- Constitutional mandate: Reservation is affirmative action to achieve substantive equality for SC, ST, and OBC.

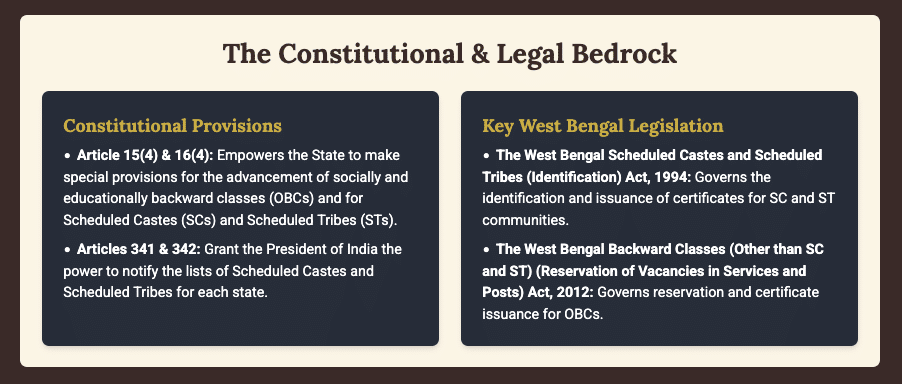

- Key provisions: Articles 15(4), 16(4), and 46 empower state measures for advancement and protection.

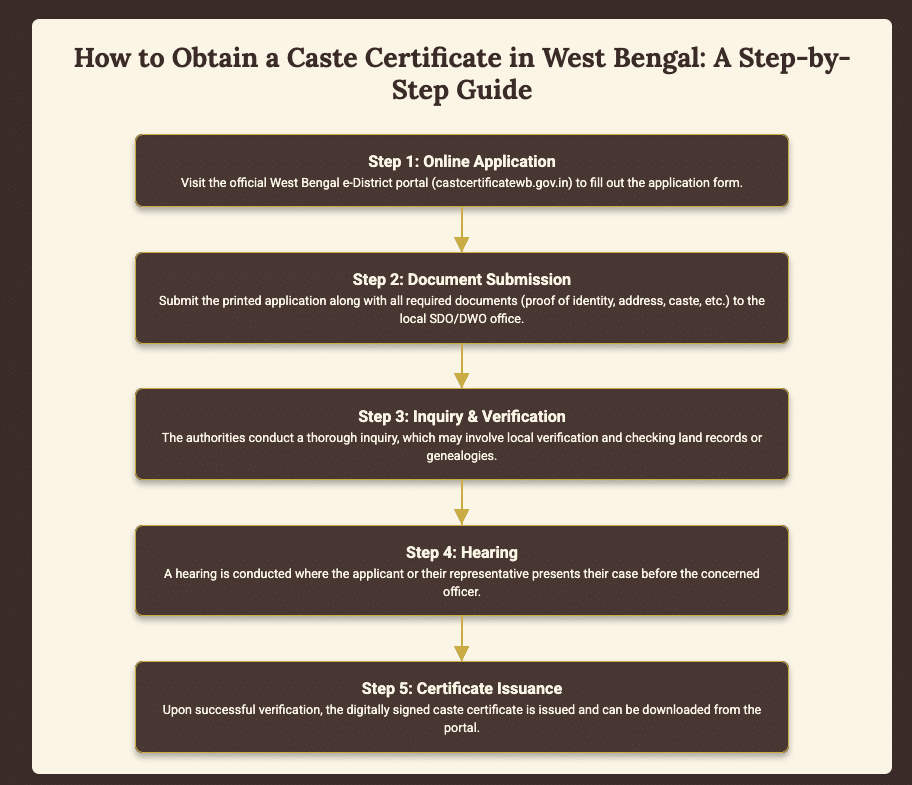

- Caste certificates: Legal proof for reservation benefits; issued by district authorities after rigorous document scrutiny and field inquiry.

- West Bengal law: The WB SC/ST (Identification) Act, 1994 sets SDO/DWO as issuing authorities with appeal and cancellation procedures.

- OBC controversy: Calcutta High Court struck down many OBC inclusions; the Supreme Court stayed that order pending final adjudication.

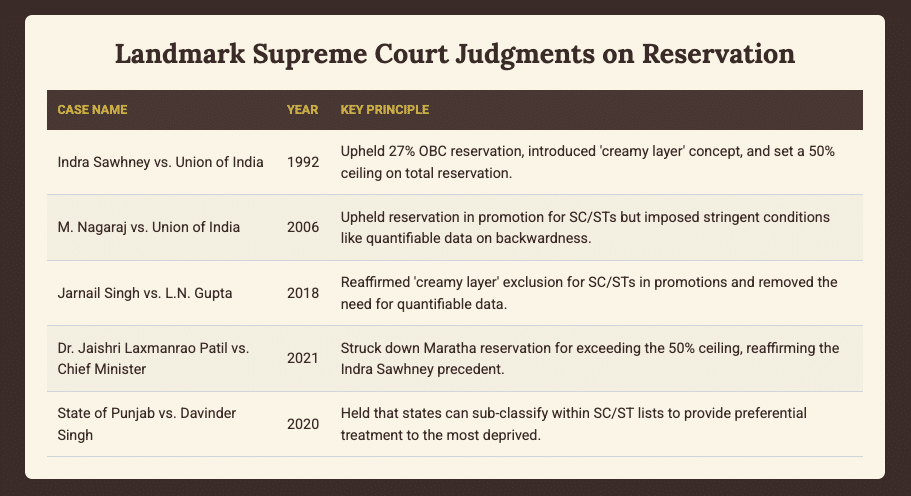

- Judicial limits: Supreme Court principles include the 50% ceiling, creamy layer, and strict rules on promotions (e.g., M. Nagaraj, Jarnail Singh).

- Remedies: Statutory appeals under the WB Act and writs (certiorari, mandamus) in High Court under Article 226 for wrongful rejection/cancellation.

A Comprehensive Legal Guide on Caste Certificates and Reservation in India: Procedure, Rights, and Remedies with a Special Focus on West Bengal

Part I: The Constitutional and Legal Framework of Reservation

Section 1: The Constitutional Mandate for Affirmative Action

1.1. Foundational Principles of Substantive Equality

The Indian Constitution is not merely a charter of rights ensuring formal equality; it is a transformative document aimed at achieving substantive equality for all its citizens. Central to this vision is the policy of reservation, a form of affirmative action or “positive discrimination,” designed to remedy centuries of historical injustice, social exclusion, and discrimination faced by certain communities.1 The objective is to uplift these historically disadvantaged sections of society—namely the Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC)—by providing them with preferential access to education, public employment, and political representation. This framework seeks to create a level playing field, ensuring that equality of opportunity is not a theoretical promise but a tangible reality.

1.2. Analysis of Key Constitutional Provisions

The bedrock of India’s reservation policy is a set of specific provisions within the Constitution that empower the State to take affirmative action. These provisions are not exceptions to the right to equality but are, in fact, instruments for its realization.

- Article 15(4): This clause empowers the State to make “any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes.” This provision was not part of the original Constitution but was introduced via the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951. This amendment was a direct legislative response to the Supreme Court’s judgment in State of Madras v. Smt. Champakam Dorairajan, AIR 1951 SC 226, which had struck down caste-based reservations in educational institutions. Article 15(4) thus became the constitutional basis for reserving seats in educational institutions.4

- Article 16(4): This is the cornerstone of reservation in public employment. It enables the State to make “any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which, in the opinion of the State, is not adequately represented in the services under the State.” This article provides the constitutional sanction for job quotas for SC, ST, and OBC communities.4

- Article 46: As a Directive Principle of State Policy, this article is fundamental to the governance of the country. It directs the State to “promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.” While not directly enforceable in a court of law, it provides the moral and political mandate for all affirmative action policies.4

- Other Safeguards: The constitutional framework for protecting and advancing these communities is comprehensive and includes several other key articles:

○ Article 17: Abolishes “Untouchability” and makes its practice in any form a punishable offense.4

○ Articles 330 & 332: Provide for the reservation of seats for SCs and STs in the Lok Sabha (House of the People) and the State Vidhan Sabhas (Legislative Assemblies), respectively, ensuring their political representation.4

○ Article 335: Stipulates that the claims of members of SCs and STs shall be taken into consideration in making appointments to public services, consistent with the maintenance of administrative efficiency.4

○ Articles 243D & 243T: Mandate reservation of seats for SCs and STs in every Panchayat and Municipality, ensuring their participation in local self-government.5

1.3. The Presidential Power of Identification and Notification

A crucial aspect of the constitutional scheme is the process of identifying which communities are to be designated as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. This power is vested exclusively with the President of India, creating a robust and uniform mechanism.

- Articles 341 & 342: Article 341(1) empowers the President, with respect to any State or Union Territory, and after consultation with the Governor, to specify by public notification the “castes, races or tribes” which shall be deemed to be Scheduled Castes in relation to that State or UT. Similarly, Article 342(1) grants the President the power to specify the “tribes or tribal communities” to be deemed Scheduled Tribes.12

- The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 & The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950: Exercising these powers, the President issued these two foundational orders which, for the first time, notified the official lists of SCs and STs for various states.12 It is critical to note that these lists are state-specific; a community may be listed as an SC in one state but not in another.

- The Parliamentary Mandate for Amendment: The constitutional mechanism establishes a dynamic yet controlled process. While the President notifies the initial list, Articles 341(2) and 342(2) explicitly state that any subsequent inclusion in or exclusion from these lists can only be done by an Act of Parliament. This two-step process—initial executive notification followed by exclusive legislative power for amendment—was deliberately designed. It grants the lists constitutional sanctity and insulates them from arbitrary changes by state or central executives, ensuring that any modification reflects a national consensus and undergoes legislative scrutiny. This makes the identity of SC/ST communities a matter of constitutional determination, a significant distinction from the process for identifying OBCs.

- Religious Criterion for SCs: Paragraph 3 of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, originally stipulated that “no person who professes a religion different from the Hindu religion shall be deemed to be a member of a Scheduled Caste”.19 This was later amended by Parliament to include persons professing the Sikh religion (in 1956) and the Buddhist religion (in 1990). However, individuals who have converted to Christianity or Islam are excluded from being recognized as Scheduled Castes, a matter that remains a subject of legal and social debate.15 No such religious bar applies to Scheduled Tribes.22

1.4. Distinguishing SC, ST, and OBC

The criteria for identifying communities under these three categories are distinct:

- Scheduled Castes (SC): The primary criterion for inclusion in the SC list is the historical and continuing social disability arising from the practice of “untouchability”.4

- Scheduled Tribes (ST): The criteria for identifying STs, as established by the Lokur Committee (1965), include indications of primitive traits, distinctive culture, geographical isolation, shyness of contact with the wider community, and general backwardness.23

- Other Backward Classes (OBC): This is a broader category of communities identified as being socially, educationally, and economically backward. The identification process, largely influenced by the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, is based on a composite set of indicators related to social status, educational attainment, and economic conditions.7

Section 2: The Architecture of Reservation Policy

Building upon the constitutional foundation, the specific architecture of reservation policy has been shaped by legislative acts, executive orders, and, most significantly, a series of landmark judicial pronouncements.

2.1. Quantum of Reservation

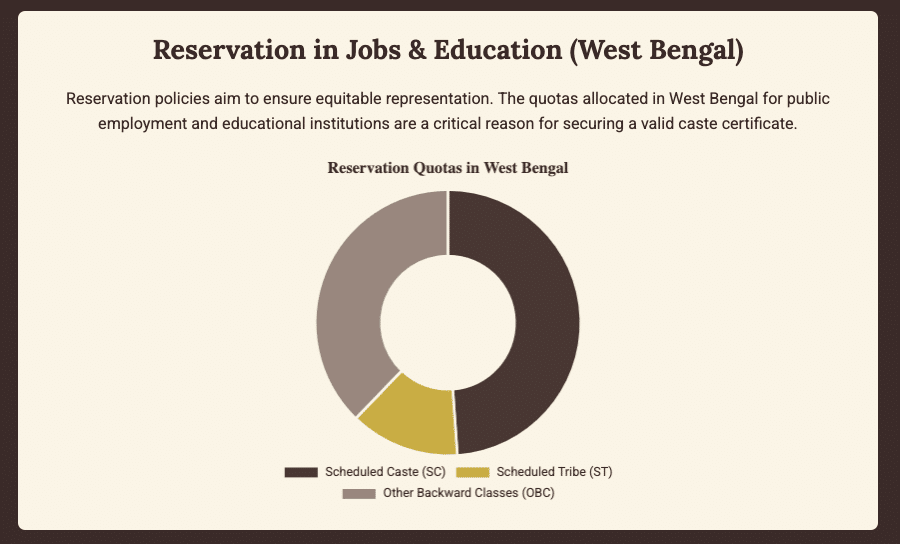

At the central level, the quantum of reservation in direct recruitment for civil posts and services is as follows 7:

| Category | Reservation Percentage |

| Scheduled Caste (SC) | 15% |

| Scheduled Tribe (ST) | 7.5% |

| Other Backward Classes (OBC) | 27% |

| Economically Weaker Section (EWS) | 10% |

| Total | 59.5% |

2.2. The Contentious Terrain of Reservation in Promotions

The issue of extending reservation benefits to promotions has been one of the most litigated aspects of affirmative action policy.

- Initial Position: The nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court in Indra Sawhney & Others v. Union of India, AIR 1993 SC 477, held that the scope of Article 16(4) was confined to initial appointments and did not permit reservation in matters of promotion.6

- Parliamentary Response: To counteract this judgment and restore reservation in promotions for SCs and STs, Parliament enacted a series of constitutional amendments. This sequence of legislative action and subsequent judicial review illustrates the dynamic interplay between the two branches of government. Parliament consistently sought to expand the scope of reservation, while the judiciary, while not striking down the amendments, imposed conditions to ensure they align with the broader constitutional principles of equality and efficiency.

○ 77th Amendment (1995): Inserted a new clause, Article 16(4A), to explicitly empower the State to make provisions for reservation in promotion for SCs and STs who, in the opinion of the State, are not adequately represented in public services.6

○ 81st Amendment (2000): Added Article 16(4B), which allows the State to treat unfilled reserved vacancies of a year (backlog vacancies) as a separate class of vacancies to be filled in any succeeding year. This clause crucially states that such vacancies will not be combined with the vacancies of the current year for determining the 50% ceiling, effectively insulating backlog vacancies from the quota limit.4

○ 85th Amendment (2001): Further amended Article 16(4A) to provide for “consequential seniority” to SC/ST candidates promoted through reservation. This meant that a reserved category candidate promoted earlier than a senior general category candidate would also be considered senior to them in the promoted cadre.11

- Judicial Scrutiny of Amendments:

○ M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 212: The constitutional validity of these amendments was challenged in this case. The Supreme Court upheld the amendments, but introduced a set of stringent conditionalities. It ruled that before granting reservation in promotion, the State must demonstrate with quantifiable data that there is: (i) backwardness of the class, (ii) inadequacy of representation of that class in public employment, and (iii) that the reservation would not compromise the overall efficiency of administration (as mandated by Article 335).6 This judgment effectively placed a judicial check on the executive’s power, requiring empirical justification for such policies.

○ Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta, (2018) 10 SCC 396: The court revisited the M. Nagaraj judgment. It modified the first condition, holding that since SCs and STs are constitutionally presumed to be backward, the State is not required to collect quantifiable data to prove their backwardness. However, the requirement to provide data on their inadequate representation in the specific cadre and to ensure administrative efficiency remained. In a significant development, the Court also extended the “creamy layer” principle to SCs and STs, ruling that affluent members of these communities could be excluded from the benefit of reservation in promotions.6

2.3. The 50% Ceiling Rule and the “Creamy Layer” Doctrine

Two other judicially evolved principles have profoundly shaped reservation policy:

- The 50% Ceiling: The Supreme Court, in the case of M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore, AIR 1963 SC 649, first opined that reservation should be “less than 50%”.28 This was solidified into a binding rule by the nine-judge bench in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992). The Court held that the total reservation quota should not exceed 50%, except in “extraordinary situations” involving communities in far-flung and remote areas. This ceiling is intended to balance the principle of affirmative action with the right to equality of opportunity for all citizens.1

- The “Creamy Layer” Doctrine: In the same Indra Sawhney judgment, the Supreme Court mandated the exclusion of the “creamy layer” from the benefits of OBC reservation. The rationale is that members of a backward class who have become socially and economically advanced are no longer in need of the crutch of reservation and should compete in the general category, allowing the benefits to percolate to the most deserving and marginalized sections of that class.37 This principle of exclusion applies to OBCs for both initial appointments and promotions. As noted above, the Jarnail Singh case extended this principle to SCs and STs in the context of promotions, a decision that continues to be a subject of intense legal and political discourse.8

Part II: Obtaining a Caste Certificate in India

Section 3: General Procedure for Application and Verification

3.1. The Caste Certificate as a Legal Instrument

A caste certificate is an official document issued by a competent government authority that certifies an individual’s membership in a specific Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), or Other Backward Class (OBC). It is the primary legal instrument that enables individuals to access the benefits of reservation in public employment, admission to educational institutions, and various welfare schemes launched by the central and state governments.43 The certificate serves as conclusive proof of an individual’s social status for the purposes of affirmative action.

3.2. Competent Authorities for Issuance

The issuance of caste certificates is a subject governed by respective state governments and union territory administrations. Consequently, the designated competent authorities vary across jurisdictions. Generally, these certificates are issued by executive magistrates at the district or sub-divisional level.13 Common authorities include the District Magistrate/Collector, Additional District Magistrate, Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM), or Tehsildar/Talukdar.44 In the state of West Bengal, the primary issuing authorities are the Sub-Divisional Officer (SDO) for the sub-divisions and the District Welfare Officer (DWO), Kolkata, for the area under the Kolkata Municipal Corporation.46

3.3. Standard Documentation and Evidence

While specific requirements may vary slightly from state to state, a standard set of documents is generally required to prove one’s claim. The burden of proof lies on the applicant. Key documents include 13:

- Proof of Identity: Aadhaar Card, Voter ID Card, PAN Card, Passport.

- Proof of Address: Ration Card, Utility Bills (Electricity/Water), Rent Agreement.

- Proof of Age/Birth: Birth Certificate, School Leaving Certificate, Admit Card of a Board Examination.

- Proof of Caste: This is the most critical component. The strongest evidence is a caste certificate issued to a paternal blood relative (e.g., father, grandfather, uncle, brother). In its absence, other documents like old land records (deeds), school admission registers of parents or grandparents mentioning the caste/community, or an extract from the village panchayat record can be submitted.

- Proof of Residence: Documents establishing that the applicant or their ancestors have been permanent residents of the state from a specific cut-off date. For SC/STs, this is often linked to the date of the Presidential Orders of 1950.22

- Affidavit: A self-declaration in a prescribed format affirming the details provided in the application.

- For OBC (Non-Creamy Layer): Additional documents like income certificates, salary slips of parents, or Income Tax Returns are required to establish that the applicant does not belong to the “creamy layer”.48

3.4. The Verification Process

The process of issuing a caste certificate is designed to be rigorous to prevent fraud. The typical workflow involves 22:

- Application Submission: The applicant submits the application form (either online or offline) along with all supporting documents to the designated office.

- Document Scrutiny: The concerned officials verify the submitted documents against the originals.

- Local Inquiry: A crucial step where a local revenue officer or social welfare inspector conducts a field verification. This may involve visiting the applicant’s residence, interviewing local community members or elders, and examining local records to confirm the applicant’s claim of caste and residence.

- Report and Recommendation: The inquiring officer submits a report to the competent authority.

- Final Decision: Based on the application, documents, and the inquiry report, the competent authority either issues the certificate or, if not satisfied, issues a written order of rejection, typically after giving the applicant an opportunity to be heard.

Furnishing false information or producing a fraudulent certificate to secure an appointment or admission is a serious offense. If discovered, it can lead to immediate termination from service or expulsion from the educational institution, along with criminal prosecution under the Indian Penal Code and relevant state laws.13

Section 4: Inclusion of New Communities in Reserved Lists

4.1. The Formal Procedure for Notification

The inclusion of a new community in the central list of SC, ST, or OBC is a formal, multi-stage process designed to ensure that the claims of backwardness are thoroughly vetted.

- Origination of Proposal: The process begins with a proposal or request from a State Government or Union Territory Administration.

- Scrutiny and Consultation:

○ For SCs and STs: The proposal is examined by the Union Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (for SCs) or Ministry of Tribal Affairs (for STs). It is then sent for comments to the Registrar General of India (RGI) and the respective National Commission—the National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) or the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST). A positive recommendation from all these bodies is generally required.23

○ For OBCs: The proposal is evaluated by the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC), a constitutional body under Article 338B. The NCBC assesses the community’s claim based on established criteria of social, educational, and economic backwardness, often conducting public hearings and studies before making its recommendation to the Union Government.24

- Cabinet Approval and Legislative/Executive Action:

○ Once the recommendations are finalized, the Union Government prepares a cabinet note.

○ For inclusion in the SC or ST list, a Bill to amend the relevant Presidential Order must be passed by both Houses of Parliament.12

○ For inclusion in the Central List of OBCs, the Cabinet’s approval is followed by a notification published in the Gazette of India by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.52

4.2. Practical Steps for Individuals from Newly Notified Communities

Once a community is officially included in a reserved list through a Gazette notification or an Act of Parliament, its members become eligible to apply for the corresponding caste certificate. While the application procedure remains the same as detailed in Section 3, the nature of the evidence required undergoes a significant shift.

The Gazette notification or the amending Act serves as conclusive legal proof of the community’s eligibility for reservation. The rigorous, evidence-based exercise to establish the community’s collective backwardness has already been completed at the national level by commissions and Parliament. Therefore, the inquiry by the local certificate-issuing authority (like an SDO) is not to re-evaluate the community’s status but is confined to a much simpler question: Is the applicant a genuine member of this newly notified community?

The applicant’s burden of proof is thus streamlined. Their primary task is to furnish documents that establish their personal affiliation with that specific community. Such evidence can include:

- School or college records where the community name is mentioned.

- Old land deeds or revenue records identifying the family’s community.

- Certificates or letters from recognized community associations or bodies.

- Testimonies from local elders during the field inquiry.

The Gazette Notification itself should be annexed to the application as the foundational document establishing the community’s legal status as SC, ST, or OBC.

Part III: A Deep Dive into West Bengal’s Legal Landscape

Section 5: The Statutory Regime in West Bengal

The issuance and regulation of caste certificates in West Bengal are governed by a specific state-level legal framework, primarily designed to streamline the process and prevent fraudulent claims.

5.1. The West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994

This is the principal legislation governing the identification of SC and ST persons in the state.51 Its key provisions are:

- Issuance of Certificate (Section 5): Designates the Sub-Divisional Officer (SDO) in the districts and the District Magistrate (or an authorized Additional District Magistrate) of South 24-Parganas for Kolkata as the competent certificate-issuing authorities.

- Power to Refuse (Section 7): Empowers the issuing authority to refuse a certificate in writing if not satisfied with the evidence, but only after giving the applicant a reasonable opportunity of being heard.

- Appeal against Refusal (Section 8): Provides a statutory appeal mechanism. An appeal against an SDO’s refusal lies with the District Magistrate. The decision of the appellate authority is final.

- Power to Cancel, Impound, or Revoke (Section 9): Authorizes the issuing authority to cancel a certificate if it is found to have been obtained by furnishing false information, misrepresentation, suppression of material facts, or forgery. This action can be taken suo motu or on the direction of the State Scrutiny Committee.

- Penalties (Section 10): Prescribes punishment of imprisonment up to six months or a fine up to two thousand rupees, or both, for knowingly obtaining a certificate through fraudulent means.

- State Scrutiny Committee and Vigilance Cell (Sections 8A & 8B): The Act provides for the constitution of a State Scrutiny Committee to verify the social status of certificate holders and a Vigilance Cell in each district to conduct inquiries, thereby creating a robust institutional mechanism for fraud detection.53

5.2. Governing Rules for OBCs

Unlike for SCs and STs, there is no separate comprehensive Act for the identification of OBCs in West Bengal. The process is governed by executive notifications and guidelines issued by the Backward Classes Welfare Department. A key notification (No. 347-TW/EC dated 13-07-1994) and subsequent updated guidelines clarify that the procedures and principles laid down in the SC/ST (Identification) Act, 1994, and its rules shall apply mutatis mutandis (with necessary modifications) to the identification of OBC persons.46

Furthermore, reservation for OBCs in public services and posts is governed by The West Bengal Backward Classes (Other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of Vacancies in Services and Posts) Act, 2012. This Act provides the statutory basis for the 17% reservation for OBCs in the state, bifurcated into Category A (More Backward) and Category B (Backward).58

5.3. Key Authorities and their Roles

The administrative hierarchy for caste certificate issuance in West Bengal is clearly defined:

- Certificate Issuing Authority:

○ Sub-Divisional Officer (SDO): For all sub-divisions in the districts.46

○ District Welfare Officer (DWO), Kolkata: For the jurisdiction of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation.46

- Recommending Authority: This is the authority that conducts the initial inquiry and recommends the case to the issuing authority.

○ Block Development Officer (BDO): For rural areas within a block.47

○ Deputy Magistrate: Authorized by the SDO for municipal areas (excluding Kolkata).60

- Appellate Authorities:

○ District Magistrate: Hears appeals against refusal orders passed by an SDO.51

○ Commissioner, Presidency Division: Hears appeals against refusal orders passed by the DWO, Kolkata.54

Section 6: A Step-by-Step Guide to Obtaining a Caste Certificate in West Bengal

The Government of West Bengal has streamlined the application process through a dedicated online portal, though it still requires a crucial offline component for verification.

6.1. The Online Application Portal

The official portal for applying for SC, ST, and OBC certificates is https://castcertificatewb.gov.in. This portal, managed by the Backward Classes Welfare Department, is the starting point for all new applications.61

6.2. Detailed Walkthrough of the Online Application Process

The online application requires careful attention to detail. The steps are as follows 45:

- Access the Portal: Visit castcertificatewb.gov.in and click on “Application for SC/ST/OBC Certificate.”

- Fill in Basic Details: Select your District, Sub-Division, and Municipality/Block.

- Select Category: Choose the category you are applying for (SC, ST, or OBC) and specify the exact caste/tribe/community from the dropdown list.

- Applicant’s Information: Enter your full name, father’s name, mobile number, email ID, Aadhaar number, and date of birth.

- Address Details: Provide your present and permanent address details, including village/ward, police station, post office, and PIN code.

- Paternal Blood Relative’s Certificate: This is a critical section. If a paternal blood relative has a caste certificate, provide their name, relationship to you, certificate number, and date of issue. This significantly strengthens the application.

- Local Referees: Provide the names and addresses of two local referees who can vouch for your identity and community status.

- Migration Details: Indicate if your family migrated from another state or country and provide details if applicable.

- Upload Photograph: Upload a recent passport-sized photograph in the specified format.

- Save and Print: After filling all details, click “Save and Continue.” The system will generate an Application Number. Review the application preview carefully, submit it, and print the auto-generated application form and the acknowledgement slip.

6.3. Post-Online Submission Procedure

The online submission is only the first step. The following offline procedure is mandatory for the application to be processed 47:

- Prepare the Physical File: Sign the printed application form. Gather self-attested photocopies of all required documents.

- Submit the Application: Submit the complete physical file (printed form + documents) to the appropriate office:

○ Block Development Officer (BDO) office for rural applicants.

○ Sub-Divisional Officer (SDO) office for municipal applicants.

○ District Welfare Officer (DWO) office for Kolkata applicants.

- Hearing and Verification: The office will schedule a hearing date. On this day, you must appear in person with all original documents for verification. An inquiry officer will conduct a local field inquiry to verify your residence and community claim.

- Issuance: Upon successful verification and recommendation, the SDO/DWO will issue a digitally signed caste certificate, which can be downloaded from the same portal using the application number.

6.4. Document Checklists

For SC/ST Applicants 48:

- Printed Application Form.

- Proof of Identity (Aadhaar/Voter ID/PAN Card).

- Proof of Residence (Ration Card/Utility Bill).

- Proof of Citizenship (Birth Certificate/Aadhaar Card).

- Proof of Permanent Residence in West Bengal since 10.08.1950 (for SC) or 06.09.1950 (for ST) (e.g., old land deed, parent’s voter card).

- Caste certificate of a paternal blood relative and a genealogical chart proving the relationship.

- Two passport-sized photographs.

For OBC Applicants 47:

- All documents listed for SC/ST applicants.

- Proof of Permanent Residence in West Bengal since 15.03.1993.

- Documents for Non-Creamy Layer Status:

○ Income certificate from employer/Panchayat Pradhan/Municipal Councillor.

○ Salary slips of parents for the last three consecutive financial years.

○ Income Tax Returns of parents for the last three consecutive financial years.

○ Certificate from the employer regarding the parents’ post status (Group A, B, C, D) if they are government/PSU employees.

Section 7: The Recent Controversy Surrounding the OBC List in West Bengal

The landscape of OBC reservation in West Bengal has recently been thrown into turmoil due to a significant legal battle between the Calcutta High Court and the State Government. This controversy is not merely a state-specific issue but reflects the larger national tensions surrounding the criteria and politics of reservation.

7.1. The Calcutta High Court’s Judgment (May 2024)

In a far-reaching judgment in May 2024, a division bench of the Calcutta High Court struck down the classification of 77 communities as Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and cancelled all OBC certificates issued in West Bengal after 2010 based on these classifications.69 The grounds for this drastic decision were twofold:

- Improper Criteria: The Court concluded that the inclusion of these communities, a majority of which were Muslim, was done primarily on the basis of religion, which it deemed the “sole criterion.” This, the Court held, was impermissible and amounted to a “fraud on the Constitution”.72

- Procedural Irregularity: The judgment found that the State Government had bypassed the statutory body, the West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes, in making these classifications. The Court ruled that the power to include communities in the OBC list could not be exercised through executive fiat without proper consultation and recommendation from the Commission, as mandated by law.70 This action was described as an “abuse of power”.73

7.2. The State Government’s Appeal and the Supreme Court’s Stay Order (July 2025)

The West Bengal government swiftly challenged the High Court’s order before the Supreme Court.72

- State’s Argument: The government argued that the High Court’s decision had brought numerous government appointments and admissions to a halt. It contended that the identification of backward classes is an executive function and does not require a legislative act for every inclusion.76

- Supreme Court’s Reasoning: On July 28, 2025, the Supreme Court stayed the High Court’s order, finding it “prima facie erroneous”.72 The apex court’s reasoning was rooted in established constitutional precedent. It observed that reservation is an “executive function” and that the nine-judge bench in the Indra Sawhney case had already settled that backward classes could be identified through executive directions. The Supreme Court was “surprised” that the High Court had insisted on a legislative process for what is a well-established executive power.74

7.3. Current Status and Implications

The Supreme Court’s stay means that, for the time being, the OBC certificates issued after 2010 remain valid, and the state’s revised OBC list can be acted upon. The apex court has directed the Calcutta High Court to constitute a special bench to hear the matter expeditiously.76 The current situation creates significant legal uncertainty for lakhs of OBC certificate holders whose status hangs in the balance pending the final adjudication. The core issue—whether the state’s identification process was flawed and whether religion was used as an impermissible proxy for social backwardness—remains to be decided. This case has become a critical test for the future of OBC reservation policy, particularly concerning the inclusion of minority communities, not just in West Bengal but across India.

Part IV: Legal Remedies and Judicial Intervention In case a caste certificate is rejected or revoked by the concerned authorities.

Section 8: Challenging the Revocation or Rejection of a Caste Certificate

When an application for a caste certificate is rejected or an existing certificate is cancelled, the aggrieved individual is not without recourse. Both statutory and constitutional remedies are available.

8.1. Statutory Appeal Mechanisms

The West Bengal SC/ST (Identification) Act, 1994, provides a clear, first-line remedy in the form of a statutory appeal. As per Section 8 of the Act, if an application is refused by the SDO, the applicant can file an appeal before the District Magistrate. If the refusal is by the DWO, Kolkata, the appeal lies before the Commissioner, Presidency Division. This appeal must be filed within a prescribed time limit and is to be disposed of within three months, after giving the appellant a reasonable opportunity of being heard. The decision of this appellate authority is final at the statutory level.51

8.2. Grounds for Cancellation and Challenge

A certificate can be cancelled by the issuing authority under Section 9 of the 1994 Act if it was obtained through fraudulent means, such as by furnishing false information, misrepresenting facts, or suppressing material information.51 An individual whose certificate is cancelled can challenge this order. The primary grounds for such a challenge are:

- Violation of Principles of Natural Justice: The most common ground is that the cancellation order was passed without giving the individual a proper notice or a fair opportunity to present their case and evidence.

- Arbitrariness or Perversity: The decision to cancel was made without any supporting evidence or was based on irrelevant considerations, making it arbitrary and legally unsustainable.

- Jurisdictional Error: The authority that cancelled the certificate did not have the legal power to do so. For instance, the Supreme Court in M/S Darvell Investment and Leasing (India) Pvt. Ltd. v. The State of West Bengal (2023) clarified the jurisdictional limits of the State Level Scrutiny Committee in West Bengal.79

Section 9: The Writ Jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court: A Practical Roadmap

If the statutory appeal fails or if the order of cancellation is passed in gross violation of legal principles, the ultimate remedy lies in approaching the High Court under its writ jurisdiction.

9.1. Invoking Article 226 of the Constitution

Article 226 of the Constitution of India grants every High Court extraordinary power to issue directions, orders, or writs to any person or authority, including the government, for the enforcement of Fundamental Rights and for “any other purpose”.80 The wrongful rejection of a caste certificate application or the arbitrary cancellation of an existing certificate directly infringes upon an individual’s rights under Article 14 (Right to Equality), Article 16 (Right to Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment), and can also impact their Article 21 (Right to Livelihood).

9.2. Choosing the Appropriate Writ

The two most relevant writs in such matters are:

- Writ of Certiorari: This writ is sought to quash an illegal, arbitrary, or jurisdictionally flawed order. If the SDO, District Magistrate, or Scrutiny Committee has passed an order cancelling a certificate in violation of natural justice or based on no evidence, a writ of certiorari can be prayed for to set aside that order.83

- Writ of Mandamus: This writ, meaning “we command,” is used to compel a public authority to perform its statutory duty. It can be sought to direct the authority to issue a certificate that has been wrongfully denied or to direct them to reconsider an application in accordance with the law after an illegal cancellation order has been quashed by certiorari.81 Often, a writ petition will pray for both certiorari and mandamus.

9.3. Drafting and Filing a Writ Petition

Filing a writ petition in the Calcutta High Court requires adherence to its specific procedural rules.

- Jurisdiction (Original Side vs. Appellate Side): The choice of jurisdiction depends on the location of the respondent authority. If the office of the authority that passed the impugned order (e.g., the SDO) is located outside the Ordinary Original Civil Jurisdiction of the High Court, the petition is filed on the Appellate Side. If it is within this jurisdiction (primarily concerning authorities located in central Kolkata), it is filed on the Original Side.80

- Structure of the Petition: A writ petition must be meticulously drafted and should typically include the following sections 80:

- Cause Title: Stating the jurisdiction, and the names and addresses of the petitioner(s) and respondent(s).

- Synopsis and List of Dates: A brief summary of the case and a chronological list of key events.

- Statement of Facts: A clear, concise, and chronological narration of the facts leading to the petition, with each fact supported by an annexed document.

- Grounds: Separate, numbered paragraphs detailing the legal arguments for why the impugned order is illegal (e.g., “For that the order is violative of the principles of natural justice…”).

- Averment: A mandatory declaration that no similar application has been filed before any other court on the same cause of action.

- Prayers: Specific and precise prayers asking the court for the desired relief (e.g., “to issue a Writ in the nature of Certiorari quashing the impugned order dated…;” “to issue a Writ in the nature of Mandamus commanding the respondents to issue the caste certificate…”).

- Procedural Requirements: The petition must be supported by an affidavit sworn by the petitioner. All relevant documents must be annexed. The prescribed court fees must be paid, and copies of the entire petition must be served upon all respondents before filing.82

9.4. The Path Forward

After filing, the petition is listed for a “Motion” hearing. If the court finds a prima facie case, it issues a “Rule,” calling upon the respondents to show cause as to why the reliefs prayed for should not be granted. The respondents (the State) then file their “Affidavit-in-Opposition,” to which the petitioner can file an “Affidavit-in-Reply.” The matter is then heard finally, and the court either makes the Rule absolute (grants the prayers) or discharges the Rule (dismisses the petition).81

Part V: Judicial Precedents and Expert Assistance

Section 10: Landmark Judgments on Reservation Policy

The law of reservation in India is almost entirely a product of judicial interpretation. The following table summarises some of the most influential Supreme Court judgments that have defined and redefined the contours of affirmative action.

| Sr. No. | Case Name & Citation | Year | Key Principles Laid Down / Subject Matter | Significance |

| 1 | State of Madras v. Champakam Dorairajan, AIR 1951 SC 226 | 1951 | Struck down caste-based reservation in educational institutions as violative of Article 29(2). | Led to the First Constitutional Amendment, which inserted Article 15(4) to validate such reservations.6 |

| 2 | M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore, AIR 1963 SC 649 | 1962 | Ruled that reservation should not exceed 50% and that caste cannot be the sole basis for determining backwardness. | First articulation of the 50% ceiling rule on reservations.28 |

| 3 | State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas, (1976) 2 SCC 310 | 1976 | Held that Article 16(4) is not an exception to Article 16(1) but an emphatic facet of the doctrine of equality. | Expanded the conceptual understanding of equality from formal to substantive, justifying affirmative action as a means to achieve equality.28 |

| 4 | Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, AIR 1993 SC 477 | 1992 | Upheld 27% reservation for OBCs; solidified the 50% ceiling rule; mandated the exclusion of the “creamy layer” from OBCs; and barred reservation in promotions. | The single most important judgment on reservation policy, setting the foundational principles that govern it to this day.6 |

| 5 | Kumari Madhuri Patil v. Addl. Commissioner, Tribal Development, (1994) 6 SCC 241 | 1994 | Laid down a comprehensive 15-point guideline for the issuance and verification of caste certificates and mandated the creation of Scrutiny Committees in states. | Created a standardized national framework for preventing fraudulent claims and ensuring the integrity of the certification process.92 |

| 6 | R.K. Sabharwal v. State of Punjab, (1995) 2 SCC 745 | 1995 | Introduced the ‘post-based roster’ system, replacing the ‘vacancy-based roster’, for calculating reserved posts. | Ensured that reservation is applied to the number of posts in a cadre and not just to the vacancies that arise, preventing over-representation.28 |

| 7 | Ajit Singh Januja v. State of Punjab (Ajit Singh-I), (1996) 2 SCC 715 | 1996 | Introduced the ‘catch-up rule’, stating that a senior general category employee, upon promotion, would regain seniority over a junior reserved category employee promoted earlier. | Attempted to balance the seniority claims between general and reserved category employees.25 |

| 8 | M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 212 | 2006 | Upheld constitutional amendments allowing reservation in promotion but imposed three conditions: quantifiable data on backwardness, inadequate representation, and administrative efficiency. | Acted as a judicial check on Parliament’s power, making reservation in promotion conditional upon empirical justification by the State.6 |

| 9 | Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India, (2008) 6 SCC 1 | 2008 | Upheld the constitutional validity of 27% reservation for OBCs in Central Government-funded educational institutions. | Extended the OBC reservation policy to higher education at the national level.28 |

| 10 | Chairman, FCI v. Jagdish Balaram Bahira, (2017) 8 SCC 670 | 2017 | Held that any benefit obtained on the basis of a fraudulent caste certificate is void ab initio and the person must be stripped of all advantages, including the job or degree obtained. | Overruled earlier judgments that allowed for equitable relief, taking a stringent stance against fraud in reservation.100 |

| 11 | Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta, (2018) 10 SCC 396 | 2018 | Modified M. Nagaraj by stating that states need not collect data on the backwardness of SCs/STs for promotions. Crucially, it applied the ‘creamy layer’ principle to SCs/STs for reservation in promotions. | Simplified one condition for promotion quotas but introduced the controversial creamy layer concept for SCs/STs.6 |

| 12 | Bir Singh v. Delhi Jal Board, (2018) 10 SCC 312 | 2018 | Held that a person belonging to an SC/ST in one state cannot claim reservation benefits in employment in another state where their community is not notified as SC/ST. | Affirmed the state-specific nature of SC/ST lists and limited the portability of reservation benefits.102 |

| 13 | B.K. Pavitra v. Union of India (II), (2019) 16 SCC 129 | 2019 | Upheld a Karnataka law providing consequential seniority based on a report that provided quantifiable data, thereby satisfying the Nagaraj conditions. | Demonstrated how a state could successfully justify its reservation in promotion policy by adhering to the Supreme Court’s data-driven requirements.104 |

| 14 | Mukesh Kumar v. State of Uttarakhand, (2020) 3 SCC 1 | 2020 | Ruled that reservation in appointments and promotions is not a fundamental right. It is an enabling provision, and a state cannot be directed to provide reservation. | Clarified that while the state is empowered to provide reservation, it is not obligated to do so, reinforcing executive discretion.6 |

| 15 | Chebrolu Leela Prasad Rao v. State of A.P., (2021) 11 SCC 401 | 2020 | Struck down a government order providing 100% reservation for Scheduled Tribes teachers in schools within Scheduled Areas as unconstitutional and violative of the 50% ceiling. | Reaffirmed the Indra Sawhney 50% cap and held that it applies even in Scheduled Areas.108 |

| 16 | Saurav Yadav v. State of U.P., (2021) 4 SCC 542 | 2020 | Clarified the interplay between vertical (SC/ST/OBC) and horizontal (e.g., women, PwD) reservations. Held that meritorious reserved candidates who score high enough to qualify in the general category must be placed there. | Ensured that reservation does not act as a barrier to meritorious candidates from reserved categories competing for open seats.110 |

| 17 | Dr. Jaishri Laxmanrao Patil v. The Chief Minister, Maharashtra, (2021) 8 SCC 1 | 2021 | Struck down the Maharashtra law granting reservation to the Maratha community as it breached the 50% ceiling without any “extraordinary circumstances.” Also held that only the President, through the NCBC, can identify SEBCs. | Reaffirmed the sanctity of the 50% ceiling rule and, at the time, centralized the power of identifying backward classes (later reversed by the 105th Amendment).112 |

| 18 | State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh, 2024 INSC 562 | 2024 | Held that states have the power to sub-classify within the SC and ST lists to provide preferential treatment to the most backward communities among them. | Paved the way for “reservation within reservation” for SCs/STs to ensure equitable distribution of benefits, referring the matter to a larger bench to overrule a contrary precedent.28 |

| 19 | P.A. Inamdar v. State of Maharashtra, (2005) 6 SCC 537 | 2005 | Ruled that the state cannot impose its reservation policy on unaided private (minority and non-minority) educational institutions. | Led to the 93rd Constitutional Amendment, which inserted Article 15(5) to enable reservations in private educational institutions.28 |

| 20 | Dayaram v. Sudhir Batham, (2012) 1 SCC 333 | 2012 | Re-examined and modified the guidelines in Madhuri Patil regarding the finality of Scrutiny Committee decisions and the bar on appeals. | Refined the procedure for caste certificate verification, clarifying the scope of judicial review over Scrutiny Committee orders.118 |

Section 11: Seeking Expert Legal Counsel

11.1. The Role of Specialized Legal Representation

The law surrounding caste certificates and reservation is a complex and constantly evolving field, intersecting constitutional law, administrative law, and service jurisprudence. Navigating the procedural requirements for obtaining a certificate, appealing a rejection, or challenging a cancellation in the High Court requires specialized legal knowledge and experience. An error in procedure or a poorly drafted petition can have serious consequences. Therefore, engaging expert legal counsel is not just advisable but often essential for the effective protection of one’s rights.

11.2. Introduction to Patra’s Law Chambers

For individuals and entities grappling with these intricate legal issues, Patra’s Law Chambers offers specialized expertise and comprehensive legal services.

- Overview: Established in 2020 by Advocate Sudip Patra, a distinguished alumnus of the Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, IIT Kharagpur, with advanced degrees from IIM Calcutta, the firm combines technical acumen with legal prowess. With a strong presence in both Kolkata and Delhi, the firm is strategically positioned to handle matters before the Calcutta High Court, other High Courts, and the Supreme Court of India.

- Areas of Expertise: Patra’s Law Chambers has a proven track record in handling a wide array of legal matters, including Civil, Criminal, and Company Law. The firm’s core strengths in Writ Litigation and Service Law make it exceptionally well-equipped to address legal challenges related to caste certificates, reservation policies, employment disputes, and administrative actions. The firm’s lawyers possess the requisite expertise to draft and argue complex writ petitions, handle appeals against administrative orders, and represent clients at all levels of the judicial system.

Whether you are facing a wrongful denial of a caste certificate, an arbitrary cancellation order, or discrimination in public employment, Patra’s Law Chambers provides dedicated and expert legal representation to safeguard your constitutional and statutory rights.

Contact Information:

- Firm Name: Patra’s Law Chambers

- Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: +91 890 222 4444 / +91 9044 04 9044

- Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor,

2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001

(Near Calcutta High Court)

- Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV,

Gali Shahid Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road,

Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Works cited

- Reservation in India – Explained in Layman’s Terms – ClearIAS, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.clearias.com/reservation-in-india/

- A Legal Analysis of India’s Reservation Policies and Their Constitutional Ramifications – IJFMR, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.ijfmr.com/papers/2025/2/38242.pdf

- Historical Evolution and Constitutional Framework of Reservation in India – The Law Advice, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.thelawadvice.com/articles/historical-evolution-and-constitutional-framework-of-reservation-in-india

- Constitutional Safeguards – National Commission for Scheduled Castes, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://ncsc.nic.in/constitutional-safeguards

- Special Provisions Relating to Certain Classes (Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes) – Jus Scriptum Law, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.jusscriptumlaw.com/post/special-provisions-relating-to-certain-classes-scheduled-castes-scheduled-tribes-and-other-backwa

- Reservation – Atish Mathur, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.atishmathur.com/polity/reservation

- What is the Reservation Percentage in India? – BYJU’S, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/reservation/

- Reservation in India – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reservation_in_India

- 3 Special Provisions of the CONSTITUTION OF INDIA for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes ARTICLE 15: – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/documnts/07-07-2017-09-47-15.pdf

- PROVISION FOR SCs, STs, OBCs & MINORITIE – Shomish.com, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://shomish.com/study-materials.php/provision-for-scs,-sts,-obcs-&-minoritie

- Reservation system in India: Is it indispensable ? – International Journal of Law, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.lawjournals.org/assets/archives/2023/vol9issue6/9220-1701928662406.pdf

- Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheduled_Castes_and_Scheduled_Tribes

- Caste Certificate in India | Application Process – IndiaFilings, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.indiafilings.com/learn/caste-certificate-in-india/

- List of Scheduled Castes | Department of Social Justice and Empowerment – Government of India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://socialjustice.gov.in/common/76750

- 1 THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950 C.O. 19 In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of article 341 of th, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/scorders-updated-30062016.pdf

- THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950 – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/documnts/07-07-2017-11-33-12.pdf

- EXAMINING THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULE CASTE) ORDER, 1950 – HeinOnline, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/injlolw8§ion=144

- THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950]1 – S3waas, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/01/2023010994.pdf

- Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 – Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/CONSTITUTION%20(SC)%20ORDER%201950%20dated%2010081950.pdf

- The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order 1950 – Punjab Govt. Notification, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://punjabxp.com/wp-content/uploads/constitution-sc-order-1950.pdf

- VOLUME-I (Part 4) | Legislative Department | India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://legislative.gov.in/document-category/volume-i-part-4/

- No. 35/1/72-R.U. (SCT.V) Government of India/Bharat Sarkar Ministry of Home Affairs/Grih Mantralaya New Delhi-110001, Dated, the, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/guide-certificate636017830879050722.pdf

- Inclusion Into SC List – PIB, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=115783

- Other Backward Class – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other_Backward_Class

- Reservation in Promotion: Court in Review, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/reservation-in-promotion-court-in-review/

- Reservation in Promotion – National Commission for Scheduled Castes, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://ncsc.nic.in/storage/special_events/qaGTFkfUq3crTg6omWEXrqjxNkYVBXrXAJPFl5Q1.pdf

- Article 16 in Constitution of India – Indian Kanoon, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/211089/

- Court cases related to reservation in India – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Court_cases_related_to_reservation_in_India

- Reservation in Promotion – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/cases/jarnail-singh-v-lacchmi-narain-gupta-reservation-in-promotion-case-background/

- M Nagaraj v Union of India – Case Analysis – Testbook, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/m-nagaraj-v-union-of-india

- www.scobserver.in, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/reservation-in-promotion-court-in-review/#:~:text=Nagaraj%20v%20UOI,in%20Promotion%20to%20SCs%2FSTs.

- M. Nagaraj and Others v. Union of India 2007 – LegalBots.in, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://legalbots.in/blog/m-nagaraj-and-others-v-union-of-india-2007

- M. Nagaraj v. Union of India (2006): Landmark Judgment on Reservation & Equality | Dhyeya Law, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.dhyeyalaw.in/m-nagaraj-and-others-v-union-of-india-and-others-2006-8-scc-212

- Jarnail Singh vs. Lachhmi Narain Gupta (2018) – JuryScan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.juryscan.in/jarnail-singh-vs-lachhmi-narain-gupta-2018/

- Case study: Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta & Ors. – Legal Wires, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://legal-wires.com/case-study/case-study-jarnail-singh-v-lachhmi-narain-gupta-ors/

- 50% cap on reservation – Atish Mathur, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.atishmathur.com/polity/50%25-cap-on-reservation-

- The Landmark Judgment: Indra Sawhney vs Union of India and Its Impact on Reservation Policies – Sleepy Classes, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://sleepyclasses.com/indra-sawhney-vs-union-of-india/

- reservation in – Indian Kanoon, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=reservation%20in%20%20

- Indira Sawhney v Union of India: Landmark Judgement, Facts and Key Guidelines – Shiksha, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.shiksha.com/law/articles/indira-sawhney-v-union-of-india-case-blogId-209502

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indra_Sawhney_%26_Others_v._Union_of_India#:~:text=Union%20of%20India%20held%20that,11%20indicators%20to%20ascertain%20backwardness.

- Creamy layer – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creamy_layer

- Creamy Layer Reservation System – Drishti Judiciary, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.drishtijudiciary.com/editorial/creamy-layer-reservation-system

- Caste Certificate in India: Importance, Application Process, and Key Documents Required, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.legalkart.com/legal-blog/caste-certificate-in-india-importance-application-process-and-key-documents-required

- Caste Certificate Issuing Authority in India, Their Role & Significance – Digit Insurance, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.godigit.com/life-insurance/caste-certificate/caste-certificate-issuing-authority

- Domicile Certificate in West Bengal – 5 Step Guide | IndiaFilings, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.indiafilings.com/learn/west-bengal-caste-certificate/

- Issue of SC/ST/OBC Certificates – Anagrasarkalyan | Backward Classes Welfare Department, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/Bcw/ex_page/5

- Updated Guidelines for Issuance of OBC Certificates – WBXPress, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://wbxpress.com/guidelines-issuance-obc-certificates/

- Check List For Caste Certificate Documents | PDF – Scribd, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/451361115/Check-List-for-Caste-Certificate-documents-converted

- List of Documents Required for Caste Certificate in India – Digit Insurance, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.godigit.com/life-insurance/caste-certificate/documents-required-for-caste-certificate

- Rvisd Guidelines SC ST Cert | PDF | Government Information – Scribd, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://ru.scribd.com/document/190362373/Rvisd-Guidelines-Sc-St-Cert

- West Bengal Act XXXVIII of 1994 | India Code, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/14596/1/1994-38.pdf

- About Addition of Caste to OBC list: UPSC Current Affairs – IAS Gyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/addition-of-casts-to-central-obc-list

- Acts and Rules on Caste/Tribe Identification – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/documnts/07-07-2017-07-07-20.pdf

- 123 Acts and Rules on Caste/Tribe Identification (i) IDENTIFICATION ACT GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOT – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/documnts/07-07-2017-09-56-44.pdf

- The West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994 Act 38 of 1994 – PRS India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_states/west-bengal/1994/ActNo-38of1994-WB.pdf

- West Bengal Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Identification) Act, 1994, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1764540/the-west-bengal-scheduled-castes-and-scheduled-tribes-identification-act-1994/2496054/

- Government of West Bengal – Backward Classes Welfare Department – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/documnts/07-07-2017-07-18-02.pdf

- Backward Classes Welfare Department – Anagrasarkalyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/bcw/pages/3

- West Bengal Act XXXIX of 2012 – India Code, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/14368/1/2012-39.pdf

- west bengal scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (identification) rules, 1995 – LegitQuest, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.legitquest.com/act/west-bengal-scheduled-castes-and-scheduled-tribes-identification-rules-1995/CE80

- West Bengal Caste Certificate – How to Apply Online – BankBazaar, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.bankbazaar.com/govt-utility/caste-certificate-west-bengal.html

- Caste Certificate | Bankura District, Government of West Bengal | India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://bankura.gov.in/service/caste-certificate/

- Caste Certificate | Jhargram District, Government of West Bengal | India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://jhargram.gov.in/service/online-application-of-caste-certificate/

- Anagrasarkalyan | Backward Classes Welfare Department, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://anagrasarkalyan.gov.in/

- How to Apply Online for SC/ST/OBC Caste Certificate in West Bengal 2025 I SC ST OBC Caste Certificat – YouTube, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2q4-Q9WIJd4

- West Bengal SC/ST OBC Certificate Application Guide – Print Friendly, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.printfriendly.com/document/west-bengal-scst-obc-certificate-application-guide

- Updated Guidelines for Issuance of SC/ ST Certificates – WBXPress, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://wbxpress.com/guidelines-issuance-sc-st-certificates/

- Caste Certificate – WBXPress, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://wbxpress.com/subject/caste-certificate/

- Calcutta HC stays West Bengal’s OBC reclassification | SCC Times, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/06/20/calcutta-hc-stays-west-bengal-obc-reservation-reclassification-legal-news/

- Major Blow to Bengal Government, Calcutta HC Cancels 5 Lakh OBC Certificates Issued Since 2010 – Law Trend, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://lawtrend.in/calcutta-hc-deals-major-blow-to-bengal-government-cancels-5-lakh-obc-certificates-issued-since-2010/

- Calcutta High Court Cancels OBC Certificates Issued in West Bengal After 2010, Scraps OBC Classification of 37 Communities – LEGALIT Tools, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://legalit.ai/calcutta-high-court-cancels-obc-certificates-issued-in-west-bengal-after-2010-scraps-obc-classification-of-37-communities/

- Supreme Court stays High Court order freezing West Bengal’s new …, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/supreme-court-stays-calcutta-hc-order-on-west-bengal-obc-list/article69864349.ece

- ‘Fraud on power’ — Calcutta HC order scrapping nearly 5 lakh OBC certificates issued in Bengal – ThePrint, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://theprint.in/judiciary/fraud-on-power-calcutta-hc-order-scrapping-nearly-5-lakh-obc-certificates-issued-in-bengal/2100431/

- Supreme Court stays Calcutta High Court order which stayed new OBC List in West Bengal, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.newsonair.gov.in/supreme-court-stays-calcutta-high-court-order-halting-bengals-revised-obc-list/

- Supreme Court stays Calcutta HC order on West Bengal OBC list, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2025/Jul/28/supreme-court-stays-calcutta-hc-order-on-west-bengal-obc-list

- Supreme Court Stays Calcutta High Court Order Blocking New OBC …, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://lawbeat.in/supreme-court-news-updates/supreme-court-stays-calcutta-high-court-order-blocking-new-obc-list-in-west-bengal-1514172

- ‘Totally erroneous’: Supreme Court on Calcutta HC stay on Bengal govt’s OBC list expansion, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/supreme-court-revokes-calcutta-high-court-stay-on-bengal-governments-obc-list-expansion-prnt/cid/2115407

- SC Backs CM Mamata’s ‘OBC List’? ‘Erroneous’ Calcutta HC Faces CJI Ire: Bengal Govt’s Win? TMC Says – YouTube, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u54hn9zsBC4

- Supreme Court Sets Aside High Court’s Decision on Caste Certificate Cancellation Jurisdiction – CaseMine, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/supreme-court-sets-aside-high-court%E2%80%99s-decision-on-caste-certificate-cancellation-jurisdiction/view

- Guide to Filing a Writ Petition in the Calcutta High Court – Patras Law Chamber, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://patraslawchambers.com/guide-to-filing-a-writ-petition-in-the-calcutta-high-court/

- Exploring Writ Jurisdiction of Calcutta High Court – Patras Law Chamber, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://patraslawchambers.com/writs-under-the-calcutta-high-court-a-comprehensive-legal-analysis/

- WHAT IS WRIT PETITION? HOW CAN YOU FILE ONE IN THE COURT?, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://alc.edu.in/blog/what-is-writ-petition-how-can-you-file-one-in-the-court/

- Matters at Hon’ble High Court: – A.L.L.O.W.B, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://allowb.org/assets/pdfs/courtmatters/fc2.pptx

- Decoding The Writ Of Certiorari – Jyoti Judiciary Coaching, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.jyotijudiciary.com/decoding-the-writ-of-certiorari/

- “Correction of Quasi-Judicial Decisions: Writ of Certiorari” – Pen Acclaims, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://penacclaims.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Kushagra-Chandel.pdf

- Writ Of Mandamus: Legal Imperatives And Doctrinal Limitations – IJCRT.org, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2507507.pdf

- Rules of High Court at Calcutta relating to Applications under Article 226 of The Constitution of India – LatestLaws.com, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.latestlaws.com/bare-acts/state-acts-rules/west-bengal-state-laws/rules-of-high-court-at-calcutta-relating-to-applications-under-article-226-of-the-constitution-of-india/

- FORMAT OF WRIT PETITION A SYNOPSIS AND LIST OF DATES (Specimen enclosed) B FROM NEXT PAGE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA ORIGINAL – S3waas, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ec0490f1f4972d133619a60c30f3559e/uploads/2024/01/2024011726.pdf

- Procedure for Filing a Writ Petition in India – LawyerINC, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://lawyerinc.net/learning/what-is-the-procedure-for-filing-a-writ-petition-in-india/

- 692_Case analysis NM Thomas.docx – ProBono India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://probono-india.in/Indian-Society/Paper/692_Case%20analysis%20NM%20Thomas.docx

- State of Kerala v/s. N M Thomas – ProBono India, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://probono-india.in/research-paper-detail.php?id=692

- Kumari Madhuri Patil And Another v. Addl. Commissioner, Tribal Development And Others | Supreme Court Of India | Judgment | Law | CaseMine, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5609ac9fe4b014971140f562

- Memorial Respodent | PDF | Supreme Court Of India | Estoppel – Scribd, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/663473670/Memorial-Respodent

- Legal Analysis of Recent Judgments on Reservation Policies in India | SCC Blog, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/04/19/legal-analysis-of-recent-judgments-on-reservation-policies-in-india-legal-research-legal-news-updates/

- R.K. Sabharwal and Ors. vs. State of Punjab and Ors. (10.02.1995 – CLPR, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://clpr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/9.-R.K.-Sabharwal-and-Ors.-Vs.-State-of-Punjab-and-Ors.pdf

- Ajit Singh vs State Of Punjab – 2006 0 Supreme(P&H) 2257, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://supremetoday.ai/doc/judgement/02300026921

- Ajit Singh (II) v. State of Punjab, (1999) 7 SCC 209 – Aashayein Judiciary, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.alec.co.in/judgement-page/ajit-singh-ii-v-state-of-punjab-1999-7-scc-209

- Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. Union of India – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashoka_Kumar_Thakur_v._Union_of_India

- www.quimbee.com, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.quimbee.com/cases/ashoka-kumar-thakur-v-union-of-india#:~:text=Ashoka%20Kumar%20Thakur%20(plaintiff)%20challenged,prohibited%20by%20the%20Indian%20constitution.

- Chairman And Managing Director FCI vs Jagdish Balaram Bahira – 2017 0 Supreme(SC) 625, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://supremetoday.ai/doc/judgement/00100059552

- FCI Vs JAGDISH BAHIRA Final 2 | PDF | Appeal | Certiorari – Scribd, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/784095031/FCI-Vs-JAGDISH-BAHIRA-Final-2-1

- Pan-India Reservation in Union Territories: Insights from Bir Singh v. Delhi Jal Board (2018), accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/pan-india-reservation-in-union-territories:-insights-from-bir-singh-v.-delhi-jal-board-(2018)/view

- Justice Nazeer’s Notable Judgments: A Consistent Presence on Constitution Benches, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/justice-nazeers-notable-judgments-a-consistent-presence-on-constitution-benches/

- BK Pavitra v Union of India (2019) – LawBhoomi, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://lawbhoomi.com/bk-pavitra-v-union-of-india-2019/

- BK Pavitra v. Union of India (2017) 4 SCC 620 – Praṇav | प्रणव, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://pranavsaksena.com/posts/BK-Pavitra-v.-Union-of-India-2017/

- Case Commentary on Mukesh Kumar v. the State of Uttarakhand: Kamphilya Pallapati & Anulekha.M – ILSJCCL, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://journal.indianlegalsolution.com/2020/10/15/case-commentary-on-mukesh-kumar-v-the-state-of-uttarakhand-kamphilya-pallapati-anulekha-m/

- Mukesh Kumar Vs The State Of Uttarakhand – Right of Promotion is contingent upon the discretion of the State Government, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://viamediationcentre.org/readnews/NjA=/Mukesh-Kumar-Vs-The-State-Of-Uttarakhand-Right-of-Promotion-is-contingent-upon-the-discretion-of-the-State-Government

- A Case Of Judicial Oversight: critiquing Chebrolu Leela Prasad Rao V State Of A.P., accessed on October 14, 2025, https://pclshnluchapter.weebly.com/the-pcls-blog/a-case-of-judicial-oversight-a-critique-of-chebrolu-leela-prasad-rao-v-state-of-ap

- 100% Reservation for STs: 3 Must Reads – Supreme Court Observer, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.scobserver.in/journal/100-reservation-for-sts-3-must-reads/

- Horizontal and vertical quotas – IAS Gyan, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/horizontal-and-vertical-quotas

- Merit in Reservation – Sanskriti IAS, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.sanskritiias.com/uploaded_files/pdf/sanskritiias.comMerit%20in%20Reservation.pdf

- Madhya Pradesh urges Supreme Court to treat 50% quota cap as ‘flexible’ – The Hindu, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/madhya-pradesh-urges-supreme-court-to-treat-50-quota-cap-as-flexible/article70117558.ece

- The Case of the Maratha Reservations: Jaishri Laxmanrao Patil v. Chief Minister of State of Maharashtra – Constitutional Law Society, NUJS, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://wbnujscls.wordpress.com/2021/10/20/the-case-of-the-maratha-reservations-jaishri-laxmanrao-patil-v-chief-minister-of-state-of-maharashtra/

- State of Punjab v Davinder Singh (2024) Case Analysis – Testbook, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/state-of-punjab-vs-davinder-singh

- Reservation & Sub-Classification of SC/STs | State of Punjab v Davinder Singh | Most Imp Judgment – YouTube, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P2ER0Z7BJqk

- publications.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://publications.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/995/1/Some%20Constitutional%20Battles%20in%20the%20Field%20of%20Education2016Issue%20XXV.pdf

- PA Inamdar vs State of Maharashtra – Case Analysis – Testbook, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://testbook.com/landmark-judgements/pa-inamdar-vs-state-of-maharashtra

- Dayaram v. Sudhir Batham And Others | Supreme Court Of India | Judgment – CaseMine, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5609af01e4b0149711415529

- DAYARAM Vs. SUDHIR BATHAM – REGENT COMPUTRONICS PVT. LTD., accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.the-laws.com/Encyclopedia/browse/Case?caseId=001102900100&title=dayaram-vs-sudhir-batham