 The procedure is as follows:

- Filing an Original Application (OA): The case is initiated by filing an “Original Application” under Section 14 of the AFT Act, 2007. This application details the facts of the case, the grounds for the claim, and the relief sought.3

- Submission of Documents: The OA must be accompanied by all relevant documents, including service records, medical board proceedings, the rejection letter from the PSA, and any other evidence supporting the claim.

- Notice to Respondents: Once the Tribunal admits the application, it issues a notice to the respondents, typically the Union of India through the Ministry of Defence and the relevant service headquarters.39

- Pleadings: The respondents file a detailed reply to the application, and the applicant is given an opportunity to file a rejoinder to counter the points made in the reply.39

- Final Hearing: After the pleadings are complete, the case is listed for a final hearing where lawyers for both sides present their arguments based on the facts, regulations, and relevant case law.

- Judgment: The Tribunal delivers a reasoned judgment, which is binding on the parties. If the Tribunal rules in favor of the applicant, it will direct the government to grant the disability pension, often with arrears.39

An order of the AFT can be challenged by filing a writ petition before the jurisdictional High Court or by seeking leave to appeal before the Supreme Court under Section 31 of the AFT Act.14

C. Why Expert Legal Representation is Crucial

The process of challenging a pension rejection at the AFT is a formal legal proceeding. Success hinges on a deep understanding of the complex web of Pension Regulations, the latest Entitlement Rules, the detailed medical guidelines in the GMO-2023, and the vast and ever-evolving body of case law from the Supreme Court and various High Courts.

An expert military service lawyer can:

- Meticulously analyze the service and medical records to build a strong, evidence-based case.

- Identify the specific legal principles and landmark judgments that are most relevant to the facts of the case.

- Effectively argue how the Medical Board’s opinion may be legally flawed, especially if it is unreasoned or contradicts established presumptions.

- Draft precise and persuasive legal documents (OAs and rejoinders) and articulate compelling arguments during the final hearing.

Navigating this specialized area of law without expert guidance can be exceedingly difficult. Professional legal counsel is essential to ensure that a soldier’s rights are effectively and vigorously defended.

Why You Need an Expert

The rules are complex, and the authorities often rely on technicalities to deny claims. The Guide to Medical Officers (GMO) – 2023 itself is a 150+ page technical document.

Navigating this, and challenging a powerful organization, requires deep specialized knowledge of military service law and the precedents set by the AFT and Supreme Court.

Patra’s Law Chambers is a full-service law firm with dedicated expertise in handling military service matters and disability pensions. We have successfully represented numerous officers, JCOs, and soldiers before the Armed Forces Tribunal (AFT) and High Courts, securing the pensions they were rightfully denied.

Don’t let a simple rejection be the final word on your service and sacrifice.

Contact Patra’s Law Chambers Today

Our team of experts is ready to evaluate your case.

Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

#MilitaryLaw #ServiceLaw #DisabilityPension #IndianArmedForces #ArmedForcesTribunal #LegalAnalysis #VeteransAffairs #PatrasLawChambers

Works cited

- Armed Forces Tribunal grants disability pension to former army personnel suffering from primary hypertension – SCC Online, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/12/25/aft-grants-disability-pension-former-army-man-suffering-from-hypertension/

- OA 581-2018.pdf – Armed Forces Tribunal, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.aftdelhi.nic.in/assets/judgement/2024/OA/OA%20581-2018.pdf

- cites: 14087452 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=cites:14087452

- REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO.2904 OF 2011 Union of India & Anr., accessed on October 28, 2025, https://api.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/42379.pdf

- 07.2025 + W.P.(C) 140/2024, CM APPL., accessed on October 28, 2025, https://images.assettype.com/barandbench/2025-07-04/zfwlor6f/Union_Of_India___Ors__Vs_Col__Balbir_Singh__Retd_.pdf

- Discharge of Serviceman or Denial of Disability Pension Based on Unreasoned Medical Board Report Would Be Unsustainable in Law: Supreme Court – SCC Online, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/05/09/discharge-serviceman-denial-disability-pension-unreasoned-medical-board-report-supreme-court/

- Dharam Vir Singh Vs Union of India (UOI) and Others – CourtKutchehry, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.courtkutchehry.com/judgements/273931/dharam-vir-singh-vs-union-of-india-uoi-and-others/

- Madan Singh Shekhawat v. Union Of India And Others | Supreme Court Of India – CaseMine, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5609ad66e4b01497114114b1

- INDIAN LAW REPORT (M.P.) COMMITTEE PATRON CHAIRMAN MEMBERS SECRETARY – Mphc.gov.in, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://mphc.gov.in/ilr/assets/pdf_docs/2020/ILR_October_2020.pdf

- SC Disability Ruling: Liberal View Must Guide Army Pension …, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.deccanherald.com/india/liberal-approach-must-be-adopted-while-considering-disability-pension-to-army-men-sc-3530750

- Disability Pension in Armed Forces : Eligibility & Legal Process – Tanwar Law Associates, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://advocatesstanwar.in/disability-pension-in-armed-forces/

- Guide to Filling cases in the Armed Forces Tribunal( AFT) of India – Patras Law Chamber, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://patraslawchambers.com/guide-to-filling-cases-in-the-armed-forces-tribunal-aft-of-india/

- ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI ORDER A.C.A.Adityan, Member (J): This application is for grant of disability pensi, accessed on October 28, 2025, https://www.aftdelhi.nic.in/benches/kochi_bench/judgments/february2012/OA_30_of_2010.pdf