- ACRs are vital administrative performance appraisals affecting promotion, confirmation, and retention in public service.

- The impact test (Dev Dutt) treats entries by practical effect, not mere phraseology, to determine adversity.

- Adverse remarks must be communicated and the employee given a right of representation before action.

- Uncommunicated adverse entries are generally inadmissible to the employee’s prejudice, with limited contextual exceptions.

- Successful representations lead to expunction; expunged remarks are legally treated as non-existent.

- Courts intervene only for patent illegality, arbitrariness, bias, or procedural violations in ACRs.

- The washing off doctrine is contested: past adverse entries may lose force for service continuation but remain relevant in comparative promotions.

Adverse Confidential Reports(ACR) in Govt. Service

Contributor of the article:

Patra’s Law Chambers:

- Kolkata Office: NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

- Delhi Office: House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

- If you want to get legal consultation regarding any law-related matter in government service please click here.

Introduction

Annual Confidential Reports (ACRs) are a cornerstone of public service administration in India, serving as critical instruments for performance appraisal. Yet, for the individual public servant, they can be a source of profound career anxiety. An adverse remark, whether explicit or implied, can derail promotions, affect confirmations, and cast a long shadow over a meticulously built career. This analysis provides a detailed legal examination of the principles governing these reports, the procedural safeguards available to employees, and the evolving jurisprudence shaped by the Supreme Court of India. We will navigate the complex legal framework that seeks to balance administrative efficiency with the fundamental tenets of fairness and natural justice.

——————————————————————————–

1. The Foundational Principles of Confidential Reports

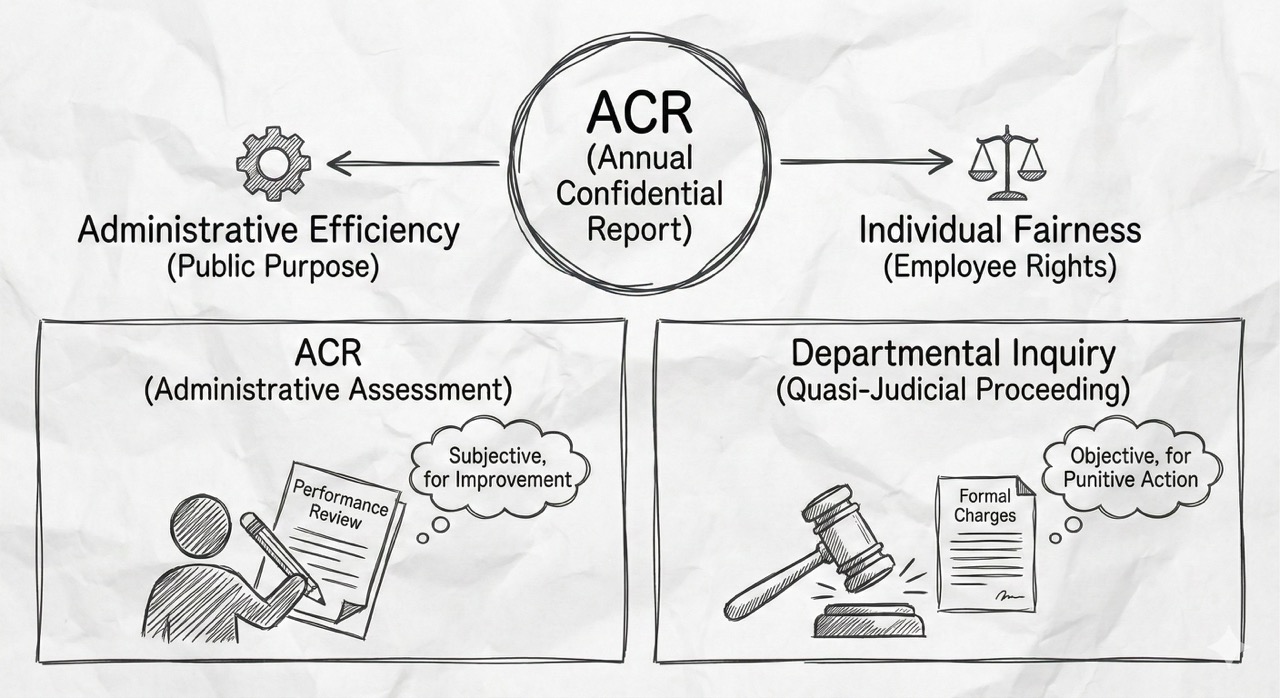

The entire legal framework governing confidential reports is built upon the dual, and sometimes competing, needs of administrative efficiency and individual fairness. The system is designed not merely to judge performance but to serve a larger public purpose. This section deconstructs the fundamental nature, objective, and legal character of these pivotal service records.

Confidential reports are defined as essential performance appraisals that constitute the “basic and vital inputs” for assessing an officer’s career trajectory. The Supreme Court, in Rajendra Singh Verma v Lt Governor (NCT of Delhi), affirmed that these reports are crucial for judging an employee’s suitability for promotion, confirmation, and even retention in service. However, their object is multifaceted. The judiciary has clarified that these reports exist to give an officer an opportunity “to make amends for his remissness, to reform himself,” and ultimately, to improve the efficiency of public service.

It is crucial to distinguish the nature and purpose of an ACR from a formal departmental enquiry. The former is an administrative assessment, while the latter is a quasi-judicial proceeding intended to form the basis for punitive action. This distinction was articulated with precision in Puran Singh v State of Punjab:

An annual confidential report is in essence subjective and administrative whilst a departmental enquiry is inevitably objective and quasi-judicial.

Despite their administrative and subjective nature, the recording of entries in an ACR is not a matter of absolute discretion. The judiciary has consistently mandated that the process must be governed by fairness and objectivity. Synthesizing the observations from Biswanath Prasad Singh v State of Bihar and S Ramchandra Raju v State of Orissa, the Supreme Court has clarified that entries must be the result of an objective assessment of an employee’s work and conduct. The report should not be an instrument to be wielded arbitrarily or become a reflection of “personal whims, fancies or prejudices.”

This insistence on objectivity naturally leads to the critical legal question that triggers a cascade of procedural rights: what exactly constitutes an “adverse remark”?

2. Defining an “Adverse Remark”: The Evolution from Phraseology to Impact

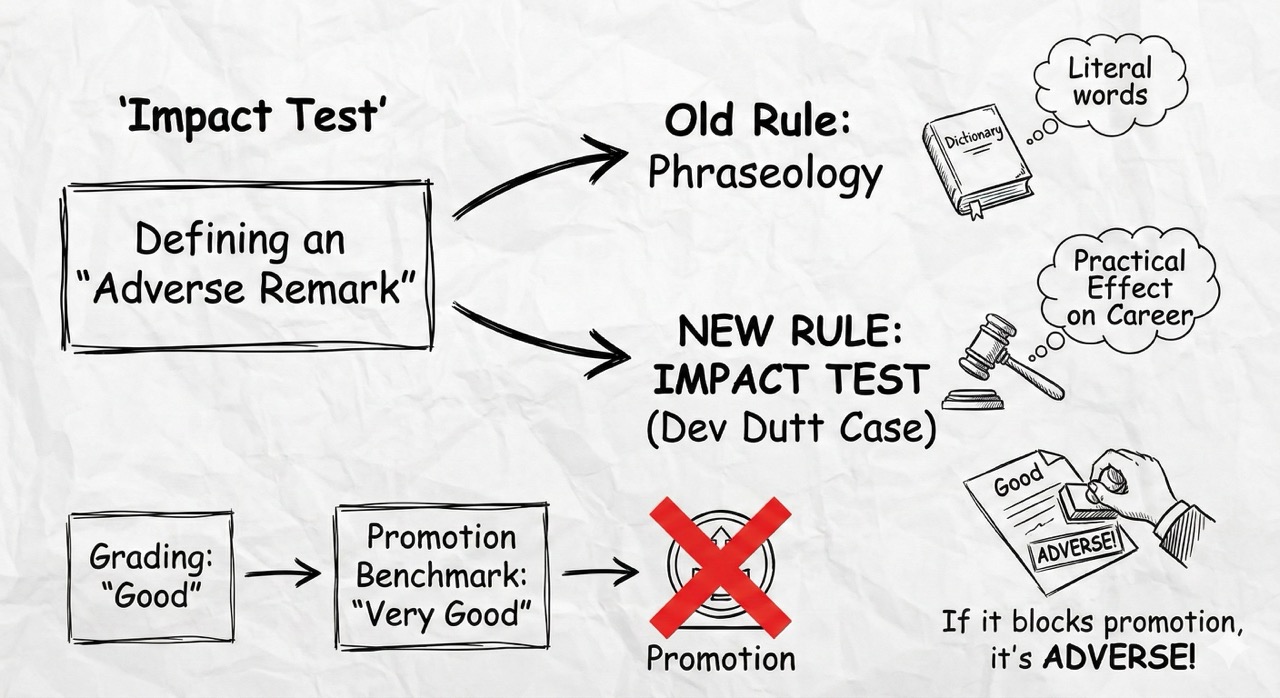

The strategic importance of precisely defining an “adverse remark” cannot be overstated, as this definition triggers significant legal rights and procedural obligations for both the employer and the employee. Recognizing this, the judiciary has moved beyond a literal interpretation of words and phrases to a more substantive test that examines the real-world impact of an entry on an employee’s career prospects.

As a starting point, the All India Services (Confidential Rolls) Rules, 1970, provide a formal definition, stating that an adverse remark is one that indicates “defects or deficiencies in the quality of work or performance or conduct of an officer.” While this definition is instructive, the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence has significantly broadened its scope.

The most significant development in this area is the “impact test” formulated by the Supreme Court in Dev Dutt v UOI. This principle fundamentally shifted the analysis from the phraseology of the remark to its practical consequences. The Court explained that if the benchmark for promotion is a “very good” grading, then an entry of “good” is, in effect, an adverse remark because it eliminates the candidate from consideration. The Court’s reasoning is dispositive:

Thus, nomenclature is not relevant, it is the effect which the entry is having which determines whether it is an adverse entry or not. It is thus the rigours of the entry which is important, not the phraseology.

In such a scenario, the “good” entry has an adverse effect on the employee’s chances of promotion and must be treated as an adverse remark, triggering the right to representation.

The following table, based on established case law, illustrates this nuanced distinction:

| Adverse Remarks | Non-Adverse Remarks |

| A downgrading of an entry from “outstanding” in one year to “satisfactory” in the next (UP Jal Nigam). | A remark that an employee is “not yet fit for confirmation.” |

| An entry of “good” when the promotional benchmark requires “very good” (Dev Dutt). | Remarks suggesting that an employee’s relations with colleagues or the public require improvement. |

| A remark that an officer “is constantly trying to get around his superior, by sweet talk/visits/gifts.” | A remark that there were complaints of drinking against an employee. |

This impact-focused definition logically connects the nature of the remark to the procedural rights that an employee is entitled to upon receiving one.

3. The Pillars of Natural Justice: Communication and the Right of Representation

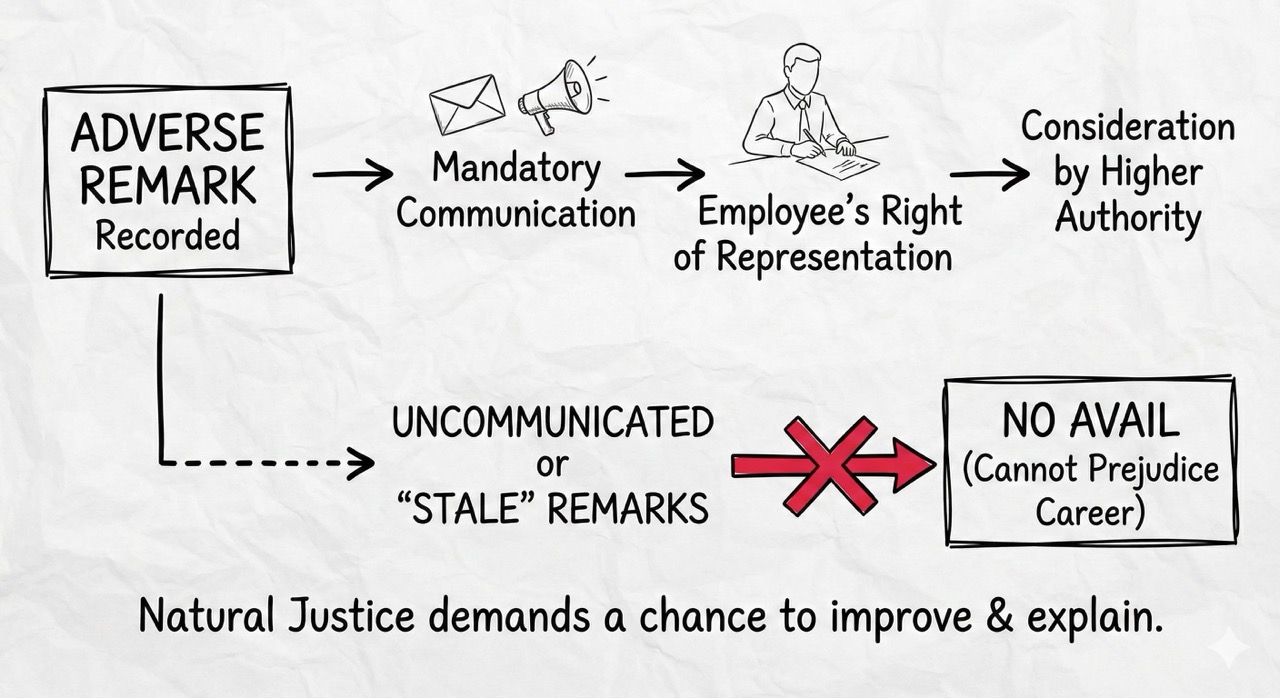

While the recording of an ACR is an administrative function, it is not an executive action exempt from the principles of natural justice. The law, striking a pragmatic balance between administrative necessity and constitutional fairness, does not mandate a prior hearing. Instead, it ensures fairness through robust post-decisional safeguards: the mandatory communication of adverse remarks and the corresponding right of the employee to make a representation against them.

The established legal principle is that a reporting officer is not required to provide an employee with an opportunity to be heard before an adverse remark is recorded. However, to ensure compliance with the principles of natural justice, the law mandates a subsequent opportunity for the employee to present their case.

This brings us to the absolute obligation to communicate adverse remarks. In the leading case of Gurdial Singh Fijji v State of Punjab, Chandrachud, CJ, articulated the seminal principle in clear terms:

The principle is well-settled that in accordance with the rules of natural justice, an adverse report in a confidential roll cannot be acted upon to deny promotional opportunities unless it is communicated to the person concerned so that he has an opportunity to improve his work and conduct or to explain the circumstances leading to the report. Such an opportunity is not an empty formality, its object, partially, being to enable the superior authorities to decide on a consideration of the explanation offered by the person concerned, whether the adverse report is justified.

Following communication, the employee possesses a “valuable right” to make a representation. As affirmed in Dev Dutt v UOI, it is not “just and fair” for an employer to act upon such a remark before the representation is considered and disposed of by an authority higher than the one who made the entry. This ensures an independent review and upholds the integrity of the appraisal process.

This crucial procedural safeguard begs the question: what are the legal consequences if this vital step of communication is overlooked or unduly delayed?

4. The Legal Status of Uncommunicated Adverse Remarks

The legal status of uncommunicated adverse remarks is one of the most significant areas in service law, with its interpretation depending heavily on the purpose for which the remark is being used. The potential for profound prejudice to an employee’s career has led to a clear general rule, albeit one with nuanced exceptions.

The general rule, firmly established in Gurdial Singh Fijji, is that uncommunicated adverse remarks are of “no avail and cannot be relied upon for any purpose to the prejudice of the petitioner.” Such remarks are not considered relevant material and cannot form the basis for prejudicial administrative decisions like the denial of promotion.

However, a review of judicial precedents reveals an apparent conflict. While Fijji’s case is clear, observations in cases like UOI v ME Reddy and RL Butail v UOI have been interpreted to suggest that uncommunicated remarks can sometimes be considered. A closer analysis reconciles these decisions. The Reddy and Butail line of cases often involved specific contexts that distinguish them from the general rule:

- Non-punitive Actions: These cases frequently dealt with actions like compulsory retirement, which is not considered a punishment. The standard of review is different, and the primary consideration is public interest, not penalizing the employee.

- Totality of the Service Record: The decisions were often based on an assessment of the entirety of the service record, where the uncommunicated remark was not the sole or primary basis for the action but part of a larger pattern of performance.

Therefore, the core principle remains that for actions that are clearly prejudicial to an employee’s career advancement, such as promotion, uncommunicated remarks cannot be the deciding factor.

Furthermore, the law addresses the effect of delayed communication. If adverse remarks are communicated after several years, the very object of communication—to allow the employee to improve—is defeated. In Baidyanath Mahapatra v State of Orissa, the Supreme Court held that such “stale entries” cannot be relied upon to the employee’s prejudice, as belated communication renders it impossible for an employee to make an effective representation.

The consequences of non-communication naturally lead to an examination of the legal remedies available to an aggrieved employee and the role of the judiciary in overseeing this process.

5. Remedies and Judicial Scrutiny: Expunction and Its Aftermath

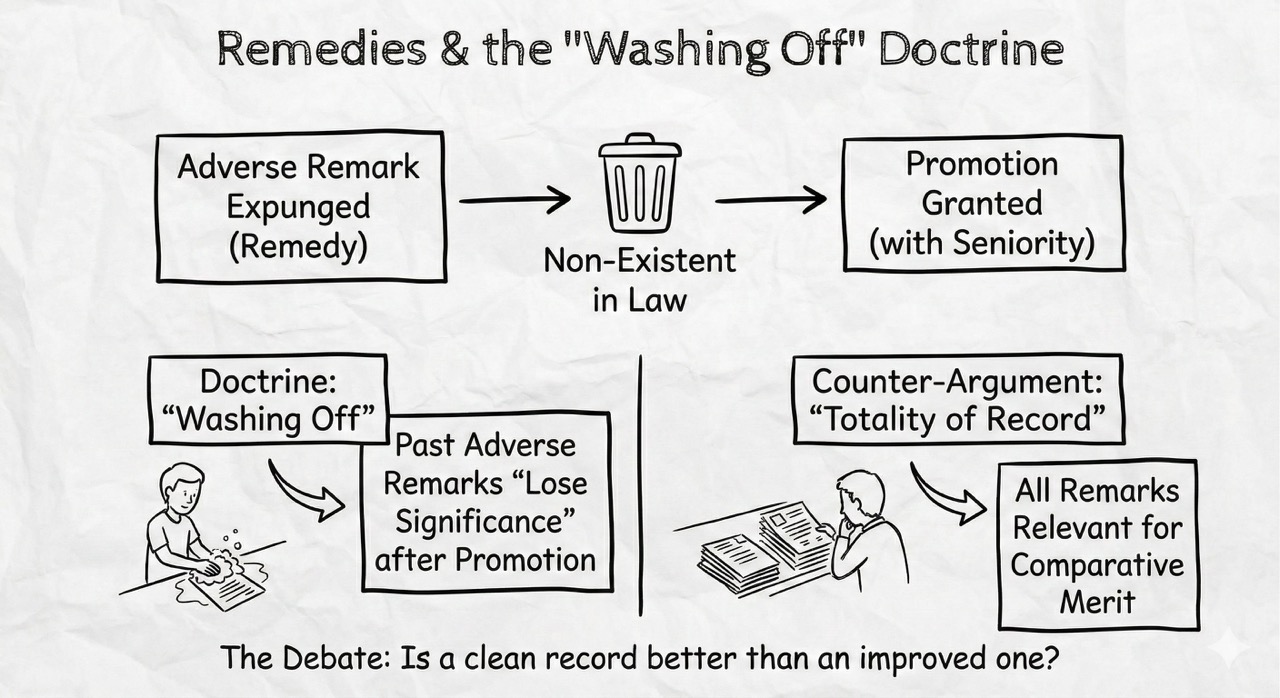

When an employee’s representation against an adverse remark is successful, the primary legal remedy is the expunction of that remark from their service record. This administrative remedy is complemented by the limited but vital role of judicial review, which serves as a crucial check to ensure fairness, objectivity, and adherence to procedure.

The legal effect of expunging an adverse remark is absolute. The Supreme Court, in UPSC v Hiranyalal Dev, has held that once expunged, the remarks “must be treated as non-existent in the eyes of law.” Consequently, it would be erroneous for any authority, including a Selection Committee, to consider such remarks when evaluating an employee’s career. If a promotion was previously denied based on a later-expunged entry, the employee is entitled to have their seniority restored from the date their juniors were promoted.

A complex legal question concerns whether another officer has the locus standi to challenge the expunction of remarks from a colleague’s ACR. The law on this point is unsettled. While the Supreme Court in Lakhi Ram v State of Rajasthan answered this question in the affirmative, a subsequent three-judge bench in Chandra Gupta v Secretary, Govt of India introduced significant uncertainty. After observing that the rules do not provide for such an objection, the Court confusingly concluded its judgment by stating that it had not decided the issue of the locus standi of an aggrieved officer. This leaves the question technically open, demonstrating the type of legal ambiguity that frequently arises in service jurisprudence.

Regarding the extent of judicial review, courts are generally loath to interfere with the content of ACRs or substitute their own judgment for that of reporting officers. However, judicial intervention is not excluded. Courts can and will intervene in cases involving “patent illegality, arbitrariness or lack of authority,” such as when an entry is rooted in bias or recorded in violation of prescribed procedures.

These procedural remedies ultimately determine the real-world impact of confidential reports on an employee’s career progression.

6. The Practical Impact: Promotion and the “Washing Off” Doctrine

The abstract legal principles governing ACRs translate into tangible and often career-defining consequences, particularly in the realm of promotion. The law has developed specific doctrines to address when adverse remarks can be used to deny promotion and when they are considered to have lost their relevance or sting over time.

First, it is a settled legal rule that an employee cannot be denied promotion based on uncommunicated adverse remarks. Such an action would be a clear violation of the principles of natural justice.

A more nuanced legal doctrine governs when past adverse entries are considered “wiped off” or rendered inconsequential. This “washing off” doctrine has been the subject of conflicting judicial pronouncements.

- The foundational principle was laid down in State of Punjab v Dewan Chuni Lal, where allowing an employee to cross an efficiency bar was held to render earlier adverse remarks irrelevant for subsequent disciplinary action.

- This principle was extended to promotions, but with conflicting results. In Brij Mohan Singh Chopra v State of Punjab, the Supreme Court held that “adverse entries…lose their significance on or after his promotion.” However, a contrary view was taken in Rajendra Singh Verma v Lt Governor (NCT of Delhi). The legal position appears to have settled in favour of the former view, as a three-judge bench in High Court of Judicature of Patna v Shyam Deo Singh expressly approved the position taken in Brij Mohan Singh Chopra.

However, this doctrine is not without a powerful counter-argument. A five-judge bench of the Orissa High Court in Ramesh Prasad Mahapatra v State of Orissa authoritatively distinguished the doctrine’s application. It reasoned that while past condoned acts are irrelevant for subsequent disciplinary action, the consideration for promotion is fundamentally different. For promotion, which involves a comparative assessment of merit, the “totality of the service record” is essential. The Court argued that an officer with a consistently clean record stands on a better footing than one with a poor early record, even if the latter was subsequently promoted. This distinction highlights that while an officer may be deemed fit to continue in service, their entire record remains relevant for comparative evaluation against peers.

Conclusion

The law on adverse confidential reports is a complex tapestry woven from administrative rules, constitutional principles, and decades of judicial interpretation. The core legal tenets that emerge are clear: the mandate for objectivity in recording entries; the critical “impact test” established in Dev Dutt, which prioritizes substance over form; the non-negotiable right to communication and representation rooted in natural justice; and an intricate jurisprudence governing the consequences of these reports. Ultimately, the jurisprudence surrounding ACRs represents a continuous judicial effort to temper the inherent subjectivity of administrative assessments with the inviolable principles of natural justice, ensuring that the machinery of the state serves, rather than subjugates, the rights of its employees.