- Wills are legal documents that dictate asset distribution after death, following the Indian Succession Act, 1925.

- A valid Will must have testamentary capacity, be executed with free will, and meet certain formal requirements.

- Probate is the legal process validating a Will, essential for enforcing a testator's wishes in West Bengal.

- In West Bengal, probate is mandatory for Wills made by Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, or Jains.

- Calcutta High Court's jurisdiction includes granting probate, and its Original Side hears testamentary matters.

- The probate process involves drafting a petition, financial formalities, and notifying all interested parties.

- Judgments shape probate law, addressing issues like suspicious circumstances and the burden of proof in Will validity.

A Complete Guide to Probate Law in India & Procedures in Calcutta High Court (2025)

-

Creditor and contributor of this article:

Patra’s Law Chambers:

About Us:

Patra’s Law Chambers is a law firm with offices in Kolkata & Delhi, offering comprehensive legal services across various domains. Established in 2020 by Advocate Sudip Patra (Advocate, Supreme Court of India & Calcutta High Court) an alumnus of the Prestigious Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, IIT Kharagpur ,with Post Graduate diploma in Business Law from IIM Calcutta, the firm specializes in Civil, Criminal, Writs,High Court Matters, Trademark, Copyright, Company, Tax, Banking, Property disputes, Service law, Family law, and Supreme Court matters.You can know more about us in here

Kolkata Office:

NICCO HOUSE, 6th Floor, 2, Hare Street, Kolkata-700001 (Near Calcutta High Court)

Delhi Office:

House no: 4455/5, First Floor, Ward No. XV, Gali Shahid

Bhagat Singh, Main Bazar Road, Paharganj, New Delhi-110055

Website: www.patraslawchambers.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +91 890 222 4444/ +91 7003 715 325

Part I: The Cornerstone of Succession – Understanding Wills in India

The transfer of property from one generation to the next is a fundamental aspect of civil society, governed by a structured legal framework to ensure order and prevent disputes. At the heart of this framework lies the concept of testamentary succession—the disposition of property according to the expressed wishes of the deceased. The primary instrument for this is the Will, a document of profound legal significance. Understanding its definition, essential components, and various forms is the first step in navigating the complexities of inheritance and probate law in India.

A. The Legal Definition of a Will: More Than Just a Document

A Will, or testament, is the legal instrument through which an individual dictates the distribution of their assets after their demise. The Indian Succession Act, 1925, which is the principal legislation governing this area for most communities in India, provides a precise definition.

According to Section 2(h) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, a “Will” is defined as “the legal declaration of the intention of a testator with respect to his property which he desires to be carried into effect after his death”.1

This definition contains two vital elements. Firstly, it is a “legal declaration,” which signifies that for the declaration of intent to be valid, it must strictly conform to the procedures and formalities prescribed by law.2 Secondly, its operative power is posthumous; the Will remains a mere declaration of intent during the testator’s lifetime and only becomes legally effective upon their death.2 This ambulatory nature means that a Will can be altered or revoked by the testator at any point before their death, provided they remain competent to do so.2 The last validly executed Will is the one that is given legal effect.

It is important to note that the Indian Succession Act, 1925, governs Wills made by Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, and Christians. The law of testamentary succession for Muslims is distinct and is governed by their personal law (Shariat), not the Indian Succession Act.3

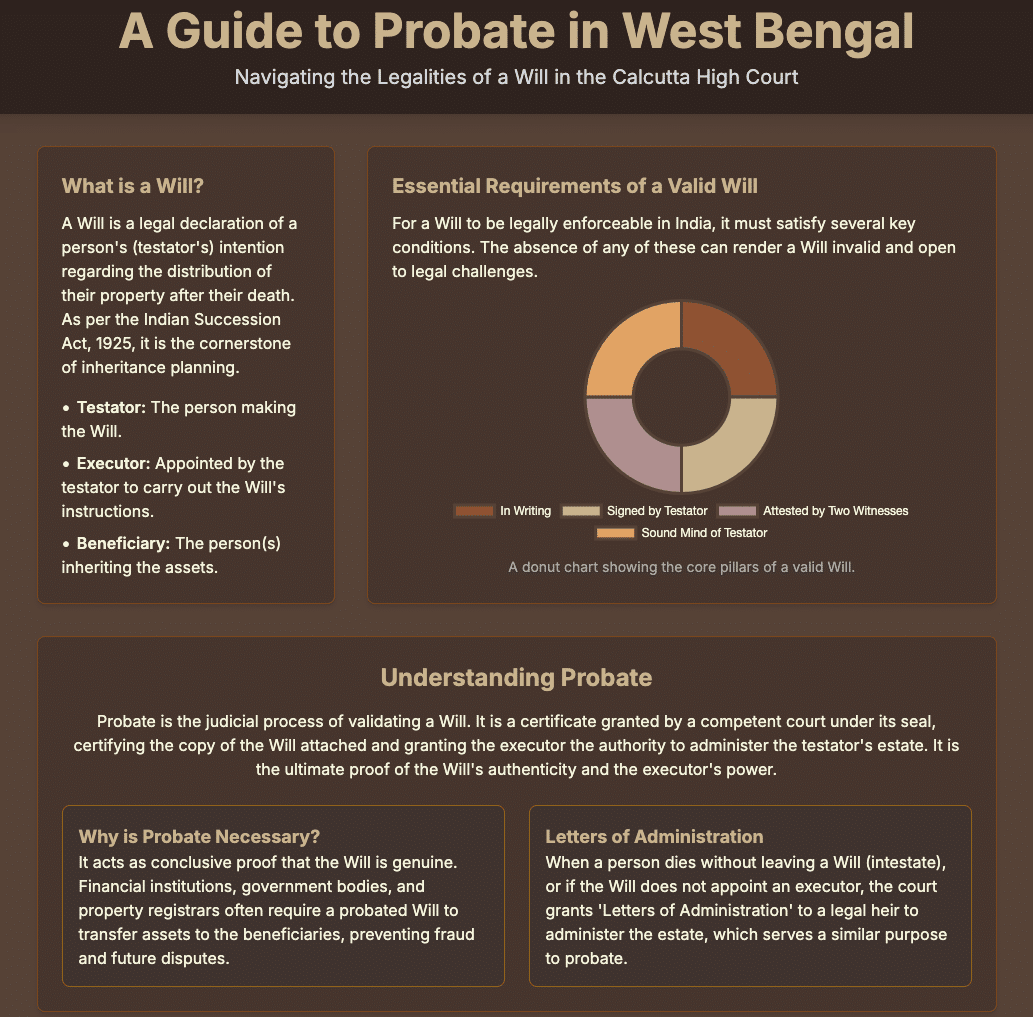

B. The Pillars of a Valid Will: The Non-Negotiable Essentials

For a Will to be upheld by a court of law, it must satisfy a set of stringent, non-negotiable conditions. The failure to meet any one of these essential requirements can render the document invalid and open to legal challenge during probate proceedings. These pillars are designed to ensure that the Will is a true reflection of the testator’s final wishes, made freely and with full understanding.

1. Testamentary Capacity

The foundation of a valid Will is the testator’s capacity to make it. The law requires the testator to be of sound mind and not a minor at the time of executing the Will.4 A person who is ordinarily of unsound mind may make a valid Will during an interval of lucidity.4 The legal test for a “sound disposing mind” is not merely about being conscious but involves the ability to comprehend three key aspects: the nature of the act of making a Will, the extent of the property being disposed of, and the moral claims of those who are being included or excluded from the inheritance.9

2. Free Will and Consent

A Will must be the voluntary expression of the testator’s wishes. Section 61 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, explicitly states that a Will, or any part of it, caused by fraud, coercion, or such importunity that takes away the free agency of the testator, is void.2 The document must be executed without any undue influence from beneficiaries or other parties, ensuring it is a product of the testator’s own volition.5

3. Formal Requirements of Execution (Section 63)

The law prescribes a specific ceremony for the execution of a Will to prevent fraud and ensure authenticity. These formal requirements, detailed in Section 63 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, are a frequent point of contention in probate suits and must be strictly adhered to. The procedural elements are not arbitrary rules but are causally linked to the core purpose of probate: ensuring the document reflects the testator’s true and final intention. They are statutory safeguards designed to create a verifiable event, providing a high evidentiary barrier against future claims of forgery, coercion, or lack of capacity.

- In Writing: The Will must be a written document. Oral Wills are generally not valid, except in the limited case of Privileged Wills.11

- Signature or Mark: The testator must sign the Will or affix their mark (such as a thumb impression). Alternatively, some other person can sign the Will on the testator’s behalf, but this must be done in the testator’s presence and by their direction. The signature or mark must be so placed that it appears it was intended to give effect to the writing as a Will.4

- Attestation by Witnesses: This is perhaps the most critical formal requirement. The Will must be attested by two or more witnesses. Each witness must have:

- Seen the testator sign or affix their mark; OR

- Seen the other person sign the Will in the testator’s presence and by their direction; OR

- Received from the testator a personal acknowledgment of their signature or mark.Furthermore, each witness must sign the Will in the presence of the testator.4 It is not legally required for the witnesses to be present at the same time or to sign in each other’s presence, but they must both sign in the testator’s presence.6

4. Clarity and Certainty

The language of the Will must be clear and unambiguous. The intentions of the testator regarding the property and the beneficiaries should be expressed with enough clarity to be understood and acted upon.3 Vague or uncertain dispositions can lead to the failure of the bequest.

C. An Overview of Will Types in India

While the fundamental principles remain the same, the Indian Succession Act recognizes different types of Wills based on the circumstances of their creation.

- Unprivileged Wills: This is the most common type of Will, made by ordinary citizens. It must strictly comply with all the formal requirements laid down in Section 63 of the Act, as detailed above.4

- Privileged Wills (Sections 65 & 66): These are an exception to the rule, applicable only to a soldier employed in an expedition, an airman so employed, or any mariner at sea. Given the perilous circumstances they face, the law relaxes the formal requirements. A Privileged Will can be in writing or made by word of mouth and does not require the strict attestation process of an Unprivileged Will.2

- Other Forms: Indian law also accommodates other specialized forms of Wills, including:

- Conditional or Contingent Wills: These Wills take effect only upon the happening or non-happening of a specified event.4

- Joint Wills: A single document created by two or more persons to dispose of their property. It typically takes effect after the death of all testators.5

- Mutual Wills: Two or more persons agree to make Wills in a particular manner, creating a binding agreement between them.10

- Holograph Wills: A Will written entirely in the testator’s own handwriting. While this can add to its authenticity, it must still be executed and attested as per the requirements of Section 63.5

Part II: Probate – The Judicial Seal of Authenticity

Once a testator passes away, the Will they have left behind is not automatically legally enforceable. It is merely a statement of their intentions. To transform this statement into a legally binding directive, it must undergo a judicial process of validation known as probate. This process is of paramount importance, especially in a jurisdiction like West Bengal, where it is often a mandatory prerequisite for the transfer of property.

A. What is Probate? The Court’s Official Sanction

Probate is the legal and judicial process of proving the validity of a Will. The term finds its definition in Section 2(f) of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, which defines it as “the copy of a Will certified under the seal of a court of competent jurisdiction with a grant of administration to the estate of the testator”.13

In simpler terms, probate is the official recognition by a court that the document produced is the last and genuine Will of the deceased and that the executor named therein is legally authorized to administer the estate.13 The court examines the Will to ensure it was executed in accordance with all legal formalities and that the testator had the requisite testamentary capacity and was not under any coercion or undue influence. If the court is satisfied, it grants probate, which serves as conclusive proof of the Will’s validity and the executor’s authority.14

A crucial legal nuance, often misunderstood, is that a probate proceeding does not decide questions of title to the property. The probate court is only concerned with whether the Will is genuine and duly executed.15 It does not determine whether the testator owned the property they bequeathed. The grant of probate merely perfects the executor’s right to represent the estate; it does not confer ownership.13 Any disputes regarding title must be adjudicated in a separate civil suit.

B. The Mandate for Probate in West Bengal

While obtaining probate is advisable across India to prevent future disputes, in certain jurisdictions, it is a legal mandate. West Bengal is one such jurisdiction.

Under the combined reading of Section 213 and Section 57 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, it is mandatory to obtain probate of a Will if it was made by a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, or Jain:

- Within the territorial limits of West Bengal (formerly the Presidency of Bengal); or

- Outside these territories, but dealing with immovable property situated within them.14

This legal mandate has profound practical implications. It elevates the probate process from a mere procedural formality to a substantive gateway for exercising inheritance rights in West Bengal. Without a grant of probate, no right as an executor or a legatee can be established in any court of law.16 This means a beneficiary under an unprobated Will in Kolkata cannot legally transfer the bequeathed property, cannot file a suit to evict a tenant from it, and cannot compel a bank to transfer the deceased’s funds. The Will remains legally inert until it is validated by the court. This creates a mandatory two-step process for succession: first, the instrument of succession (the Will) must be validated through probate; second, the validated instrument (the Grant of Probate) can be used to claim rights over the property. This reality makes meticulous Will drafting and proactive estate planning critically important in West Bengal, as a flawed Will that fails probate can result in the estate being distributed as per the laws of intestacy, potentially defeating the testator’s wishes entirely.

C. Probate vs. Letter of Administration: A Critical Distinction

The terms “Probate” and “Letter of Administration” are often used in the context of estate settlement, but they are not interchangeable. They apply in different circumstances and grant authority to different individuals.

- Probate: A probate is granted exclusively to the executor who has been explicitly named by the testator in the Will itself.13 This is governed bySection 222 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925. The grant of probate is an affirmation of the authority that the testator personally bestowed upon their chosen representative.

- Letter of Administration: A Letter of Administration is granted by the court in situations where there is a vacuum in the management of the estate. This occurs primarily in two scenarios:

- Intestacy: When a person dies without leaving a valid Will, the court appoints an administrator (usually a legal heir) to manage and distribute the estate according to the applicable laws of succession (e.g., the Hindu Succession Act, 1956).21

- Will without a functional Executor: When a Will exists, but it fails to name an executor, or the named executor is legally incapable, refuses to act, or has predeceased the testator, the court will appoint an administrator to execute the Will’s provisions. In this case, the document granted is called a “Letter of Administration with the Will Annexed”.19

In essence, probate validates a testator’s choice of executor, while a Letter of Administration is the court’s appointment of an administrator to fill a void.

Part III: Navigating the Jurisdiction of the Calcutta High Court

The Calcutta High Court, as the oldest High Court in India, possesses a unique and extensive jurisdiction in testamentary matters, rooted in its historical foundation and codified by statute. For any individual seeking to file for probate in West Bengal, understanding this jurisdiction is crucial to determining the correct legal forum for their application.

A. The Original Side Testamentary Jurisdiction: A Historical Legacy

Established on July 1, 1862, the Calcutta High Court’s authority in probate cases is not a recent development but a legacy of its colonial charter.24 This power is primarily derived from

Clause 34 of the Letters Patent of 1865, a constitutional document issued by the British Crown that established the High Court’s powers. Clause 34 specifically conferred “Testamentary and Intestate Jurisdiction” upon the High Court.26

This jurisdiction is exercised by the High Court’s Original Side, which is empowered to hear cases as a court of first instance, much like a trial court. Historically, this “Ordinary Original Civil Jurisdiction” was limited to the Presidency Town of Calcutta.25 However, in testamentary matters, this jurisdiction has a much wider reach.

B. Concurrent Jurisdiction: High Court vs. District Court

The modern statutory framework affirms and defines the High Court’s historical jurisdiction. Section 300 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, is the key provision. It states that the High Court shall have concurrent jurisdiction with the District Judge in the exercise of all powers related to granting probate and letters of administration.27

This principle of “concurrent jurisdiction” means that a petitioner has a choice of forum. An application for probate can be filed either:

- In the Calcutta High Court, whose testamentary jurisdiction under the Letters Patent extends throughout the entire state of West Bengal 24, or

- In the court of the District Judge within whose jurisdiction the deceased had a “fixed place of abode” or where any part of their property (movable or immovable) is situated, as per Section 270 of the Act.26

This choice is not merely a procedural option but a significant strategic decision. Filing in the Calcutta High Court’s Original Side provides access to a specialized judicial environment. The High Court has its own detailed procedural rules for testamentary matters (Chapter XXXV of the Original Side Rules) and is presided over by judges with extensive experience in complex commercial and succession cases.25 This can be highly advantageous for high-value estates, cases involving intricate legal questions, or Wills that are likely to be contested. Conversely, for a smaller, uncontested estate located entirely within a specific district, filing in the local District Court may be more practical and cost-effective, avoiding the logistical challenges of litigation in Kolkata.

C. The Interplay with the City Civil Court

The jurisdictional landscape within Kolkata itself has an additional layer of complexity due to the City Civil Court. For a period, amendments to the City Civil Court Act, 1953, carved out an exclusive jurisdiction for the City Civil Court for certain civil and testamentary matters arising exclusively within its territorial limits, thereby temporarily ousting the High Court’s original jurisdiction for those specific cases.27

However, a critical exception remains: if the deceased testator had any property, however small, or a fixed place of residence outside the territorial limits of the City Civil Court but within West Bengal, the Calcutta High Court’s overarching jurisdiction under Clause 34 of the Letters Patent is triggered.27 This allows the petitioner to file the probate application in the High Court, even if the bulk of the estate is within the city. This nuance is vital for practitioners to determine the correct forum and avoid preliminary objections on jurisdiction.

Part IV: A Step-by-Step Guide to Probate Proceedings in the Calcutta High Court (Original Side)

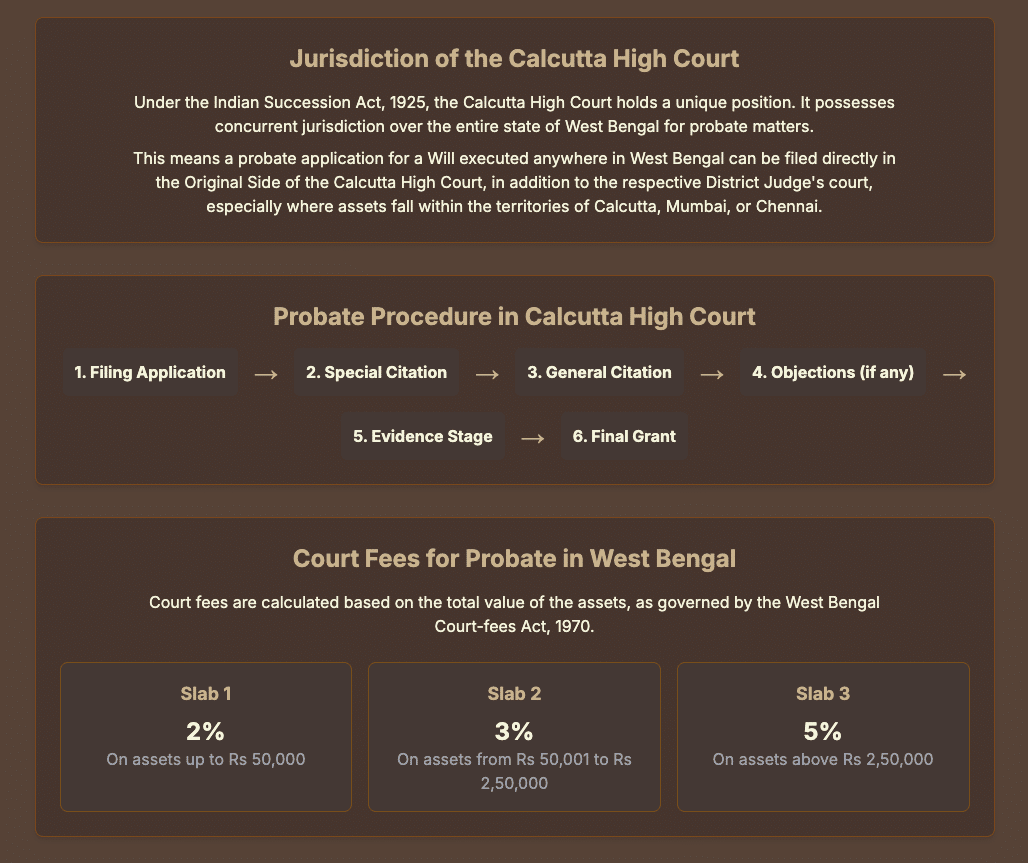

The process of obtaining probate from the Original Side of the Calcutta High Court is governed by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, the West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970, and, most specifically, by Chapter XXXV of the Calcutta High Court (Original Side) Rules, 1914. The procedure is a system of escalating scrutiny, designed to be efficient for undisputed Wills while providing a robust framework for resolving contested ones.

Step 1: Initiation – Drafting and Filing the Petition

The probate journey begins with the preparation and filing of a formal petition by the executor named in the Will.

- Drafting the Petition: The petition must be meticulously drafted in English, adhering to the requirements of Section 276 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925. It must state:

- The time and place of the testator’s death.

- That the document annexed is the testator’s last Will and testament.

- That the Will was duly executed.

- The total value of the assets likely to come into the petitioner’s hands.

- That the petitioner is the executor named in the Will.

- The names, addresses, and relationships of all the legal heirs and next-of-kin of the deceased, as they are entitled to be notified.14

- Essential Documents to be Annexed: The petition is incomplete without the following documents:

- The Original Will: The court must be presented with the original testamentary instrument.13

- Official Death Certificate: A certified copy of the testator’s death certificate issued by the competent authority.14

- Affidavit of Assets: A comprehensive schedule of all movable and immovable properties of the deceased, with their valuations, in the format prescribed by Schedule III of the West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970.47

- Affidavit of one Attesting Witness: While not mandatory at the filing stage, an affidavit from one of the witnesses to the Will, confirming the due execution, significantly strengthens the initial application and can expedite the process in non-contentious cases.

- Petitioner’s Identity and Address Proof: Standard KYC documents of the executor.44

The application, upon filing, is assigned a case number, typically prefixed with PLA (Probate, Letters of Administration).37

Step 2: Financial Formalities – Valuation and Court Fees

Upon filing, the petitioner must comply with the financial requirements stipulated by law.

- Valuation: The petitioner must submit a detailed valuation of the estate’s assets in the prescribed format (Annexure A for assets and Annexure B for debts/liabilities).47 This valuation forms the basis for calculating the court fees.

- Court Fees: The court fees are calculated ad valorem (as a percentage of the net value of the estate) according to the slab rates provided in Schedule I, Article 10 of the West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970.47 The fees are progressive, with higher percentages applied to higher asset values. For instance, the rate is 2% for the first slab, rising to 7% for the portion of the estate exceeding five lakhs of rupees.47 While a nominal fee is paid upon filing the application, the substantial ad valorem fee must be paid before the final Grant of Probate is issued by the court.39

Step 3: Notifying Interested Parties – The Role of Citations

A probate grant is a judgment in rem, meaning it is binding on the entire world. To ensure fairness and transparency, the court mandates that all potentially interested parties are given notice of the proceedings. This is achieved through the issuance of citations.

- Special Citations: The court directs the issuance of personal notices, known as special citations, to all legal heirs and next-of-kin of the deceased who would have been entitled to a share in the estate had the testator died without a Will. This service provides them with a formal opportunity to appear before the court and raise objections.50

- General Citations: In addition to personal notices, the court orders the publication of a General Citation in a newspaper with wide circulation in the locality where the deceased resided.13 This serves as a public notice to any other potential claimants or creditors. The format for this advertisement is prescribed in the Original Side Rules (Form No. 5, Chapter XXXV, Rule 12).39

The proper issuance and service of citations are of paramount importance. A failure to cite a necessary party is considered a substantive defect in the proceedings and constitutes a “just cause” for the revocation of a probate grant under Section 263 of the Act.50

Step 4: The Two Paths of a Probate Case

The procedural journey of a probate case is a system of escalating scrutiny. It begins as a summary verification but contains a built-in trigger—the caveat—that can transform it into a full adversarial trial. This structure efficiently processes undisputed Wills while reserving rigorous judicial examination for disputed ones.

A. The Non-Contentious Route (Grant in Common Form)

If the period for entering objections expires after the service of special and general citations and no one comes forward to challenge the Will, the proceeding remains a non-contentious PLA.37 The judge will examine the petition and the annexed documents. If satisfied that the Will was duly executed and all legal formalities have been complied with, the court will pass an order granting probate. This is known as a grant in “common form.”

B. The Contentious Route (Grant in Solemn Form)

The path diverges the moment an objection is formally lodged.

- Entering a Caveat: Any person who has an interest in the estate, however slight, can challenge the grant by filing a Caveat in the prescribed format (Form No. 12, Chapter XXXV, Rule 24).39 This acts as a formal notice to the court to not grant probate without first hearing the caveator.53

- Affidavit in Support of Caveat: The filing of a caveat must be followed by an Affidavit in Support within eight days, as per the Original Side Rules.36 This affidavit must clearly state the caveator’s interest in the estate and the specific grounds on which the Will is being challenged (e.g., forgery, undue influence, lack of testamentary capacity).55 If this affidavit is not filed, the caveat may be discharged.55

- Transformation into a Testamentary Suit (TS): The moment the affidavit in support of the caveat is filed, the nature of the proceeding changes fundamentally. The non-contentious PLA is converted into a contentious Testamentary Suit (TS).37 The petitioner (executor) becomes the Plaintiff, and the caveator becomes the Defendant. The matter is then placed before the appropriate bench for trial as a regular civil suit.

Step 5: The Trial – Proving the Will in “Solemn Form”

In a testamentary suit, the Will must be proven in “solemn form,” which involves a full trial with evidence and arguments from both sides.

- Burden of Proof: The entire burden of proof rests on the Plaintiff (the propounder of the Will). They must satisfy the conscience of the court that the document is the last Will of a free and capable testator.58

- Examination of Attesting Witnesses: This is the cornerstone of the trial. As per Section 68 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, the Plaintiff must call at least one of the attesting witnesses to the stand to prove the Will’s execution.63 The witness must testify to the requirements ofSection 63 of the Indian Succession Act—that they saw the testator sign (or acknowledge the signature) and that they signed the Will in the testator’s presence.64 The direct, sworn testimony of an attesting witness is considered powerful evidence, often outweighing the opinion of a handwriting expert.55

- Navigating “Suspicious Circumstances”: If the Defendant successfully raises circumstances that cast suspicion on the Will’s authenticity, the Plaintiff’s burden becomes significantly heavier. They must provide clear and cogent evidence to remove every suspicion. Common suspicious circumstances that courts scrutinize include:

- The primary beneficiary playing an active and prominent role in the preparation or execution of the Will.58

- Unnatural bequests or the unjust exclusion of close family members, like a spouse or children, without any stated reason.66

- The testator being in a frail physical or mental state at the time of execution.71

- A shaky, doubtful, or uncharacteristic signature of the testator.66

Step 6: The Conclusion – Judgment and Grant of Probate

Following the conclusion of the trial, where both parties have presented their evidence and arguments, the court delivers its judgment.

- Judgment: If the Plaintiff successfully discharges their burden of proof and satisfies the court of the Will’s validity, the court will pass a decree in their favor.

- Grant of Probate: Once the judgment is delivered, the Plaintiff must pay the full ad valorem court fees as assessed. Upon payment, the Registry of the High Court will issue the formal Grant of Probate. This document consists of a certified copy of the Will attached to a certificate from the court, sealed with the court’s seal.14 This grant is the executor’s ultimate legal authority to administer the estate according to the Will’s terms.

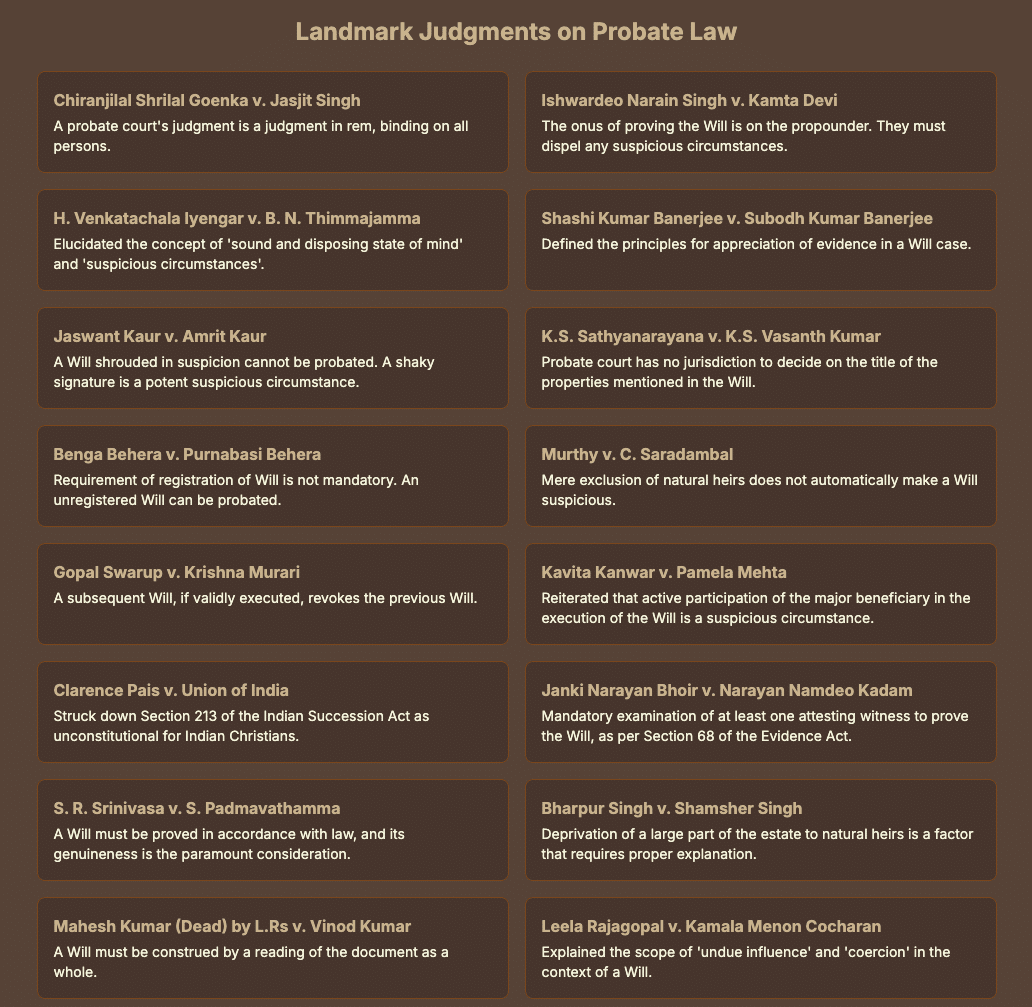

Part V: Landmark Judgments Shaping Indian Probate Law

The principles governing probate law are not derived from statute alone but have been meticulously shaped by the judiciary over decades. The following judgments are cornerstones of Indian testamentary jurisprudence, providing crucial guidance on the proof, validity, and administration of Wills. This table organizes these seminal cases by the core legal principle they address, serving as an invaluable quick-reference tool for understanding the key legal precedents.

| Case Name & Citation | Core Legal Principle Established |

| On Proof of Will & Suspicious Circumstances | |

| H. Venkatachala Iyengar v. B.N. Thimmajamma, AIR 1959 SC 443 | The foundational case defining “suspicious circumstances” and establishing that the propounder of the Will bears the heavy burden of removing all legitimate doubts to satisfy the court’s conscience.58 |

| Shashi Kumar Banerjee v. Subodh Kumar Banerjee, AIR 1964 SC 529 | Clarified that the propounder must prove the testator’s sound testamentary capacity and due execution of the Will. In the absence of suspicious circumstances, formal proof may suffice.58 |

| Rani Purnima Debi v. Kumar Khagendra Narayan Deb, AIR 1962 SC 567 | Held that registration of a Will does not by itself dispel suspicious circumstances, especially when the dispositions are unnatural and the registration process itself is questionable.75 |

| Smt. Jaswant Kaur v. Smt. Amrit Kaur, (1977) 1 SCC 369 | Established that the complete and unexplained exclusion of a natural heir (like a wife) is a significant suspicious circumstance that the propounder must explain.58 |

| Ramchandra Rambux v. Champabai, AIR 1965 SC 354 | Reinforced that unnatural bequests favoring a distant relative over close family members are a major red flag, increasing the burden of proof on the propounder.62 |

| Rabindra Nath Mukherjee v. Panchanan Banerjee, (1995) 4 SCC 459 | Explained that disinheritance of natural heirs is the very purpose of a Will and is not, by itself, a suspicious circumstance unless it is coupled with other dubious factors.77 |

| Sushila Devi v. Pandit Krishna Kumar Misra, (1971) 3 SCC 146 | Affirmed that superficial doubts (like the quality of paper used for the Will) are not sufficient to invalidate a Will if its execution is otherwise proven by credible evidence.78 |

| Kavita Kanwar v. Pamela Mehta, (2021) 11 SCC 209 | A modern reiteration of principles, holding that active participation by a major beneficiary in the Will’s execution is a grave suspicious circumstance.66 |

| On Testamentary Capacity | |

| Gorantla Thataiah v. Thotakura Venkata Subbaiah, AIR 1968 SC 1332 | Held that a Will executed when the testator was in a feeble physical and mental state, with the propounder taking a prominent role, is invalid for lack of sound disposing mind.67 |

| Madhukar D. Shende v. Tarabai Aba Shedage, (2002) 2 SCC 85 | Stated that mere suspicion or conjecture about the testator’s mental state is not enough to invalidate a Will; there must be concrete evidence of lack of testamentary capacity.79 |

| On Jurisdiction & Nature of Probate | |

| Chiranjilal Shrilal Goenka v. Jasjit Singh, (1993) 2 SCC 507 | A landmark ruling establishing that the Probate Court has exclusive jurisdiction to decide on the genuineness of a Will. This issue cannot be decided by a civil court or through arbitration.80 |

| Ishwardeo Narain Singh v. Kamta Devi, AIR 1954 SC 280 | Clarified that the scope of a probate proceeding is limited to determining the genuineness and due execution of the Will, not the title of the testator to the properties mentioned therein.15 |

| On Revocation of Probate | |

| Anil Behari Ghosh v. Smt. Latika Bala Dassi, AIR 1955 SC 566 | Detailed the grounds for revocation of probate under Section 263 for “just cause,” holding that non-citation of an heir is not sufficient unless it is shown to be a substantive defect or part of a fraudulent scheme.83 |

| Southern Bank Ltd. v. Kesardeo Ganeriwalla, AIR 1958 Cal 377 | A key Calcutta High Court judgment holding that grant of probate without citing a party who has an interest in the estate is a just cause for revocation.50 |

| On Proof and Evidence | |

| Gopal Swarup v. Krishna Murari Mangal, (2010) 14 SCC 266 | Reaffirmed the requirements of Section 63 of the Succession Act and Section 68 of the Evidence Act, stating that the testimony of a single attesting witness can be sufficient if it proves all necessary elements of execution.73 |

| In The Goods of Saroj Kumar Chatterjee, APD No. 7 of 2021 (Cal HC) | A recent Calcutta High Court ruling emphasizing that direct evidence of attesting witnesses holds greater evidentiary value than the opinion of a handwriting expert, especially when there are no substantial suspicious circumstances.55 |

| John Vallamattom v. Union of India, (2003) 6 SCC 611 | Struck down Section 118 of the Indian Succession Act (restricting charitable bequests by Christians) as unconstitutional, upholding testamentary freedom.87 |

| Mary Roy v. State of Kerala, (1986) 2 SCC 209 | A landmark succession case that, while not directly on probate, established the applicability of the Indian Succession Act to Travancore Christians, fundamentally altering inheritance rights.87 |

| Benga Behera v. Jagat Kishore Acharya, AIR 1915 Cal 85 | An early Calcutta High Court judgment clarifying that merely being cited in a probate application does not make one a defendant; one must appear and oppose the grant.52 |

Part VI: Your Trusted Partner in Succession Matters

About Patra’s Law Chambers

Patra’s Law Chambers is a premier law firm based in the heart of Kolkata, specializing in the intricate fields of succession, testamentary, and property law. With decades of collective experience, our team of dedicated legal experts provides comprehensive solutions for Will drafting, estate planning, and navigating the complexities of probate and administration proceedings in the Calcutta High Court and district courts across West Bengal. Our mission is to safeguard your legacy and ensure a smooth, dignified transfer of assets to the next generation.

- Address: 12/3, Old Post Office Street, Kolkata – 700001, West Bengal, India.

- Contact: +91 98765 43210 | [email protected] | www.patraslawchambers.com

Call to Action

The process of obtaining probate can be daunting, particularly when faced with legal challenges or complex family dynamics. At Patra’s Law Chambers, we provide expert guidance and robust representation for all testamentary matters in West Bengal. Whether you are an executor seeking to probate a Will, a beneficiary protecting your inheritance, or an individual planning your estate, our team is here to assist you. Contact us today for a confidential consultation to secure your family’s future.

- Hashtags:#ProbateLawIndia #CalcuttaHighCourt #IndianSuccessionAct #ProbateKolkata #WillAndTestament #EstatePlanning #SuccessionLaw #LegalAdviceIndia #WestBengalLaw #PatrasLawChambers #TestamentarySuit #InheritanceLaw #ProbateProcess #ExecutorOfWill #LegalHeir #PropertyLaw #IndianLawyer #KolkataLawyer #HighCourtProcedure #LandmarkJudgments

- Resources: A Complete Guide to Probate Law in India & Procedures in Calcutta High Court (2025).pdf

-

Works cited

- org, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/339285/#:~:text=(h)%E2%80%9CWill%E2%80%9D%20means,into%20effect%20after%20his%20death.

- Testamentary Succession under Indian Succession Act – ezyLegal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.ezylegal.in/blogs/learn-everything-about-the-testamentary-succession-under-the-indian-succession-act-1925

- Will and Its Essentials | PDF | Will And Testament | Private Law – Scribd, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/787895598/WILL-AND-ITS-ESSENTIALS

- Types of Wills in India and Their Essential Features, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.ahlawatassociates.com/blog/types-of-wills-in-india

- THE CONCEPT OF WILL – JLRJS, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://jlrjs.com/the-concept-of-will/

- Get An overview of will under Indian Succession Act, 1925, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.indiafilings.com/learn/an-overview-of-will-under-indian-succession-act-1925/

- Indian Succession Act 1925 – Complete Bare Act – B&B Associates LLP, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://bnblegal.com/bareact/indian-succession-act-1925/

- chhotacfo.com, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.chhotacfo.com/blog/wills-in-india-importance-essentials-and-legal-requirements/#:~:text=REQUIREMENTS%20FOR%20A%20VALID%20WILL,capacity%20to%20make%20a%20will.

- Validity of a Will under Indian Law – Satsheel Gurugram Advocate, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.gurugramadvocate.com/validity-of-a-will-under-indian-law/

- Types of Will in India and Essential Elements of a Valid Will in India – Aditya & Co. Advocates, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://adityaandco.com/types-of-will-in-india/

- Wills In India: A Complete Guide For Non-Lawyers – Yellow, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.getyellow.in/resources/wills-in-india-a-complete-guide-for-non-lawyers

- Format Of A Will In India: A Guide To The Essentials – Yellow, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.getyellow.in/resources/format-of-a-will-in-india-a-guide-to-the-essentials

- s3waas.gov.in, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s32d579dc29360d8bbfbb4aa541de5afa9/uploads/2025/02/202502261846525733.pdf

- Probate Of a Will – ClearTax, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://cleartax.in/s/probate-of-a-will

- Probate under Indian Succession Act: Essential Guide to Will and Estate Planning – Corpotech Legal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://corpotechlegal.com/probate-under-indian-succession-act/

- Probate Process in India: When and Why is it Required? – S.S. Rana & Co., accessed on September 11, 2025, https://ssrana.in/articles/probate-process-in-india-when-and-why-is-it-required/

- Understanding Probate: What It Is And Why It Matters – Mitt Arv Blogs, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://blogs.mittarv.com/understanding-probate-what-and-why-it-matters/

- Useful Judgments (High Court) – West Bengal Judicial Academy, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/pages/view/147/132-useful-judgments-(high-court)

- Guide to Probate and Letter of Administration – PravasiTax, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://pravasitax.com/information-hub/tax/succession-planning/succession-planning-and-will/Guide-to-Probate-and-Letter-of-Administration

- Defining Probate, Letter of Administration and Succession Certificates through Legal Lenses – Lawyered, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.lawyered.in/legal-disrupt/articles/defining-probate-letter-administration-and-succession-certificates-through-legal-lenses/

- Obtaining A Letter Of Administration In India – Yellow, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.getyellow.in/resources/obtaining-a-letter-of-administration-in-india

- navigating the letter of administration : process in indian law – Legal Help NRI, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://legalhelpnri.com/navigating-the-letter-of-administration-process-in-indian-law/

- LETTER OF ADMINISTRATION – How To Obtain – Easy 5 Steps Guide | Shreeyansh Legal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.shreeyanshlegal.com/letter-of-administration/

- Calcutta High Court – Wikipedia, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calcutta_High_Court

- Matters at Hon’ble High Court: – A.L.L.O.W.B, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://allowb.org/assets/pdfs/courtmatters/fc2.pptx

- 2017 AIR CC 1678 (CAL) – AIROnline, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.aironline.in/legal-judgements/2017+AIR+CC+1678+%28CAL%29

- Prabir Kumar Das vs Smt. Jayanti Das And Anr. on 18 August, 2006, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/524019/

- Original jurisdiction of the High Courts in the presidency towns | Reform of Judicial Administration | Law Commission of India Reports – AdvocateKhoj, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/lawreports/reformofjudicial/18.php?Title=Reform%20of%20Judicial%20Administration

- Letters patent (calcutta hc) : Letters Patent Constituting the High …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/act/in/5a979dd64a93263ca60b74d6

- Why is a Letters Patent Appeal called so? – Law Stack Exchange, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://law.stackexchange.com/questions/86124/why-is-a-letters-patent-appeal-called-so

- The Calcutta High Court (Jurisdictional Limits) Act, 1919., accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/wbja_adm/files/The%20Calcutta%20High%20Court%20(Jurisdictional%20Limits)%20Act,%201919.pdf

- Section 300 – The Indian Succession Act – LAWGIST, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://lawgist.in/indian-succession-act/300

- section 300 indian succession act, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=+section+300+indian+succession+act

- Section 300 in The Indian Succession Act, 1925 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1725467/

- Section+300+of+Indian+Succession+Act | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/Section%2B300%2Bof%2BIndian%2BSuccession%2BAct

- Calcutta High Court Upholds ‘Legitimate Interest,’ Grants Caveatrix Time Extension Amid Procedural Dispute in Probate Case – 24Law, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://24law.in/story/calcutta-high-court-upholds-%E2%80%98legitimate-interest%E2%80%99-grants-caveatrix-time-extension-amid-procedural-dispute-in-probate-case

- Calcutta High Court (Original Side) Rules, 1914 Rule 28 – CourtKutchehry, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.courtkutchehry.com/Judgement/Search/AdvancedV2?s_acts=Calcutta%20High%20Court%20(Original%20Side)%20Rules,%201914§ion_art=rule&s_article_val=28

- original+side+rules+of+Calcutta+High+Court | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/original%2Bside%2Brules%2Bof%2BCalcutta%2BHigh%2BCourt

- Section 1st in The Rules of The High Court At Calcutta (Original Side …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/170187458/

- IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA CIVIL REVISIONAL JURISDICTION APPELLATE SIDE C.O. No. 136 of 2015 In the matter of – West Bengal Judicial Academy, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/wbja_adm/files/2016%20%281%29%20CLJ%20%28CAL%29%20408.pdf

- How to draft a probate petition – iPleaders, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://blog.ipleaders.in/draft-probate-petition/

- Probate of Will in Kolkata: Meaning, Process and Legal Insights, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.ezylegal.in/blogs/probate-of-will-in-kolkata

- PROBATE – DiL SE WiLL, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.dilsewill.com/probate

- Guide to Probate Application in India – ezyLegal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.ezylegal.in/blogs/what-is-a-probate-application-filing-process-cost-etc

- How to Obtain a Probate Certificate in Kolkata – ezyLegal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.ezylegal.in/blogs/how-to-obtain-a-probate-certificate-in-kolkata

- Apply For Probate Of Will In Kolkata – Lawtendo.com, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.lawtendo.com/legal-services/probate-of-will/kolkata

- The West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970 – West Bengal Judicial …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/wbja_adm/files/The%20West%20Bengal%20Court-Fees%20Act,%201970.pdf

- West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970 – Latest Laws, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.latestlaws.com/bare-acts/state-acts-rules/west-bengal-state-laws/west-bengal-court-fees-act-1970/

- West Bengal Court-Fees Act, 1970 | PDF | Leasehold Estate | Probate – Scribd, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/352954633/West-Bengal-Court-Fees-Act-1970

- IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION APPELLATE SIDE Present: Hon’ble Justice Nishita Mhatre, And Hon’b, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/wbja_adm/files/AIR%202015%20CALCUTTA%20150.pdf

- How to Publish a Probate Public Notice in a Newspaper – Column, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.column.us/resources/how-to-publish-a-probate-public-notice-in-a-newspaper/

- AIR 1915 CALCUTTA 85 – AIROnline, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.aironline.in/legal-judgements/AIR+1915+CALCUTTA+85

- For The vs Krishnaveni And Another) And Submitted … on 23 February, 2024, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/152502447/

- filing of caveat doctypes: kolkata – Calcutta High Court – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=filing%20of%20caveat%20%20doctypes%3A%20kolkata&pagenum=3

- Calcutta High Court Grants Probate for Disputed Will, Rules in Favor of Direct Evidence Over Expert Analysis – 24Law, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.24law.in/story/calcutta-high-court-grants-probate-for-disputed-will-rules-in-favor-of-direct-evidence-over-expert

- how to file probate doctypes: kolkata – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=how%20to%20file%20probate+doctypes:kolkata

- testamentary suit – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=testamentary%20suit

- Key Supreme Court Judgments on Wills : Testamentary Capacity, Suspicious Circumstances & Probate in India – Rest The Case, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://restthecase.com/knowledge-bank/landmark-supreme-court-judgements-related-to-wills

- Venkatachala Iyengar v. B.N Thimmajamma And Others …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/h.-venkatachala-iyengar-v.-b.n-thimmajamma-and-others:-establishing-rigorous-standards-for-valid-execution-of-wills/view

- Venkatachala Iyengar vs B. N. Thimmajamma & Others on 13 November, 1958 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/22929/

- Burden of Proof in Will Validity: Insights from Smt Jaswant Kaur v …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/burden-of-proof-in-will-validity:-insights-from-smt-jaswant-kaur-v.-smt-amrit-kaur-and-others/view

- Establishing the Burden of Proof in Will Validation: Insights from …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/establishing-the-burden-of-proof-in-will-validation:-insights-from-ramchandra-rambux-v.-champabai-and-others/view

- law of evidence relating to witnesses to a will – BCAJ | Bombay Chartered Accountant Journal, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://bcajonline.org/journal/law-of-evidence-relating-to-witnesses-to-a-will/

- Pulak Mukherjee Santosh Mukherjee & Ors., accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.wbja.nic.in/wbja_adm/files/Title-3%20Also%20available%20at%202015%20(3)%20CLJ%20(Cal)%20222_1.pdf

- REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO(S) 13192 OF 2024 (Arising out of Special L, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/27882/27882_2018_17_1503_58238_Judgement_02-Jan-2025.pdf

- Explained: Supreme Court on Suspicious circumstances in a WILL – AasaanWill, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.aasaanwill.com/blog-posts/explained-supreme-court-on-suspicious-circumstances-in-a-will

- Gorantla Thataiah vs Thotakura Venkata Subbaiah & Ors on 19 March, 1968 – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1107638/

- suspicious circumstances in the will – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=suspicious%20circumstances%20in%20the%20will

- Supreme Court Strikes Down Suspicious Will: Widows Rights Triumph Over Nephews Claims in Landmark Inheritance Battle – Edu Law, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.theedulaw.in/content/judgements/165/Supreme-Court-Strikes-Down-Suspicious-Will:-Widows-Rights-Triumph-Over-Nephews-Claims-in-Landmark-Inheritance-Battle

- will+suspicious+circumstances | Indian Case Law – CaseMine, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/search/in/will%2Bsuspicious%2Bcircumstances

- testamentary capacity in wills – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=testamentary%20capacity%20in%20wills

- Testamentary Capacity and Burden of Proof in Will Validation …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/testamentary-capacity-and-burden-of-proof-in-will-validation:-gorantla-thataiah-v.-thotakura-venkata-subbaiah-and-others/view

- Gopal Swaroop v. Krishna Murari Mangal & Ors. (2010 INSC 817 …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/gopal-swaroop-v.-krishna-murari-mangal-&-ors.-(2010-insc-817):-upholding-the-sanctity-of-will-execution-in-joint-family-property-disputes/view

- Shashi Kumar Banerjee v. Subodh Kumar Banerjee: Reinforcing the …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/shashi-kumar-banerjee-v.-subodh-kumar-banerjee:-reinforcing-the-primacy-of-intrinsic-evidence-in-probate-of-holograph-wills/view

- Proving of a Will: Suspicious Circumstances and the Limited Impact …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/proving-of-a-will:-suspicious-circumstances-and-the-limited-impact-of-registration-%E2%80%93-rani-purnima-debi-v.-kumar-khagendra-narayan-deb/view

- Balwant Rai Kumar vs Smt. Amrit Kaur – CourtKutchehry, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.courtkutchehry.com/Judgement/Search/t/384427-balwant-rai-kumar-vs-smt

- RABINDRA NATH MUKHERJEE Vs. PANCHANAN BANERJEE – REGENT COMPUTRONICS PVT. LTD., accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.the-laws.com/encyclopedia/browse/case?caseId=415991429000&title=rabindra-nath-mukherjee-vs-panchanan-banerjee

- Legal Principles on Proving the Genuineness of a Will: Commentary …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/legal-principles-on-proving-the-genuineness-of-a-will:-commentary-on-sushila-devi-v.-pandit-krishna-kumar-missir-and-others/view

- Madhukar D. Shende v. Tarabai Aba Shedage: Upholding …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/madhukar-d.-shende-v.-tarabai-aba-shedage:-upholding-testamentary-capacity-and-res-judicata-in-property-disputes/view

- Supreme Court (SC) Judgements on Indian Succession Act, 1925 – Latest Laws, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.latestlaws.com/related-judgements/366/indian-succession-act-1925/

- Supreme Court Upholds Exclusive Authority of Probate Courts in …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/supreme-court-upholds-exclusive-authority-of-probate-courts-in-will-validation:-chiranjilal-shrilal-goenka-v.-jasjit-singh-and-others/view

- Chiranjilal Shrilal Goenka (Deceased) … vs Jasjit Singh And Ors on 18 March, 1993, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1878478/

- Limits on Revocation of Probate: Insights from Anil Behari Ghosh v …, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.casemine.com/commentary/in/limits-on-revocation-of-probate:-insights-from-anil-behari-ghosh-v.-smt-latika-bala-dassi-and-others/view

- ANIL BEHARI GHOSH Vs. LMFLCH BALA DASSI – The Laws, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://www.the-laws.com/encyclopedia/browse/case?caseId=005591240000&title=anil-behari-ghosh-vs-lmflch-bala-dassi

- citation in probate – Indian Kanoon, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=citation%20in%20probate

- GOPAL SWAROOP V KRISHNA MURARI MANGAL AND ORS – Bhartiya Legal Support Foundation – August 7, 2021, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://bhartiyafoundation.com/judgement/gopal-swaroop-v-krishna-murari-mangal-and-ors/

- indian succession act doctypes: judgments, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/search/?formInput=indian%20succession%20act+doctypes:judgments

- Raja Jagat Kishore Acharya Chaudhury vs Hemendra Kishore Acharya Choudhury And … on 3 August, 1934, accessed on September 11, 2025, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1203592/?type=print